'Spettacolo': SXSW Stranger-Than-Fiction Documentarians on Why Art Makes Life Worth Living

Jeff Malmberg and Chris Shellen's 'Spettacolo' is an elegiac testament to the power of art.

Of all the virtues of art, perhaps the least celebrated is its ability to provide catharsis. In his 2010 Spirit Award-winning documentary Marwencol, Jeff Malmberg told the story of a veteran who returned home only to suffer a brutal attack at a local bar. He processes the trauma of the assault, which left him with severe brain damage, by building a miniature fictional town in his backyard in which he enacts complex theatrical narratives. Malmberg is at SXSW 2017 with Spettacolo, another documentary that examines art's therapeutic capacity. But this time, it's not just one man—it's an entire village.

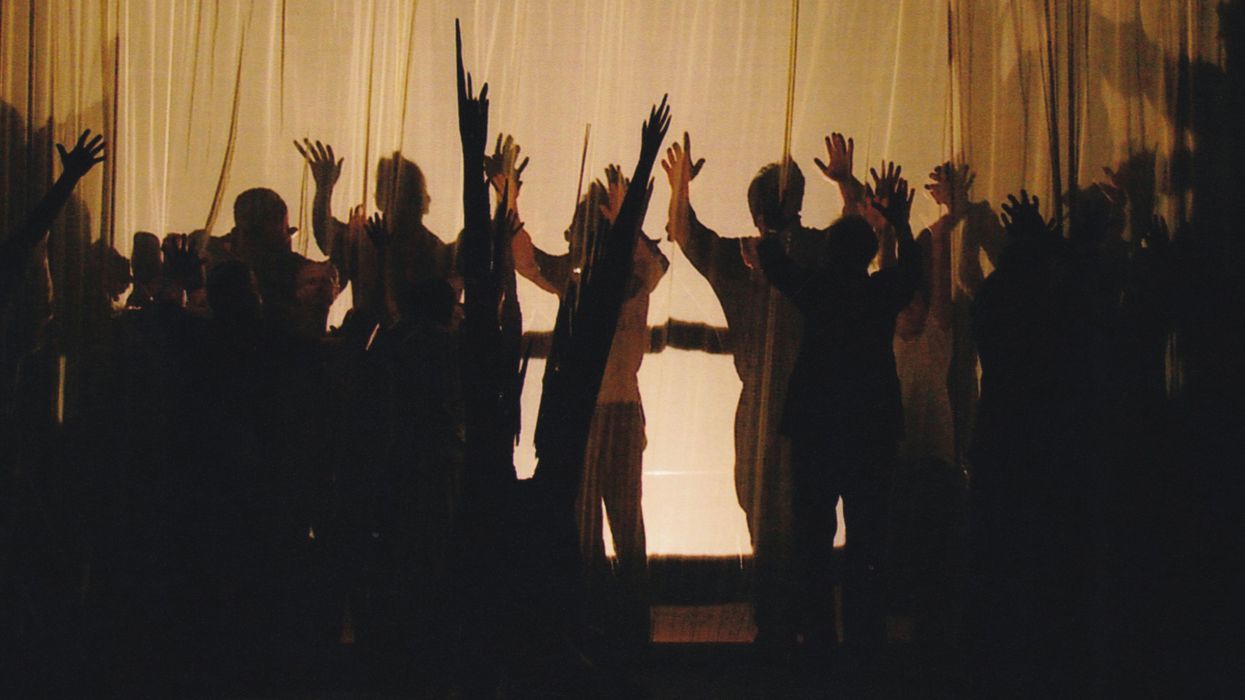

Monticcello, Tuscany. Population 136. Every year for 50 years, the entire town participates in an elaborate theatrical performance. Past topics: the town's near-annihilation at the hands of Nazis in WWII; the avarice of tourism, which has turned nearby buildings of historical significance into summer villas for the wealthy. The town's auto drama, or self-produced theater, gives villagers a platform on which to discuss pertinent social issues and honor their heritage. It also promotes community.

But in Italy's struggling economy, the town has fallen on hard times. Fewer and fewer residents are interested in devoting their hard-earned free time to theatrics; the younger generation, who in years past lent vital energy to the productions, is interested in leaving Monticcello altogether. It seems that only Andrea Cresti, the theater's de facto director, is fully invested.

That's why this year's topic is the end of the world.

No Film School caught up with directors Malmberg and Chris Shellen at SXSW 2017 to discuss their decision to embed themselves in the town of Monticcello, the film's stranger-than-fiction dramatic turns, the pivotal role of art in the modern world, and more.

No Film School: I was in Monticcello two summers ago. I had no idea the town had such a rich history of theater. How did you discover it?

Jeff Malmberg: As a tourist. I don't know if you were there for the same reason, but they have an amazing restaurant, La Porta. We were 10 minutes early for dinner and we just wandered around this town. It didn't seem like the other Tuscan towns—it wasn't hollowed out with wine and cheese shops. It seemed occupied by people. There was one open door—Andrea's [the main character]—and he was furiously scribbling. We were like, "Who is this guy, and what's going on?"

