RIP Jonathan Demme, Humanist Horror Auteur-Turned Rock Doc Champion

Jonathan Demme, celebrated director of Silence of the Lambs, Philadelphia, and the indie hit Rachel Getting Married, died yesterday at the age of 73.

He got a horror film a Best Picture Oscar. He made the best concert documentary of all time. He introduced most of the world to Ray Liotta, Spalding Gray, Jeff Daniels, Anthony Hopkins, Anne Hathaway, Tom Hanks, Robin Hitchcock, Oprah, and Justin Timberlake. He's been called the great humanist of motion pictures, and that's true—but just as important as his empathy is his ability to dive headfirst into the darkest corners of humanity with a flashlight, trying to make us understand real suffering, anger, confusion, and loss.

His name was Jonathan Demme and he was 73 years old when he died today. Those of us lucky enough to be touched by his work will never forget him and his magnificent art, spanning 50 years of cinema from every genre under the sun.

Demme used the close-up like no other American filmmaker—as a site of confession, with characters looking directly at the audience, erasing our distance from them.

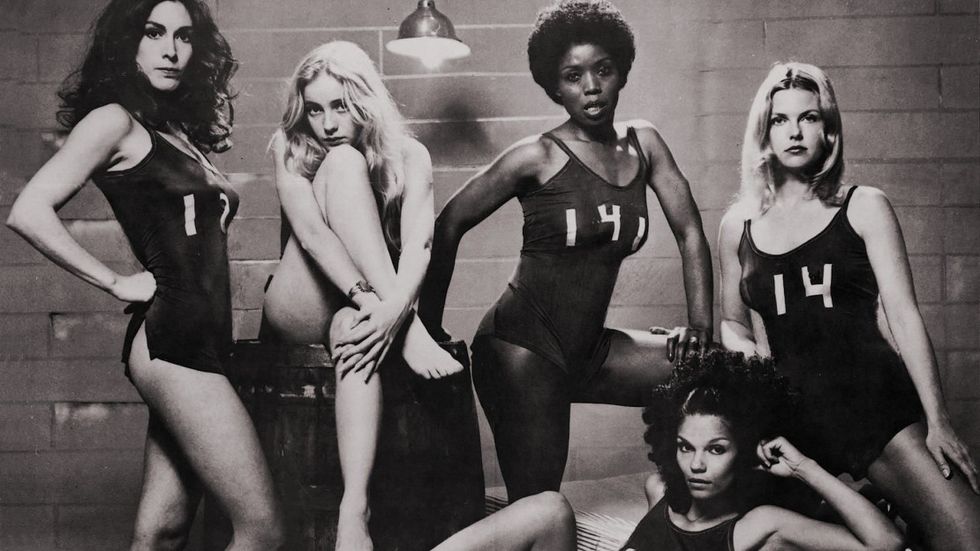

Demme's first film credits were as a publicist and a music coordinator. Like Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Ron Howard, Demme kickstarted his career as a grunt in the Roger Corman hired gun army. He wrote a number of the engineer/producer's Filipino exploitation films, making his first mark (with co-scenarist Joe Viola) on the delightfully bawdy and politically charged Black Mama, White Mama, which recasts The Defiant Ones as a woman-in-prison-romp, starring Pam Grier and Margaret Markov. It was the first taste of the maximalist fun Demme could bring to a simple idea. The film flirts with revolutionary violence, trying to weigh the human cost of an uprising versus personal freedom.

His first film as a director, the Corman-produced women-in-prison nightmare Caged Heat showed that Demme was serious about depicting misery. In the film, a bunch of gals plan a prison escape to flee their deranged matron, Barbara Steele. Demme became famous for making these kinds of casting choices—reframing beloved icons to show off their hidden strengths and letting them have fun in roles they wouldn't have been given otherwise. The film's slow build lets us sink into the mire of prison life, aided by former Velvet Underground member John Cale's angry score, which ends with an excruciating round of electroshock therapy sessions for our heroes. Caged Heat also features a prison drag show—one of the first instances of Demme's lifelong fascination with the act of performance.

Following Caged Heat was Crazy Mama, the first film set in what most fans would recognize as the Demme-verse. The soundtrack shouts one over-the-top novelty hit after another while a beautifully unhinged Cloris Leachman goes on a crime spree with a band of goofy outsiders across America. Leachman's Melba was the first of Demme's troubled but strong female leads, undeterred by the hand dealt to her by society. Melba would cut a hole in its fabric is she had to, every song on the radio acting as a Greek chorus to her exploits. Demme flipped the gender dynamic again in the following year's Fighting Mad, starring Peter Fonda as a farmer out to stop land developers from taking what belongs to him and his neighbors.

