The Story of Story III: Which System Helps You Write the Best Screenplays?

What can history's most powerful writing systems, from Aristotle to McKee, teach us about successful screenwriting?

It can seem as though there are more screenwriting books than there are screenwriters, with every one promising to deliver “the secret” of a great script. Which begs the question: is there a secret? Let's take a look at a few writing systems, and see what we can find.

1. Aristotle's Poetics

Any survey of dramatic systems must, of necessity, begin with Aristotle, whose Poetics from 350 B.C.E. is the earliest example of what we now think of as the so-called "how-to-guide," though it was not written as such in the modern sense. Through Ancient Greek tragedy, playwrights and actors aroused a universal quality of "pity and fear" in the audience. If all went well, this feeling produced "catharsis" and so acted as a purgative which was beneficial to society (while contemporary drama is still capable of fulfilling this function, it's primarily in a secular context.) Poetics comprises, along with the surviving texts of some plays, the foundation on which Western drama is built.

For Aristotle, tragedy consisted of:

- The Plot (the arrangement of the incidents)

- Characters (who existed to act out the plot, and were far less important)

- Dialogue ("everything the characters say when they present an argument, or make evident in opinion")

- Spectacle (effects, special or otherwise; the most immediate, but least important as tragedy wasn't FX-heavy)

Two other aspects of Ancient Greek theater ("diction" and "song") are, for our purposes here, less relevant, as they focused on the rhythms of language and meter in Ancient Greek. As far as individual works, Aristotle considered the height of tragedy to be Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, first performed circa 429 B.C.E. It was the apotheosis of all Aristotle believed noble in drama. He believed a play was best when its actions caused each other, a concept later codified by the Romans as post hoc ergo propter hoc (or, after this, therefore because of this). This illusion of causality is actually one of the most common logical fallacies in real life. There are theories that humans evolved the ability to relate one event to the other, no matter how tenuous the connection, as a survival mechanism.

As a dramatic device, Aristotle favored it far more than a coincidental plot, or one based on a deus ex machina. He also believed in importance of the reversal (peripeteia), ideally when followed by an anagnorisis, or sudden recognition of the truth; both of these would lead to the denouement (a French word, with Latin roots, and a probable Greek origin, which means "unknot".) Almost 2,000 years later, in 1863, Gustav Freytag, a German novelist, would turn Aristotle's ideal structure into his famous triangle, now familiar to writing students the world over.

Having briefly covered the foundational system, we can move on to the 20th century, the movies, and the birth of modern dramatic structure.

For Egri, the essence of drama lies in its premise, which for him is the "microscopic" essence of the story.

2. Lajos Egri and The Premise

Lajos Egri's Art Of Dramatic Writing: Its Basis in the Creative Interpretation of Human Motives, first published in 1942, was a ground-breaking work, one of the first to delve into the importance of the psychological motivations of the characters. Previous how-to guides such as Plotto: The Master Book of All Plots, written by an absurdly prilofic dime-store novelist, consisted of every possible permutation of dramatic situation the author could think of (for the record, he could think of 1,462 situations.) Egri's book was a more high-minded affair, an influential text in the study of theater and a sort of analog to the new style of Method Acting.

For Egri, the essence of drama lies in its premise, which for him is the "microscopic" essence of the story. The premise is a distillation of the idea of the play, e.g. greed leads to destruction or excessive pride leads to a downfall. He stressed that characters were the conduit to the expression of the plot, contra Aristotle, who held that characters were merely conduits for the actions of the story.

Egri, too, had his own ideas about causal relationships in a story, ordered from best to worst: while foreshadowing of further conflict and a slowly escalating conflict were good, static and jumping conflict were bad. Artistotle, too, rated random conflict as the worst.

Both of them believed in a concept of universality of dramatic character, too; Egri's, though, was borne of the modern, psychological viewpoint of his time. A character, he wrote, should be someone with whom the audience can identify, someone the audience can project themselves onto; he was of the opinion that a writer should question their character (metaphorically), interrogating them to discover their wants, needs, histories, physical and mental traits, etc. But enough of this theatre stuff. Let's get to the movies!

Snyder's secret rested in the marriage of two elements: the "logline" and the "beat sheet."