As a tourist, you snap these pictures, and you tell yourself these stories, but you never actually sit around to get the quotes. You're allowing the people in the town to be your extras in a tourist narrative.

Spettacolo has been this four- or five-year attempt to stop seeing that place as a tourist and start seeing it from the inside, from the point of view of the people.

NFS: Eventually, you moved to Monticcello to make the movie. What happened in between that first visit and the move?

Chris Shellen: We were finishing Marwencol at the time, so we took a year or two off to finish that. But [this idea] just kept sticking with us. Finally, we went back [to Monticcello] to go see the play just to see if it was worth filming, and it was amazing. So we decided to get our pitch together. We didn't speak Italian at the time, but we crafted together this translated pitch that we brought to them.

The villagers were very brave. They allowed two non-Italian speaking Americans to come and live with them and film them every day.

Malmberg: The first directorial decision was to move into the center of that town. And you know how small that town is. We stayed in the center of the town for six months, put the camera by the door, got coffee every morning, and just started talking to people. That became the directorial style—to embed. In that town, there are 30 people that talk to each other all day long, gossiping, so we got to be part of that.

Shellen:The news had covered [Monticcello] quite a bit, so [the villagers] were used to doing a certain song and dance for them, and they had their pattern down like we all do with our projects. So we had to stay past that, until that had worn off and they became themselves with us.

NFS: Were the villagers reluctant to trust you because they thought that you were making the regular news segment?

Shellen: Yes. They had told us that it takes a while for Tuscans to become real friends with people. They are very nice to everyone who visits them, but they consider friendship to be something special that you have to invest time in.

Malmberg: And it's a town of actors, so to speak. So they felt free to perform for you, but I don't think they believed in what we were doing. The last film we did, Marwencol, is about similar things, so we translated that into Italian and played that for them in their little theater and talked to them about it. I noticed a change in shooting the next day. It was like, "Oh, I see what you're after—you're after something a little more poetic than what most people come here to talk about."

NFS: On this film, you worked together as co-directors, and you are married. How did that change the process?

Malmberg: This film is just a further articulation of what our relationship was on Marwencol—[Shellen] produced it. She literally wrote the book on it. I need someone to knock my head. So she would come in and play guest director. You really need two people to climb up that ladder. Hopefully [Chris] and I learned stuff about collaboration on this film.

Shellen: Every project is an adventure.

Malmberg: What's that quote you always throw out?

Shellen: I love it. Pennebaker. Every time they go on set they fall in love again, and then every time they get into the editing suite they get a divorce.

NFS: How was this experience different from Marwencol in other ways?

Malmberg: I think of them as a good double feature: Marwencol first, and this second. The beginning of art and the possible end of art. And in the middle, what art can do for you.

The places where it was the same was getting to know someone and walking down a path with a subject. The great thing about working on a documentary for a really long time is that you get to live with someone. It's a collaboration [that spans] years.

"The nice thing about documentary—it makes you be quiet. It makes you listen. It makes you pay attention in a way that maybe don't do as well in real life."

I think documentaries are most interesting when you get to sit at the crossroads, so to speak, with the subject. There's no faking that. If you get to witness that as a filmmaker, and then play that back for the audience and then they get to participate in that, it's kind of tough to beat. And I think that's where documentary can sometimes beat narrative. To watch someone wrestle with decisions is holy ground. That, to me, was where it was similar to Marwencol.

Where it was different was that Spettacolo was 50 people. We were doing a portrait of a town. Andrea is obviously the center of that portrait, but you're still trying to represent a lot of people.

Shellen: In Italian, a foreign language. Our translation plans fell through a few weeks into shooting, so we realized we had to learn [Italian] really quickly.

NFS: When these decisions are being wrestled with—when your subject is at a crossroads—what is your approach as a documentarian? Do you step back and let events unfold? Do you ask a lot of questions?

Malmberg: It depends. We had less advantage with language this time. In Marwencol, some of the best conversations we had were off-camera. Spettacolo was definitely a chance to step back a little bit more. I think that's the nice thing about documentary—it makes you be quiet. It makes you listen. It makes you pay attention in a way that maybe we don't do as well in real life.

So, with the language [barrier], I think it created something a little more formalistic and distant, but [it] also [provided] a chance to observe and analyze later.

NFS: Halfway through the film, an unfortunate event happens. But it's incredible from a documentarian's perspective, because it perfectly suits the themes of the film and throws a monkey wrench into the narrative in a way that gets us closer to the truth. Let's call it the "bank event." When something like that happens, how, if it all, do you switch gears?

Shellen: What we do when we're in that situation is to take a look at what the story is, where our North Star is. We knew the film had to be about the theater, about the town and those people, so when things like the banking situation happened, we just dove into it. There were other things that happened in town that were really interesting but outside of that frame, and as much as you want to follow up on every interesting thing, you really have to keep your focus on what the story is.