The revolutionary behind Black Mama, White Mama put his money where his mouth was time and again. He publicly campaigned against apartheid, gave voices to critics of oppression, and as late as last year missed a retrospective screening of one of his films at Metrograph because he needed to get on a flight to march at Standing Rock.

Demme kowtowed to no one. Last Embrace, his bizarro Hitchcock riff starring Roy Scheider, may have been too arch and staccato for Americans to embrace (it sure didn't help Brian De Palma during this period). Swing Shift should have been Demme's big ticket break, but he fought with star Goldie Hawn during production and lost, disowning the film afterward. Melvin & Howard, between them, fared a little better. Paul Le Mat plays a hopeful fool who finds a craggy, wrecked Howard Hughes (played by craggy, wrecked Jason Robards) in the desert and gives him a ride back to civilization. It's a delightful road movie—one of Demme's specialties.

Demme's gift: we'd watch a neon world of song, dance, fun, and adventure whirl by on our trip to something ultimately hellacious.

The first film that seems like only Demme could have created was also a road movie, a pop-kitsch picaresque full of his favorite musicians and people. Sister Carol East, John Waters, The Feelies, Charles Napier, Tracey Walter, John Sayles, and Talking Heads percussionist Steve Scales are just a few of the people that Jeff Daniels runs into after falling in love at first sight with Lulu-wigged Melanie Griffith in Something Wild. The film presents the famous faces they pass as just part of the natural tapestry of Demme's world. The soundtrack is stacked with eclectic hits from international acts; every scene feels like it could be the reason he made the movie.

Something Wild is pure joy until the hideous clash between the three leads in Liota's prefab house at the very end, when things get horrifically real. That was another of Demme's gifts: we'd watch a neon world of song, dance, fun, and adventure whirl by on our trip to something ultimately hellacious, but we're grateful for the experience nonetheless. Something Wild is the ultimate film about realizing you only live once.

