14 Beautifully Shot Horror Films That Changed Cinematography Forever

Talk about killer cinematography.

Cinematography is one of the most important elements of a horror film. With their game-changing technical innovations, surreal imagery, and the power of subjectivity, these 14 masterpieces changed the course of cinematography—and the horror genre—forevermore.

1. The Phantom Carriage (dir. Victor Sjöström, 1921)

This Swedish film has widely influenced directors throughout cinema history—most notably, Ingmar Bergman, whose film The Seventh Seal paysdirect homage to The Phantom Carriage, and Stanley Kubrick'sThe Shining, which features multiple thematic and visual similarities, such as the famous ax scene. To tell the story of a ghostly coachman who comes to steal the souls of the dead after the clock strikes midnight, director Victor Sjöström and DP Julius Jaenzon employed double exposures, at the time a highly innovative special effect. The superimpositions were layered up to four times, providing the illusion of ghosts wandering in and out of the film's elaborate sets. Each "ghost" was lit differently with a filter. Jaenzon followed them with a hand-held camera that was capable of exceptionally deep focus—highly unusual for the time—made possible with studio lighting.

The film also features complex narrative structural elements, such as meta-flashbacks (or flashbacks-within-flashbacks) that diverge from stories as they are being told, fusing past and present into one ethereal reality.

2. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (dir. Robert Wiene, 1920)

Considered the quintessential work of German Expressionism, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is the story of a deranged hypnotist who uses a sleepwalker to commit murders. Cinematographer Willy Hameister used no-frills camera work to emphasize the film's elaborate hand-painted sets, featuring twisted cityscapes, spiraling streets, and nightmarish forms. The sets were designed with distorted perspectives—they feature not a single right angle—in order to create a disorienting and unhinged world. Shot entirely in a limited studio space, each set was restricted to 20 feet in width and depth.

In addition to its fantastical use of set design, Robert Wiene's film bears significant historical importance; Dr. Caligari can be seen to represent the brutal German war regime, while the sleepwalker stands in for the common man who shows deference to a murderous authority.

Not only is Nosferatu a seminal horror film, but it is also one of the most influential films of the silent era—and one of the first major public cases of intellectual property law. Because it was based on Bram Stoker's original Dracula novel (though with character names, setting, and plot details changed), the Stoker estate sued for copyright infringement. The court ruled that Nosferatu was indeed a derivative work and ordered all copies of the film to be destroyed, but one print had already been distributed worldwide; Nosferatu was subsequently revived by a cult following.

Unlike the Expressionist techniques achieved in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari with studio lighting and elaborate sets, Nosferatu was shot almost entirely on location; the natural environment of the castle, landscapes, and town were contrasted with unnatural lighting. Cinematographer Fritz Arno Wagner introduced camera tricks to the mise en scène—several shots were printed in reverse-negative, while other scenes were under-cranked, and still others utilized stop-motion photography, such as in the film's most famous shot, in which Count Orlock pops out of a coffin.

"To watch F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu," wrote Roger Ebert in 1997, "is to see the vampire movie before it had really seen itself... the film is in awe of its material. It seems to really believe in vampires."

4. Vampyr (dir. Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1932)

Adorned with mist and rolling fog, Carl Theodor Dreyer's hypnotic Vampyr elicits an overwhelming sense of dread. The washed-out, soft focus of Rudolph Maté's cinematography enhances the striking visuals, all of which were filmed at dawn. But the greatest aesthetic achievement in this film happened by accident. At the beginning of production, when Dreyer first screened a scene's rushes, he noticed a gray sheen to one of the takes. Upon further investigation, he and Maté discovered that a false light had been projected onto the lens. They loved the look so much that they deliberately recreated this light by directing a spotlight hung with a blacklight onto the lens.

5. Psycho (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1960)

Hitchcock's famous shower scene was so complicated to shoot that it required 78 camera setups and seven days to execute. The bathroom set was built with collapsible walls in order to maximize the usable camera angles; in the final cut, 90 splices of split-second shots from different angles create an unnerving effect in this scene. Cinematographer John L. Russell used a fast-motion reverse shot to give the impression of the knife entering Lila's abdomen. He also made use of a wide variety of subjective close-ups throughout the film, such as Lila's hand pushing open a door, which served to enhance a sense of immediate danger for the audience.

6. Kwaidan (dir. Masaki Kobayashi, 1964)

Kwaidan, which translates to "ghost stories," is a compendium of four classic Japanese ghost tales that plays less like a horror film than an eerie fever dream. Director Masaki Kobayashi and cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima gave each story its own hand-painted set, which was intricately designed to reflect the changing mood and narrative arc of each shot. Built in an airplane hangar (the only space big enough to accommodate them), the set pieces themselves are works of Expressionist art. Kobayashi's meticulousness is evident in every frame. In conjunction with Miyajima's creative lighting techniques (such as backlights of every color), watching Kwaidan is like being transported into an uncanny alternate reality.

