Check Out New BBC Doc on Infamous Lost Jerry Lewis Film 'The Day the Clown Cried'

Today, it's a strange concept for some people (almost all of them born during the mid-90s and after) that there is such a thing as a "lost" movie; after all, what about YouTube?

But not only have some films/albums/books never been digitized, some movies are "lost" because they aren't supposed to be found. Such is the case with Jerry Lewis's famously unreleased film, The Day the Clown Cried. A new BBC Documentary, though, sheds light on this legendary film with information and production stills, and we've got it for you.

In the early 1970s, at the height of his power, the wildly successful and iconic comedian decided to write and direct a film that wouldn't be a comedy at all, but would take on the grave, almost unspeakably serious events of the Holocaust, arguably the largest tragedy in human history, an event that saw the extermination of roughly 11 million people, 6 million of them Jews, along with other so-called "undesirables," including Communists, Slavic peoples, the Romani, homosexuals, conscientious objectors, Jehovah's Witnesses, those with physical and mental traits deemed unworthy, and anyone else Hitler viewed as "impure".

Though Alfred Hitchcock, among others, had worked on a rarely-seen British documentary shot at the end of WWII, the first dramatic film released in the US that dealt with the crimes of Nazi Germany from the point of view of a survivor wasSidney Lumet's The Pawnbroker, in 1964; the horror of the subject was seen as too sensitive for American audiences, and it wasn't until the most commercially successful director in Hollywood at the time, Steven Spielberg, released Schindler's List in 1993 that the true horror of the concentration camps could be explored in a Hollywood movie.

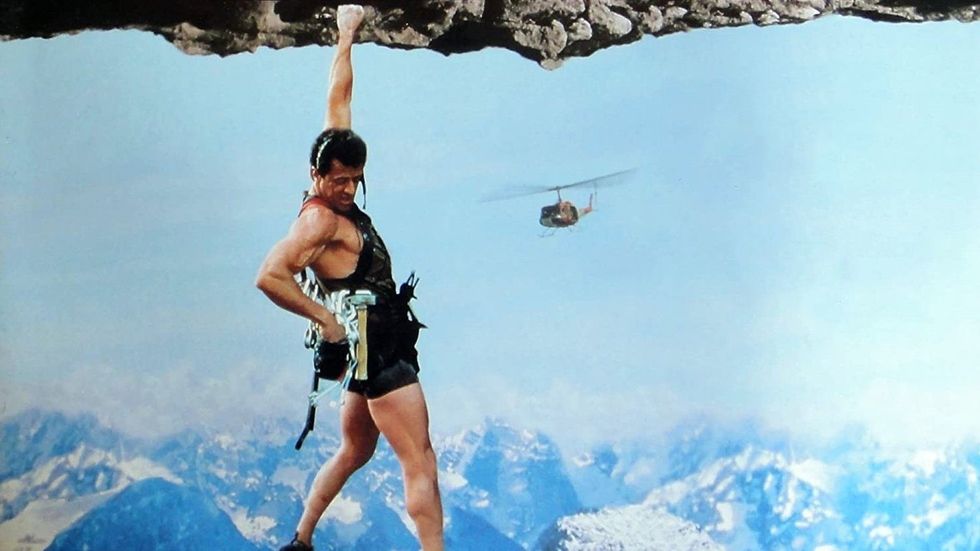

But the idea that Jerry Lewis, the "Nutty Professor," would go where few would tread (even Kubrick's film on the subject, the Aryan Papers, was never made) was almost unthinkable. Shot largely in Sweden, the film's plot concerns Lewis' titular clown, a gentile who is sent to a political prisoner's camp for anti-Hitler statements; he attracts the attention and admiration of Jewish children, who see him through barbed wire, and is eventually sent to Auschwitz, used by the Nazis (who always attempted, with varying success, to keep their atrocities out of sight) as a way to quiet the children and maintain order. That summary of the film bears a passing similarity to Life is Beautiful, yet while the latter film would go on to great acclaim and awards, Lewis hid his away, though some making-of footage has surfaced, and the script has been available for some time.