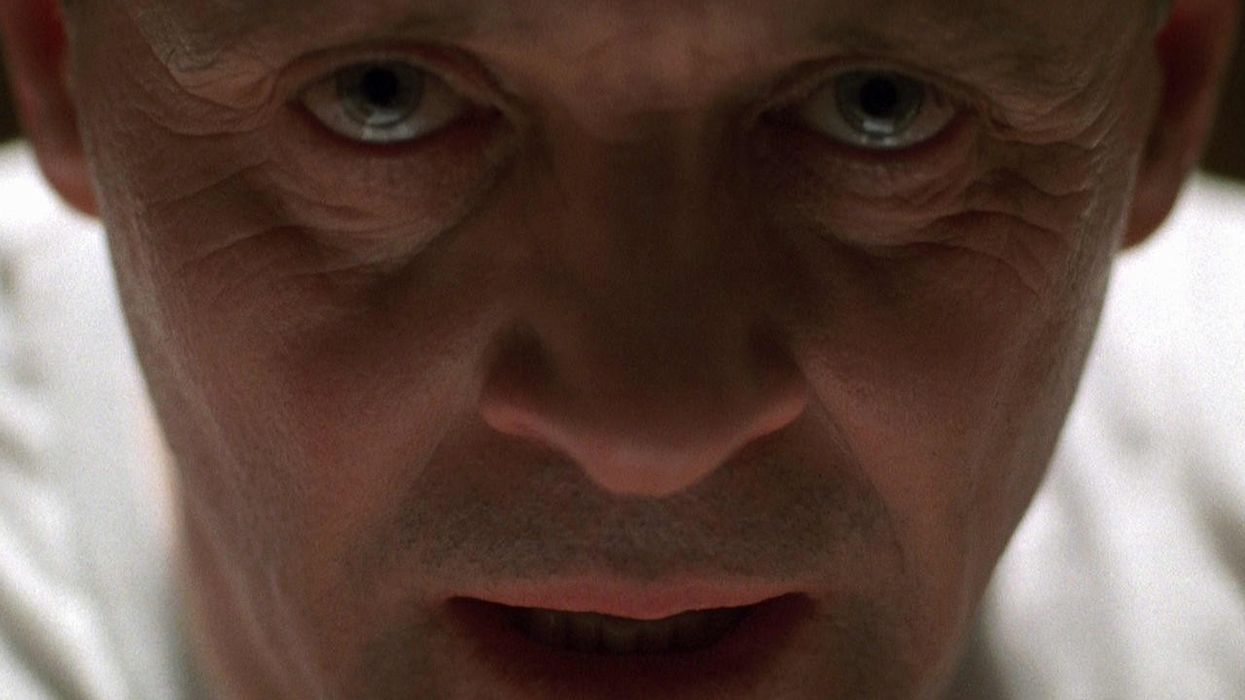

Each of Demme's movies, including his music videos, documentaries, shorts, and his work for TV (including one-of-a-kind oddity Who Am I This Time? for American Playhouse) is worth dissecting at length, but several seem to stick out above the others. There's the justifiably famous Silence of the Lambs, which is so jammed with great performances it's near impossible to pick a favorite. Demme here throws the full weight of his earnestness and sincerity behind Jodie Foster's diminutive FBI newbie, Clarice Starling. Her first big case happens to involve more red tape than she bargained for thanks to the involvement of a politician's missing daughter, and it also brings her face to face with Hannibal Lecter (a never more delectable Anthony Hopkins). Demme frames her surrounded by the towering men who control her and oppose her; Foster's performance, a thing of steely nonchalant beauty, exudes pure power. One of the film's most striking images is that of Starling flanked in an elevator by a half-dozen agents, all taller than her by at least two heads. Demme doesn't need to say a word about sexism; that image says it all. And it comes just about five minutes into the movie.

“I’m pulling for women,” Demme told the Los Angeles Times in 1991, prior to the film’s release. “I’ve got enough estrogen in me to identify with women. I don’t have any difficulty with that.”

Silence of the Lambs does not soft-pedal its horror, but Demme was shrewd enough to show that our joys are all the sweeter because of life's vicious design. Just look at the way Buffalo Bill (the serial killer driving the action)'s first victim dances in her car to Tom Petty. She may be victimized, but she's no victim; she's in the middle of orchestrating her own escape when Starling happens upon her in the climax.

After coming under fire for his depiction of the Buffalo Bill, a man who skins women in order to dress himself in their womanhood, Demme responded with Philadelphia, a film about a discrimination case, starring Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington at the peak of their powers. Philadelphia similarly caught flack for its depiction of the nobly suffering Hanks as a man dying of AIDS for our sins, but the film is, as usual, bigger than its central ideas. It should be remembered for its reveries, for the painterly depictions of Hanks' journey. For his face as he hears his bosses making homophobic slurs at a health club, his sinking into a blissful dream state as he hears a piece of music for the hundredth time, clinging to his IV like a cane and conducting with the other hand, red light blaring down on him from nowhere.

Like Steven Spielberg before him, Demme used his Hollywood platform to depict the mistreatment of black women in America. With Oprah and Danny Glover (reunited after The Color Purple) leading the cast, Demme crafted Beloved, an aching portrait of femininity under attack in an America that unfortunately feels closer than ever, thanks to our current political climate. Demme's deeply expressive images make us feel every hill and valley that these women suffer. Like most of his fiction, Beloved was hard-balled by critics, but it's well worth revisiting.

Stop Making Sense, Demme's first major doc, is quite simply the most joyful expression of music ever put on film.

Also worth revisiting is Demme's blistering remake of The Manchurian Candidate, which recasts the cold war thriller as Bush-era parable about the rich planting their children in undeserving power. It opens powerfully, with Jeffrey Wright and Denzel Washington meeting in close-up. Washington is composed at first, but then his eyes start to water slightly, fear and disorientation creeping in. Wright is a mess; sweaty, unshaven, bleary-eyed, and broken. We'll find out later that they've had their minds corrupted by the government and their identities stolen. They attempt to warn us of the horrors of what America can do to black people, years before Get Out and the Sunken Place.

Demme used the close-up like no other American filmmaker—as a site of confession, with characters looking directly at the audience, erasing our distance from them. Who can easily forget Silence of the Lambs' "quid pro pro" scene?

But Demme had already become a veritable documentary icon with the best rock doc known to modern history. 1984's Stop Making Sense, his first major doc, is quite simply the most joyful expression of music and the sense of community it inspires ever put on film. The Talking Heads rocket through their hits while Demme coolly watches the inner workings of the stage show, put on by frontman David Byrne. Demme's clear awe at the work that goes into putting on such a special performance is infectious.

Demme would later transport us to the farthest reaches of the world (and of one man's subconscious) in Swimming to Cambodia, an adaption of Spalding Gray's hit stage show about his life and career. Demme would also make several films about the great singer-songwriter Neil Young, clearly identifying with his pastoral rebelliousness and ability to paint pictures of the people suffering all over the world in order to celebrate them even as they're being forgotten.

There's much of this same empathy in Demme's studies of Jimmy Carter and New Orleans residents, including Carolyn Parker, about whom he made documentaries following Hurricane Katrina. Demme's final film, Justin Timberlake + The Tennessee Kids, returned him to the territory he covered in Stop Making Sense. It's an effulgent look at a stage show and its dozen or so players as they spread out all over a Vegas stage, bringing their music to every single member of the packed audience. It's joyful, boisterous, humane, and sincere. It's a collaboration. It's Demme all over. It's what he did best.