Malmberg: It's always different: what you think the film and subject will be versus what the film and subject [actually winds up being]. So when the bank thing happened, or Georgio leaves [the theater].... he was one of our main characters. People said, "Oh, Georgio, he's the bright shining star. He's the one that shall represent the future of theater in Monticcello." So his leaving [the theater] was just as damaging to us, because we thought the character went away. But, of course, after a little red wine, you realize, "Oh, well, that's exactly the point, isn't it?"

"You actually kind of hope that your pre-existing ideas get blown out of the water."

So you actually kind of hope that your pre-existing ideas or questions get blown out of the water. When things like the bank thing happened, it was weird and kind of upsetting, but it's auto drama; in the end, you feel honored to be there and witness an example [of what you're making the movie about].

NFS: Did making this film change your perception of the inherent value of tradition?

Shellen: That's a good question. Yes, although I feel like now I've got sort of more of an Italian perspective on it, whereas before, I just wanted to protect it at all costs. But in this, Andrea has that wonderful line that he says toward the end: he thinks that, inevitably, the tradition will end, and that's probably a good thing that it ends before—

Malmberg: —its meaning is lost.

Shellen: Yeah, before it just becomes tradition for tradition's sake. I feel very mixed about it. I think it's both important to hang on to these things, because it is our past, but at the same time, maybe at some point, we need to let these things go.

Malmberg: That's a really good question because I think that actually gets at the root of what the film is about. It made me both appreciate [tradition] more and realize its cyclical nature. Of course, after 50 years in some place, someone like Georgio or a younger generation in Monticcello would just see [this theater] as grandpa's thing or dad's thing—as an obligation. And it made me understand that point of view. But it also made me understand what's worth protecting, and what's worth fighting for.

The great thing about documentaries is you don't have to answer the question as much as you have to raise it.

Shellen: In fact, it's better if you don't answer it.

NFS: The film definitely makes you think about your own relationship to tradition. I had a Bat Mitzvah and I hated it at the time, but now I look back on it fondly, like a torch that I carried.

Malmberg: Right. And I always wondered, with the villagers.... I mean, the way they talk about the past and the way they talk about their theater [made it seem as if] the past is kind of gilded. We tend to romanticize the past. They talk about [the theater] in the past so lovingly, and they complain it about it so much in the present. So where's the truth? I guess it's somewhere in the middle.

"Art is what makes life worth living—and even more so, it helps us live our lives."

Shellen: It's funny that you mentioned the Bat Mitzvah, because you're right—you have these frustrating experiences, and sometimes those wind up becoming our most precious memories. It definitely seemed that way for [the villagers]. The plays that were the biggest disasters for them—where the villagers rebelled against each other—were the ones that became their most precious memories.

Malmberg: As Andrea says in that opening scene, it kind of became one long play to them. They can't unpack it. It's just like this constant family album. [Making] this film has kind of allowed them to think about a tradition and whether it is worth fighting for. And I would bet that's why Andrea let us do it. He told me later that he wished [the villagers] appreciated the tradition a little bit more. And maybe watching the film has been a chance for them to think about whether it is worth continuing. It's a chance to reconsider the value of what they've been doing.

NFS: Clearly, you are both very interested in the idea of art as catharsis. Why do you find that compelling? Do you think it has a place in everyone's life?

Shellen: Art has a greater purpose and value than just something aesthetically pleasing. It can play a really vital role in our lives—in communication, in catharsis, in problem-solving, community-building. It has so many applications. Mark [in Marwencol] was using it to heal; this town was using it to build community and work through issues.

It's fundamental that we keep bringing up this quote that an Italian politician said. He was trying to work through these budget issues; they were slashing the Italian budget for the arts. And he said, "Well, you can't eat art." So, it's one of the first things to go.

NFS: It's so sad to think about someone saying that.

Shellen: It is sad. And we're seeing it here today with the threat. PBS, the NEH being threatened.

Malmberg: Yeah, I mean, our film was funded partly by the NEH. So it became ridiculously meta—we're making this film defending art that was supported by art that was being cut. In the film, Arturo says, "There's no more money for culture."

Shellen: There was also a quote that was inaccurately attributed to Churchill. Someone said, "We have to cut the arts budget because of the war," and he said, "Well, then what are we fighting for?" Art is what makes life worth living—and even more so, it helps us live our lives.

Malmberg: This film takes art outside of the abstract and makes it fundamental, makes it valuable.

Shellen: Art has literally kept Monticcello alive. In Tuscany, there are two types of towns: the big tourist towns, like Monticcello, and Pienza, which are largely tourist towns, and they're all focused on that. Then there are these ghost towns that are slowly drying up, and being bought by corporations and being turned into resort towns, where they have the locals still living there, but they're almost like actors in their own towns.

As the world speeds up, we're all victims of consumer mentality. As the towns were drying up, the villagers decided to create the theater almost as a way to just make their small voices heard. And they were. Because of that, people started coming to the town. They got a better road, they got some services. Theater literally saved their town.

For more, see our complete coverage of the 2017 SXSW Film Festival.

No Film School's coverage of the 2017 SXSW Film Festival is sponsored by Vimeo.