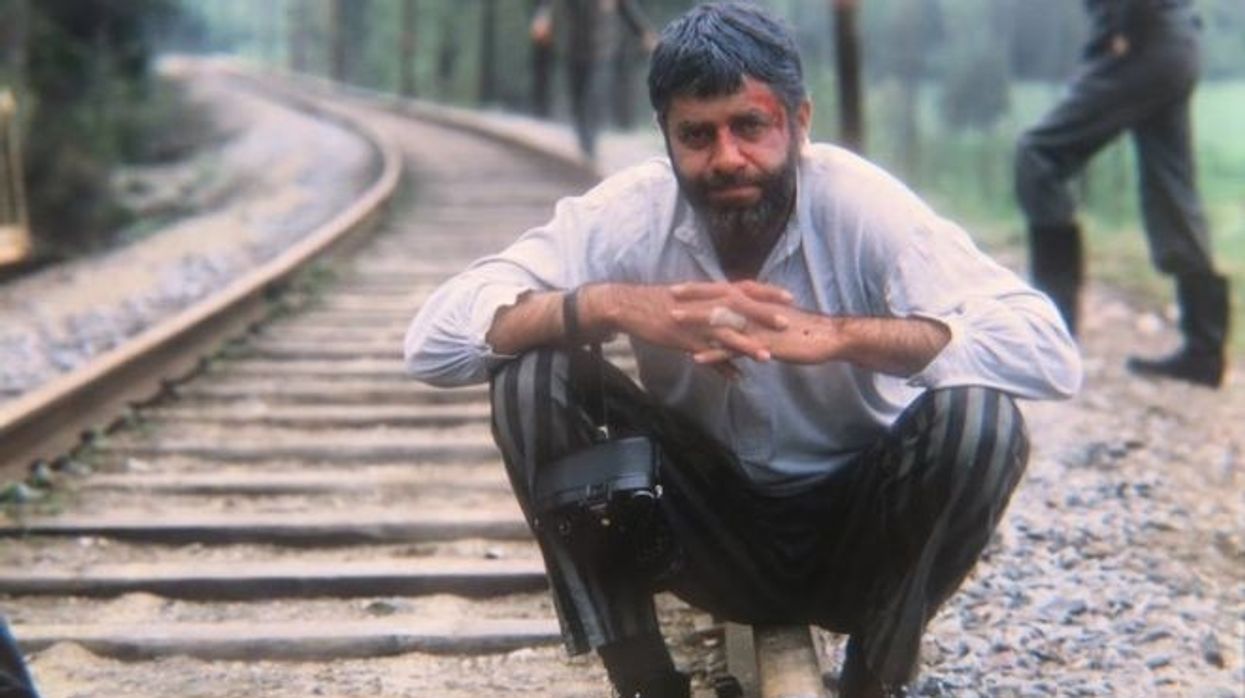

A 1992 article from Spy magazine reports that though Lewis initially balked at the script, he later decided that it was his duty to tell the story of a clown, forced to act as a pied piper of sorts by the genocidal camp leaders, leading unwitting children to their doom. Lewis was intensely serious about his work: he went on a diet for the role, toured the camps where so many lives had been lost, and assembled a cast including Harriet Andersson, who had been directed by Ingmar Bergman in Smiles of a Summer Night. The film was shot mainly in Paris and Sweden and, after financing fell through during production, owing to a feud with his producer, Lewis, who did not even own the option to the script anymore, sank his own money into the film, obsessed by the project. In this video, he is seen in Paris during pre-production.

And when all was said and done, nothing really happened to this film. It had been too personal of an obsession, it seems, for Lewis, who once remarked, "You will never see it. No one will ever see it, because I am embarrassed at the poor work."

The film's negative has been held for years by the Swedish studio where it was made, while the screenwriters have squashed any attempts to make a deal around their work, and a rough cut on VHS, kept in a briefcase in Lewis's office, has been the only copy, screened rarely over the years for colleagues and a few journalists. Harry Shearer, a key utility player on The Simpsons, as well as a member of Spinal Tapand long-time member of Christopher Guest's ensemble, is one of the few to have seen the film and famously remarked to Spy:

This was a perfect object. This movie is so drastically wrong, its pathos and its comedy are so wildly misplaced, that you could not, in your fantasy of what it might be like, improve on what it really is. "Oh, my God!" — that’s all you can say.

Though a comic legend, philanthropist, and truly innovative cinematic talent, Jerry Lewis has always had a famously rocky relationship with his place in the world of culture. A respected artist in many countries, including, notably, France, whose own Jean-Luc Godard has opined:

Jerry Lewis is the only American director who has made progressive films. He was much better than Chaplin and Keaton. He could have made marvelous movies, but he won’t now… because of the time in which he is living. If he had lived during the October Revolution, he might have made a magnificent movie,"

Lewis's oft-forgotten work with Martin Scorsese in The King of Comedy also testifies to his seriousness as an artist, and if The Day the Clown Cried can teach anyone anything, perhaps it's that sometimes the real world outstrips art's ability to interpret that world, and our most passionate obsessions can quickly become follies without the cool hand of objectivity. Regardless, this is a fascinating look at a failed work, and it's arguable that failures, even more than successes, are where our best lessons are learned.

Source: BBC