What Can You Learn from David Mamet About Adding Subtext to Your Script?

Little-known indie filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock once famously said,"Drama is real life with all the boring parts cut out."

The fact is, in movies, a screenwriter's job is primarily to tell a story in pictures. And in order to prove my point, I'm going to focus on one of the most dialogue heavy films in recent memory, David Mamet's adaptation of his 1984 play, the Pulitzer-Prize winning Glengarry Glen Ross.

An extension of this dictum should then be: in movies, as in all good drama, no one says what they want, or, more charitably, they are at least as prevaricating as the average Joe or Jane. Because, just like in life, dialogue (or conversation, depending on what plane of reality you happen to be inhabiting) is all in the subtext, the hidden motivations and secret engines that drive our interactions.

"If a writer of prose knows enough about what he is writing about, he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. -- Ernest Hemingway”

But, to put it bluntly, some writers just can't help having their characters say what they mean (and the movie business isn't, you know, the truthiest). And gosh bless 'em, they turn out screenplays by the forest, screenplays that sometimes get made into movies.

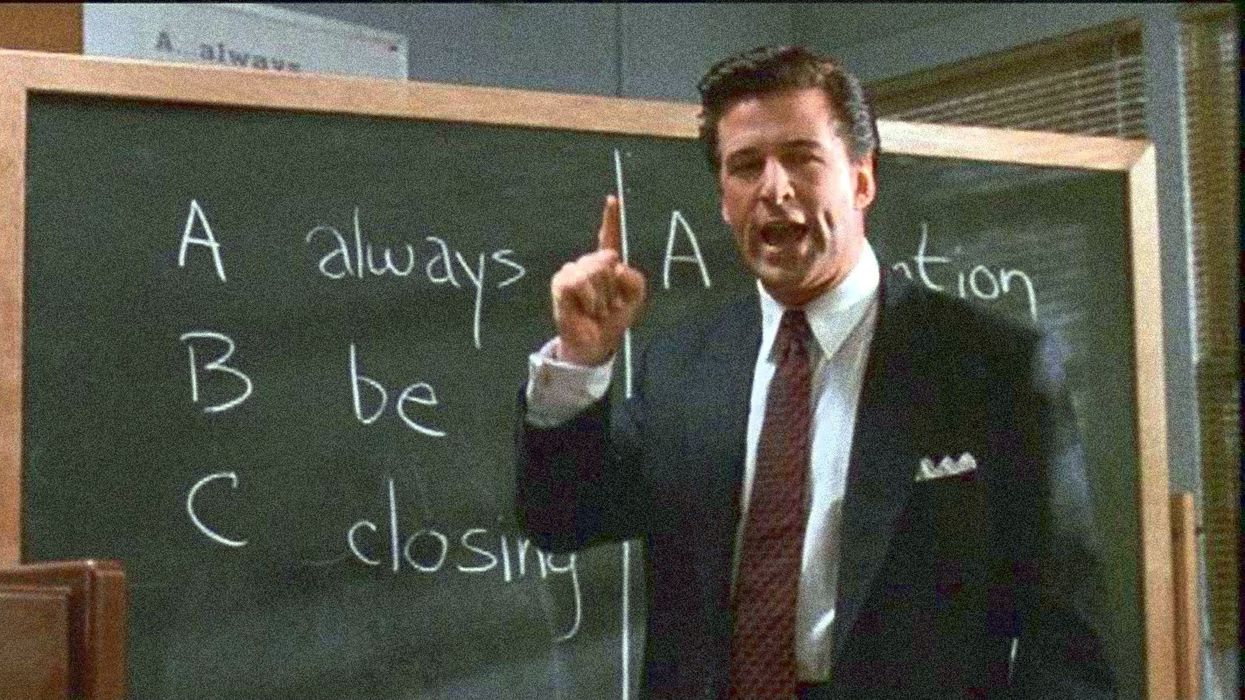

Mamet's plays and films (and TV shows) have brought a unique take on the American vernacular to audiences for going on five decades. In his work, when a character speaks, you better believe it's necessary. And no one says what they mean. Even in Alec Baldwin's famous scene from Glengarry Glen Ross, the issue isn't steak knives. And it's not just Alec Baldwin's (nameless, except for a NSFW sobriquet) character's motivation that provokes his unforgettable monologue. His superficial motivation would be his favor to Mitch and Murray, the bosses at the real estate company for whom he is doing a favor by lighting a fire under an underperforming, sad-sack sales team.