Roman Polanski's horror masterwork was shot with a budget of $300,000. Excited by the prospect of improving upon the aesthetics of Knife in the Water, which he thought looked "absolutely dreadful... very wishy-washy, with no real blacks at all," cinematographer Gilbert Taylor turned down a Bond movie to make Polanski's sophomore feature.

Repulsion is indeed characterized by extremely contrasty black-and-white. It increasingly adopts the perspective of its disturbed protagonist; as she descends into a massive psychotic break, Taylor unmoors the camera. He shot much of the film with a handheld Arriflex with a very wide lens and "a tiny tobacco tin on the front, fitted with a wee bulb to add a bit of fill—just enough to see Catherine Deneuve’s skin in the shadows until I moved in close." Polanski remembers that Taylor used mostly reflected light bounced off the ceiling or walls, never consulting a light meter.

8. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (dir. Tobe Hooper, 1974)

Another notable low-budget sensation, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was filmed with $300,000 and mostly unknown actors cast in central Texas, where it was shot. Cinematographer Daniel Pearl shot on 16mm with an Eclair NPR 16mm camera, using fine-grain, low-speed film that required four times more light than modern digital cameras. The film's final shot, in which Leatherface swings his chainsaw with primal fury in the early morning light, has become one of the most iconic in cinema history.

9. The Shining (dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1980)

John Alcott 's cinematography emphasizes isolation and paranoia with unsettlingly cold, symmetrical imagery. It's stunning throughout, but it will go down in the history of cinematography for its innovative use of Garrett Brown’s Steadicam, which Kubrick hired Brown himself to operate in what Brown would later term "the Steadicam Olympics." Riding on a wheelchair to capture Danny's low-angle point of view as he rode on a tricycle through the halls of the Overlook Hotel, Brown honed his operating skills by repetition; on the first day of the shoot, Kubrick had him do 30 takes of a traveling shot in the lobby. The technique was most famously used for the hedge maze chase, for which he built a variety of special mounts:

We determined by testing that the 9.8mm Kinoptik looked best, and that the ideal lens height was about 24 inches. This combination permitted a tremendous sense of speed and gave the correct appearance of height to the walls. The distortion was negligible when the camera was held level fore-and-aft. Much of the shooting consisted of fluid moves ahead of or behind Wendy and Danny as they learn their way through the Maze. Some of the best moments came as we followed them right into a dead end and back out again in one whirling move. I also made some tripod-type shots in the center of the maze since it would have been time-consuming to lug in the equipment to make a conventional shot.

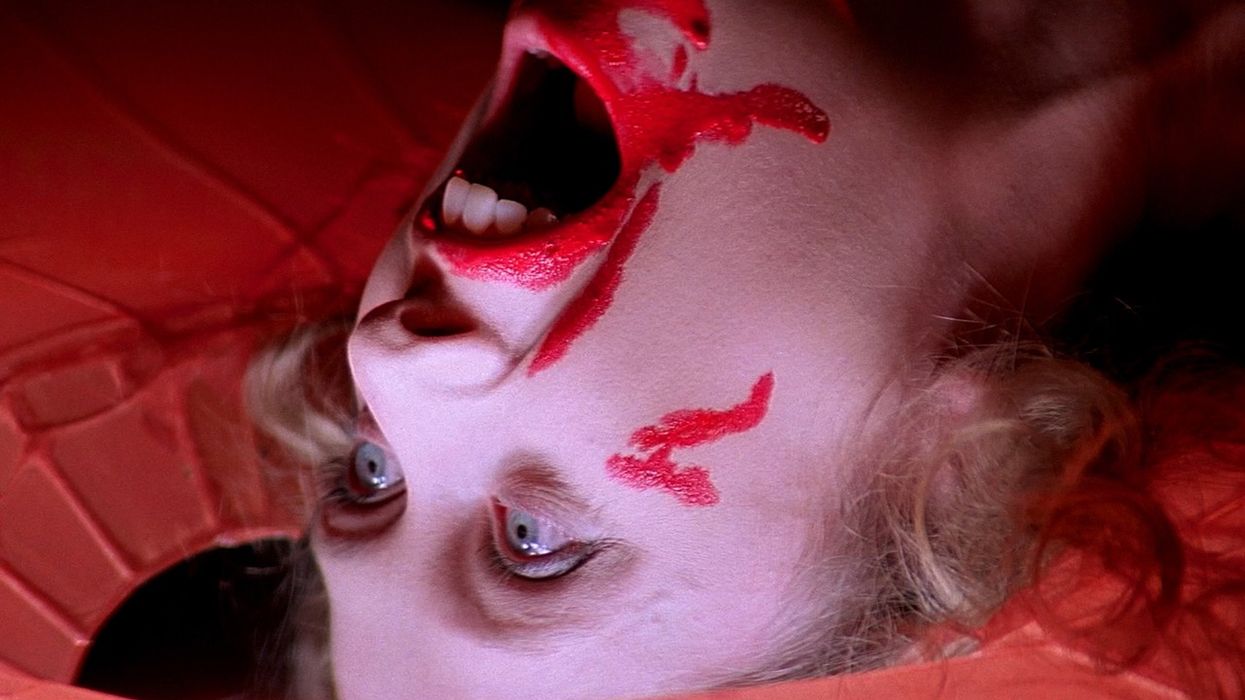

Most known for its use of saturated color to a psychedelic effect, Dario Argento's surreal Giallo film plays like a violent neon nightmare. "A [horror] film brings to the surface some of the ancestral fears we hide deep inside us," said cinematographer Luciano Tovoli, "and Suspiria would not have had the same cathartic function if I had used the fullness and consolatory sweetness of the full-color spectrum." (He "contaminated" each primary color with yellow.)

