How Luis Buñuel Used Cinematic Interruptions to Capture Life's Absurdity on Film

If the director you’re about to learn about seems enigmatic or incongruous, life is that way too.

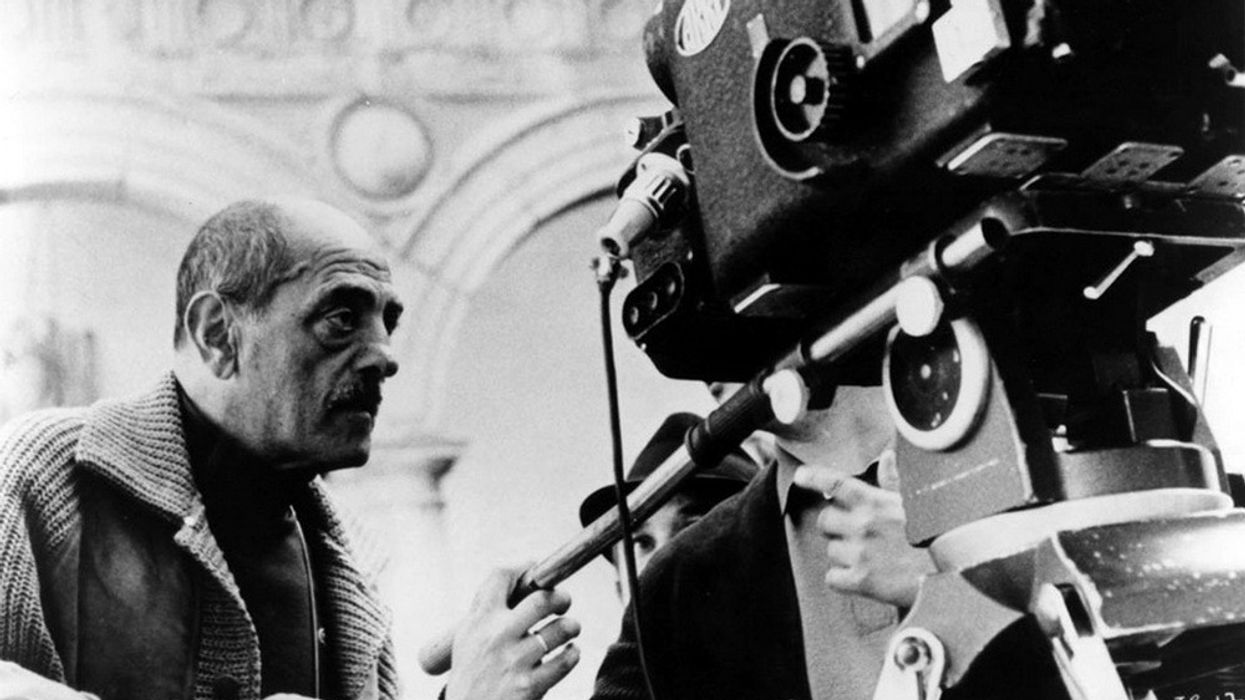

The late surrealist director Luis Buñuel loved to shake things up with his unique brand of cinema, especially in regards to class, religion, and conformity. To celebrate the day the great auteur came into this crazy, crazy world 116 years ago, we've decided to share a series of video essays from the Institute of Contemporary Arts (edited by Cristina Álvarez López) that explore his cinematic and narrative techniques. Check them out below:

These essays reveal several interesting concepts about Buñuel's approach to filmmaking, mostly surrounding the dance he does between realism and surrealism, and though we could spend the rest of eternity unpacking them, let's focus on one in particular that is especially intriguing: the director's use of "interruptions" as a cinematic tool.

"Luring us into the deceptive charms of narrative as well as those of his character, Buñuel undermines the stability of both attractions by turning interruption into the basis of his art." --Jonathan Rosenbaum (Sight and Sound)

Human beings have a natural emotional flow, so -- naturally -- narratives follow a natural flow. We see this in traditional story structure: beginning/middle/end where there is a rise in action that then leads to the denouement -- the climax. The tension of a scene rises, rises, then rises some more before it's released in a wave of complete closure-induced splendor.

However, if this progression is interrupted, it makes for a frustrated audience that is still seeking release from the emotional built up. That is where Buñuel's brilliant technique is realized, because he's essentially forcing the audience to become active participants in the film experience rather than passive viewers.

Consider Jonathan Rosenbaum's analysis of the "Buñuel Touch" from this 1973 Sight and Sound article:

One never finds in his work that grace and economy of narration, that sheer pleasure in exposition -- On the contrary, Buñuel’s usual impulse is to interrupt a narrative line whenever he can find an adequate excuse for doing so -- a joke, ironic detail, or startling juxtaposition that deflects the plot’s energies in another direction.

Even if you've never seen a Buñuel film, you might've seen this technique before. Lars von Trier uses interruptions to stymie the natural emotional progression in the second installation of his "Depression Trilogy," Melancholia. Though more subtle than Buñuel's approach -- a phone ringing or a severe weather -- von Trier uses interruption in the form of Justine (Kirsten Dunst) repeatedly leaving her wedding reception, which creates an agonizing feeling of emotional dissatisfaction in the progress of the story. (The one and only time I've ever spoken in a theater was to tell this character to just stay in the damn room.)

The technique reflects Justine's restlessness and anxiety back onto the audience, and Buñuel uses it in the same way -- but with a mustachioed-Dalí twist. Rosenbaum's article notes film critic Andrew Sarris' observation that Buñuel's "camera has always viewed his characters from a middle distance, too close for cosmic groupings and too far away for self-identification," to which he replied:

The singular achievement of Buñuel’s crystallized style is to allow both these viewpoints to function -- to let us keep our distance from the characters while repeatedly recognizing our own behavior in them.

In other words, Buñuel keeps his characters at a certain observational distance -- one that does not grant the audience the satisfaction of being immersed in an illusory environment, but instead puts them face to face with reality.

"Um, are we still talking about one of the most lauded surrealist filmmakers here?"

Yes! Buñuel was well aware of the world's eccentricities -- the fact that it's an incongruous enigma. His approach to depicting the absurdity of real life was to make films with absurd images -- to fight fire with even more fire.

Happy Birthday, Luis Buñuel!

Source: ICA