3. Saving Cats!

Prior to the publication of Syd Field's Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, screenwriting had been a relatively insular art form. The complicated rules of formatting had been mostly passed down through the studio system or outlined in books like The Complete Guide to Standard Script Formats, which were usually film school textbooks. It was Field who made screenwriting accessible to the general public. Field's book unleashed a torrent of guides, and among the most successful has been Blake Snyder's Save the Cat series.

Snyder's secret rested in the marriage of two elements: the "logline" and the "beat sheet." Snyder's logline is a bit like Egri's premise, only it contains a few extra elements. For Snyder, the ideal logline consists of the following elements: "On the verge of a Stasis=Death moment, a flawed protagonist has a Catalyst and Breaks Into Two with the B Story; but when the Midpoint happens, he/she must learn the Theme Stated, before the All Is Lost, to defeat (or stop) the flawed antagonist (from getting away with his/her plan)."

An example of this, from his site:

"On the verge of another “suit and tie” assignment, a tomboy FBI agent is assigned to go undercover in the American Miss Pageant and has a complete makeover to blend in with the other contestants; but when the pageant receives a new threat, she must learn she can be a woman and tough, before she gets thrown off the case, to defeat the warped pageant organizer bent on revenge. (Miss Congeniality)"

Snyder's "Beat Sheet" consists of 15 steps each film should (ideally) follow, for maximum connection with the audience. The title of the series comes from so-called "save the cat" moment located on each beat sheet in each screenplay that follows his system; somewhere within the opening minutes of the film, we must see the protagonist "save a cat," i.e., engage in some action that makes the audience root for the character. In addition, Snyder's system has 10 genres and 50 sub-genres. Sadly, Synder passed in 2009, but his system remains incredibly popular. And, unlike many gurus, Synder was a working screenwriter, with a track record of selling high-concept commercial scripts, including Stop! Or My Mom Will Shoot, and Blank Check.