Argento asked Tovoli to film with an outmoded IB stock from Kodak with a high layer of gel at 30/40 ASA. To light the actors, Tovoli used a large arc light and placed frames made of tissue and velour paper very close to the actors’ faces. To light the elaborate sets and locations, he bounced light onto a mirror in order to sharpen the images more so than if they were directly illuminated.

Once the film was shot, Argento gave the negative print to Technicolor, who then split the color negative into three separate black and whites: one for red, one for blue, and one for green. Printing one color on top of the other gave the film a shimmering look with vivid color definition that far exceeded the emulsion-based print.

11. Halloween (dir. John Carpenter, 1978)

To create what may be one of the scariest opening scenes of all time, John Carpenter and cinematographer Dean Cundey took a chance on what was, in 1979, the newest technology: the Steadicam. Then called the Panaglide, the device allowed the camera to be fitted to a camera operator for far-ranging and unbroken shots. "It was a new technology that we learned to use by the seat of our pants," Cudney remembered. The opening scene, which was written over three pages as one fluid shot, had to be captured on one shooting day due to budgetary restraints.

"We couldn’t have done it without the Steadicam," Cundey continued. "There was no other piece of equipment that would have been able to go across the street, look into the house, go into the kitchen, up the steps, into a bedroom, and back down again." (Here's test footage the team did with the Panaglide before shooting.)

The distinctive POV shot from inside the killer's Halloween mask was an optical added in post-production. The obstructed vantage creates unbearable suspense in the scene.

12. Blair Witch Project (dirs. Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, 1999)

Though Cannibal Holocaust was technically the first film to use the found footage technique, The Blair Witch project built upon its foundation to a horrifying degree. The co-director and cinematographer Neal Fredericks, who was tragically killed in a plane crash at age 35, chose to employ found footage because it served the film's pseudo-documentary narrative, allowing for a radical first-person perspective. The cinematography is shaky and entirely handheld; oftentimes, the actors look directly into the camera. Though filming only lasted eight days, the film took more than eight months to edit. Shot for next to nothing, it eventually grossed more than $250 million, rendering it one of the biggest independent box office successes of all time.

"Blair Witch didn't need to be lit, so he didn't light it," Sanchez told AP shortly after Fredericks' death. "It didn't need a camera operator, so he didn't operate. What he did do was make sure those actors knew everything they could and had everything they needed to keep shooting, to keep getting those images into the camera."

13. Silent House (dirs. Laura Lau, Chris Kentis, 2011)

Shot in what appears to be one single take, Silent House was actually the product of 12-minute sequences stitched together in post-production. The shots were limited to 12 minutes because the team chose the Canon EOS 5D Mark II for the job, which has a 12-minute file record limit. But the single-take gimmick, inspired by Hitchcock's 1948 Rope, is effectively seamless. The co-directors and cinematographer Igor Martinović perfected the illusion by rehearsing for two weeks in the abandoned house, which they lit with only flashlights, lanterns, and candles.

"The concept here was to get the camera into as subjective an angle as possible, to really get into the perspective of the main character," said Martinović. "At the time we shot the film, the 5D Mark II was the only camera that could give us what we needed. It was very small, high quality, affordable, and we could get it into tight spaces, move easily with it, transfer it from one operator to another when needed—it provided us with the flexibility we required. Today, it’s already a different game."

The camera crew also had a handheld rig from Redrock Micro and a prototype on-board monitor from SmallHD, which allowed Martinović to monitor 720p from the 5D Mk II (a feed-through of the HD signal went into a wireless transmitter in a backpack to feed the video village).

14. Under the Skin (dir. Jonathan Glazer, 2013)

Much of Under the Skin was shot with a hidden camera called a OneCam, which Jonathan Glazer had custom-built for the movie. "We needed a camera that was small enough to hide," said Glazer, "but had the quality that we needed to project and do the visual-effects work. It didn’t exist, so we built it." Actually, Glazer and cinematographer Daniel Landin had 10 cameras built; sometimes, they used two, while other times they used all 10.

The OneCam is a matchbox-sized CCD that's able to fit 16mm lenses. "We shot much of the film like that, where we could build the cameras into the dashboard in her car, or hide them in street furniture to watch her walking down the street and not alert the general public that there was any filming going on at all," Glazer continued. "Much of the film was shot covertly like that."

Glazer ended up with 16 hours of footage from the OneCam per day, or 6TB worth of data. In a single day, "the crew shot as much data as a film would over the entire course of a feature production shoot."

The rest of the film's surreal imagery was shot with the ARRI Alexa.