(Note: In case you've never had the pleasure of basking in the gleeful tirade below, it's super NSFW, depending on where you work.)

And yet, and I hate to say it -- and usually run screaming from the room when someone does, but it's more complex than that. Characters do not eat by motivation alone. On any given day, we are buffeted by the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune that assailed Shakespeare's prince, from the alarm clock that fails to go off, the lack of hot water in our shower, the missed bus/train/unforeseen traffic jam/headache/cheating spouse/etcetera. What we say and do are frequently not only diametrically opposed, but, ironically, the sum of what has happened to us throughout the course of the day, and by extension, our lives. Cosmic, no?

In those few minutes, Baldwin's character, who has driven there in an "$80,000" car to berate the sales staff, isn't delivering a pep-talk; he's not even haranguing these poor schnooks. In the nameless salesman's eyes, he's there on a "mission of mercy." On some level, he truly wants to help these men, each of whom, in their own way, has fallen into the desuetude of just scraping by. He's looking down from Mount Olympus, here on a rainy night to give these guys some "tough love." And each character in that office is the product of the days and years that have brought them to that moment, though Mamet has been quoted as saying, in an excellent interview with The Paris Review, that he doesn't care about anything except the question,

"Does the character need to convey that information? If the answer is no, then you’d better cut it out, because you aren’t putting the audience in the same position with the protagonist -- I try to adopt that as an absolute tenet. I mean, if I’m not writing for the audience, if I’m not writing to make it easier for them, then who the hell am I doing it for? And the way you make it easier is by following those tenets: cutting, building to a climax, leaving out exposition, and always progressing toward the single goal of the protagonist. They’re very stringent rules, but they are, in my estimation and experience, what makes it easier for the audience."

And, most importantly:

"People only speak to get something. If I say, Let me tell you a few things about myself, already your defenses go up; you go, Look, I wonder what he wants from me, because no one ever speaks except to obtain an objective. That’s the only reason anyone ever opens their mouth, onstage or offstage. They may use a language that seems revealing, but if so, it’s just coincidence, because what they’re trying to do is accomplish an objective."

Well, that's all very well and good, but how does this help me, you might be asking? And in doing so, you're illustrating his (and by extension, my) point: all actions are undertaken to accomplish an objective. A few general rules, courtesy of Mr. Mamet:

1. It's not what they say, it's what they do: "A character can swear up and down that they're 'an honest man,' but it's their actions that define them."

2. Never forget the audience: "And the way you make it easier is by following those tenets: cutting, building to a climax, leaving out exposition, and always progressing toward the single goal of the protagonist."

3. Let the dialogue speak for itself: "When you write stage directions -- unless they’re absolutely essential for the understanding of the action of the play (He leaves. She shoots him.) -- something else is going to happen when the actors and directors get them [on the set]."

And a few more (not from Mamet, but insightful), courtesy of a great article on the film over at Script Shadow:

4. Don't talk unless absolutely necessary – "Without question, one of the biggest mistakes I see from amateurs is characters who are only talking because they’re in a scene. If characters are only talking because a writer’s making them, the scene will be maddeningly boring."

5. Lying is good (for drama!) – Dialogue is always interesting when someone’s lying. Why? There’s a natural inclination for us readers to find out if the other party’s going to figure it out or not. Glengarry is one big lying fest. Shelley’s lying to all the leads about how they “won” a contest. Roma (Pacino) spends the entire movie lying to his mark. Ross (Ed Harris) and Aaronow (Alan Arkin) are lying about robbing the place. When a character has something to hide, the dialogue always has an extra spark to it.

And, last but most certainly not least:

6. CONFLICT! – "I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. One of the easiest ways to create good dialogue is through conflict. In almost every single scene in Glengarry Glen Ross, one character wants something while the other character wants something else."

Source: Script Shadow