4. Story, or, the revenge of Robert McKee

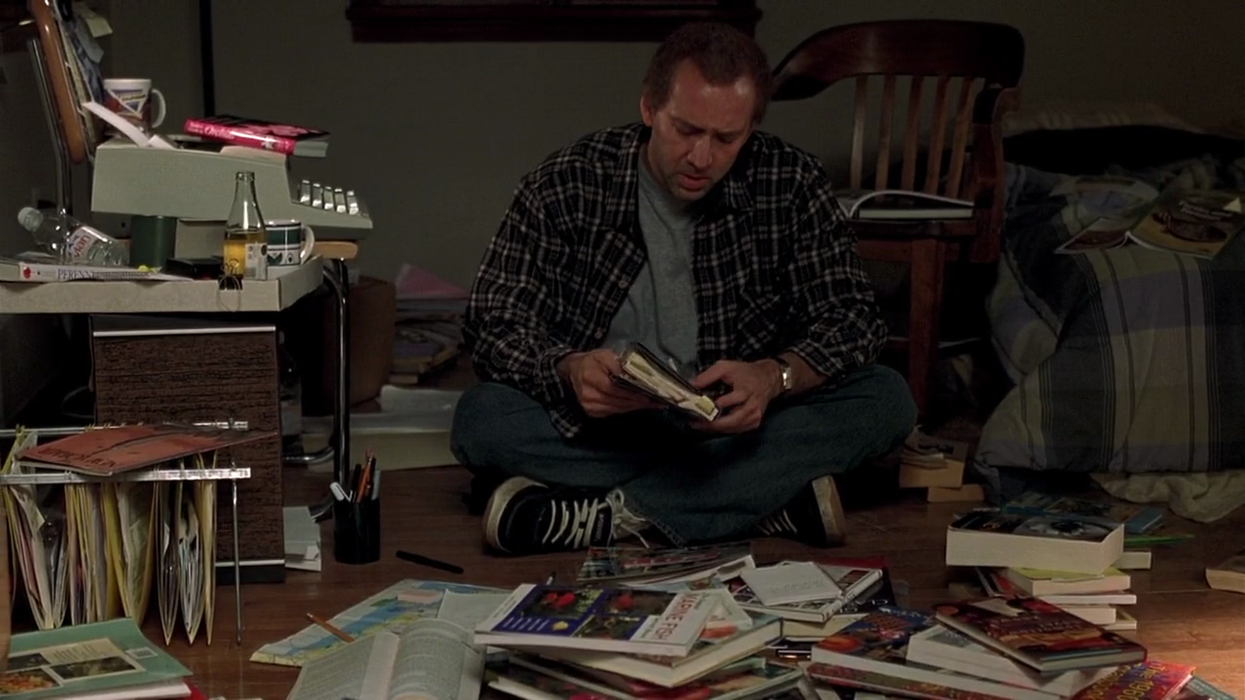

Today, probably the most famous script writing system in Hollywood is one based on the ideas of Robert McKee, who conducts seminars all around the world. He was immortalized on film by the actor Brian Cox, who portrayed the thundering guru in the Spike Jonze film Adaptation, memorably dressing down Nicolas Cage's sad-sack of a screenwriter.

A reporter fromThe New Yorker followed McKee around during one of his seminars, and had the man himself break down exactly what it is he does: "I’m repeating what I was taught, and then adding some little insights I’d had—but basically recycling Kenneth Rowe and John Howard Lawson and Aristotle, and putting it in a contemporary context...It’s obviously needed. I can see the emptiness out there.”

McKee's system is far too complicated to get into detail on here (and much of it is proprietary), but, in short, it consists of a "Controlling Idea" (similar to Egri's "Premise"). According to Dan O'Bannon's Guide to Screenplay Structure (another book on...well, you have probably guessed by now), by the screenwriter behind Alienand Total Recall, McKee's most elementary particle is the "Beat," defined as "a moment of action or behavior between characters." These combine to make "Scene(s)," or, "extended conflict-driven actions," and these scenes add together to change the character's values for good or ill, via a process of positive and negative changes.

One thing all of these systems share with each other is a reliance on the elements of drama, namely character and conflict, as laid down by Aristotle 2,500 years ago.

In O'Bannon's summary, a McKee script contains about 40-60 scenes, structured in segments of as many acts as the story demands (but no less than three). McKee also relies on the concept of the "Gap," or difference between a character's expectations for their actions and the results of those actions. Unlike Snyder, McKee has only determined 25 genres, though he does have five requirements for a successful story:

- An Inciting Incident, which occurs within the first quarter of the script

- Progressive complications, built up through beats and scenes, and changing the tone of the story from positive to negative and back again

- A crisis moment, when the character reaches their crucial choice (this functions as McKee's "obligatory scene", or, as O'Bannon puts it, "the emotional high-point")

- A climax (precipitated by the crisis, the result of the decisions made at that moment)

- And, finally, a resolution, which is either positively or negatively charged, or ironic, in a realistic fashion

For sheer detail, there's no one (but no one) who can beat McKee, but unfortunately you'll have to attend a seminar in or buy his book to get the proprietary details.

After this (brief) survey of screenplay systems (I didn't even go near Dramatica), what have we learned? Well, for one, there are a lot of screenplay systems. And with the odds of selling a spec screenplay pretty long, it doesn't look as though there will be any shortage of screenplay guides (or gurus) in the near future, especially with global box office at an all-time high.

"Hollywood is a town run not by artists, but by number-crunchers, and artistic principles will be easier for them to digest in a form which they're already familiar: flowcharts, piecharts, graphs, and the like."

It seems pretty self-evident, though, that one thing all of these systems share with each other is a reliance on the elements of drama, namely character and conflict, as laid down by Aristotle 2,500 years ago. In his book, O'Bannon muses the popularity of these systems might be based on the fact that, "Hollywood is a town run not by artists, but by number-crunchers, and artistic principles will be easier for them to digest in a form which they're already familiar: flowcharts, piecharts, graphs, and the like."

Each of these systems, with their sheets, principles, geometric shapes, etc., are not only comforting to executives, but also to writers. The universal rules of story, developed over millennia, contain elements common to humanity, dating to a time before there were dates, originating in a place before there were maps. Today, in a world of global cinema, it's up to you, as a writer, to pick whichever system works for you (or invent your own! or don't use one at all!) and come up with the next idea that will move us to joy, laughter, tears, anger. Story is, after all, perhaps the most fundamental, universal human experience, and everybody has their own to tell. So get cracking! Or, you know, you could write a how-to guide on how to write how-to-guides. Which gives me an idea. BRB.

FINAL FADE.

Check out the first parts of this series: The Story of Story: How I Learned to Stop Worrying & Love Structure and The Story of Story, Part II: This is Your Brain on Story