Watch: What Spike Lee's 'Do the Right Thing' Can Teach You about Editing

True enough: there are few directors who mix cantankerousness and raw brilliance the way Spike Lee does. Also true: much of his genius is in the editing.

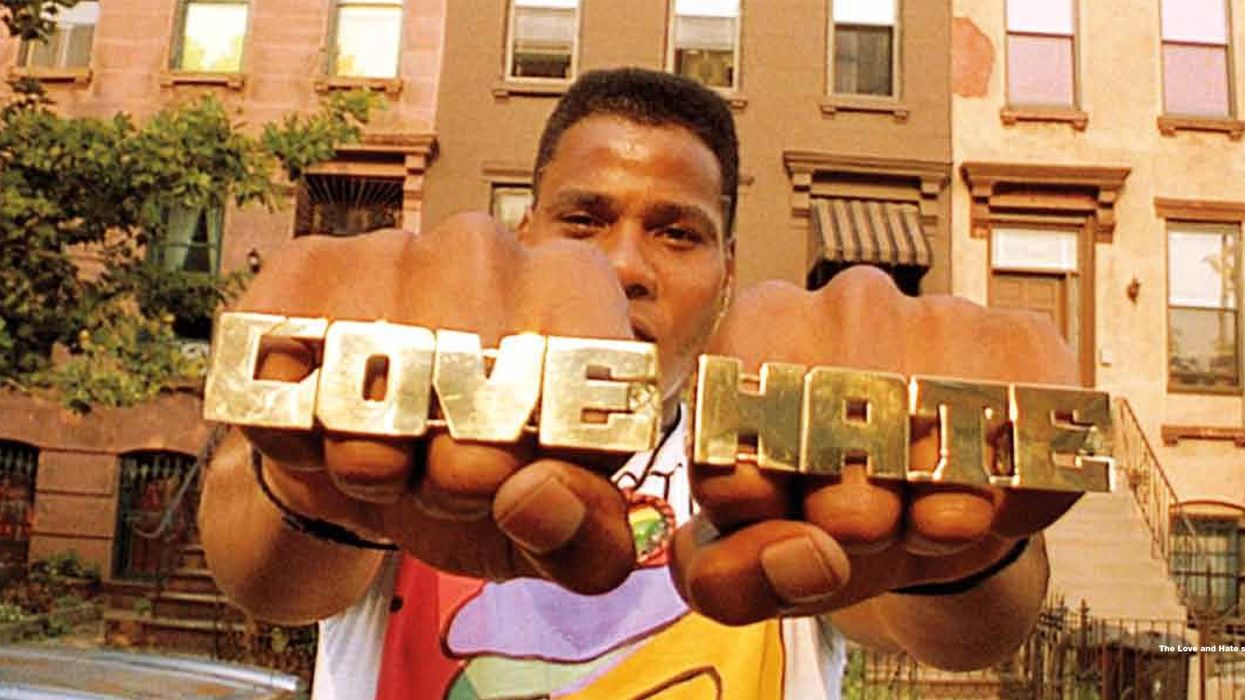

"Let the camera tell the story" might be a platitude that some directors aspire to but never reach, but Spike Lee reaches it in film after film. His seminal, angering, unsettling, and timeless film Do the Right Thing, about stormy and explosive race relations in the Brooklyn, NY summer heat, is no exception. This excellent video essay by Nick Coleman takes us through the movie a bit to show which editing tools Lee uses to tell his story, and how he's using them. Below are a few techniques that stood out to us.

Transitions

It is important to remember that the cinematography decides how quickly, how slowly, how smoothly, or how disjunctively a viewer moves through a film. Coleman uses the opening scene of the film as an example. We are treated first to the verbal fireworks (That's the truth, Ruth!) of Samuel L. Jackson's Mister Senor Love Daddy; his voice, and his general personal mood, will carry us into the narrative of the movie, along with the camera, which first takes us to the bed of Ossie Davis' (Da) Mayor, who will be a major character in the film. This sequence foreshadows the structure of the rest of the film, in which radio monologues (and music) wipe away one scene and set up another.

Continuity

When Lee uses the radio as a throughline in his film, he is establishing continuity: he's creating a device by which viewers can recognize that they've moved from one part of a story to another, and also recognize that they're moving through a narrative, with specific plot points. He does this visually as well: when the camera moves away from Love Daddy's radio studio to the apartment of Ossie Davis' character, Coleman marvels, and rightfully so, at the smooth way in which Lee subliminally compares the two places and tells moviegoers that the two spaces he's filming will turn out to be very significant. Lee also uses what Coleman calls "a reestablishing shot," going from one character to another by backing away from one face and zooming in on the other. This could also be called "match on action," meaning that one movement the camera makes mimics the movement that proceeds it.

We should think about what the analytical ramifications of each transition might be.

Avoiding cheat cuts

Coleman swerves a little from the film at hand to address ways in which transition and continuity can be mishandled. He uses Michael Bay's Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen as an example: we should not, per Coleman, simply mimic a camera movement from one scene to another, for the "flow" of a film. Bay does this often, setting the stage for a general lack of articulation. We should instead think about what the analytical ramifications of each transition might be; as we weigh these things, a film can become more powerful. He does praise Bay's use of cross-cutting—in this case cuts from the earth to the sky with little warning—yet another technique, like close-ups or zoom-outs, to mainline the story, or its crucial elements, to readers' brains. If effectively used, as it is here, it has tremendous communicative potential.

Any thoughts about the editing in Do the Right Thing or Lee's other films? Let us know in the comments!

![Ethos, Pathos, Logos: 20 Effective Ways to Advertise [Infographic]](https://nofilmschool.com/media-library/ethos-pathos-logos-20-effective-ways-to-advertise-infographic.jpg?id=34064614&width=600&height=600&quality=90&coordinates=560%2C0%2C0%2C0)