Oscar-Nominated 'I Am Not Your Negro': How Editor Alexandra Strauss Cut an 'Impossible' Film

Editing is key to the power of Raoul Peck’s Oscar-nominated documentary.

How do you revive a larger-than-life character who has been dead for 20 years? How do you tell a quintessentially American story when you are not from the United States? How do you wrap some of the most pressing modern social issues into the story of one man and his intimate friendships? And how do you make a film that is composed largely of historic photos and footage feel urgent and contemporary?

These were all objectives of Raoul Peck’s powerful, Oscar-nominated documentary I Am Not Your Negro, and perhaps what led Peck to call the film “impossible to make.” But he was ultimately able to answer these questions thanks to the work of French editor Alexandra Strauss, who wove a trove of archival materials and film clips together with a visceral soundtrack and a moving voiceover by Samuel L. Jackson into one of the year’s most vital documentaries.

One of the year’s most vital documentaries.

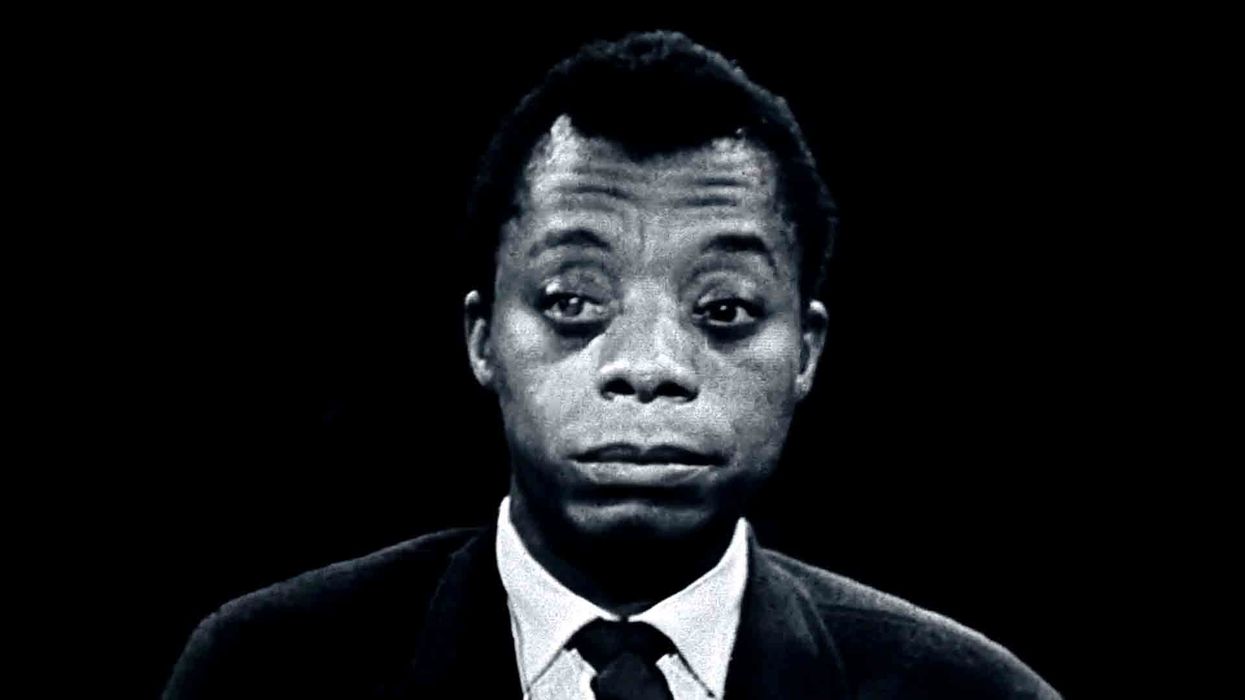

I Am Not Your Negro imagines how writer and social critic James Baldwin’s magnum opus would have been realized if he had not died only 30 pages into writing it. The book was to be about the lives and murders of three of Baldwin's close friends: the Civil Rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. Although four of the men left this world decades ago, the film reminds that we are still grappling with their legacies today.

No Film School spoke with Strauss before the film’s US theatrical release to learn about how she approached this complicated narrative.

No Film School: Raoul Peck said that this film was “impossible to make.” Why do you think that is, and how were you able to help make it possible?

Alexandra Strauss: The main work was to give life to James Baldwin and to create cinematography with only words. When you work on a film, you always have a story, even if you make a documentary, but this was completely different because it was not a classical story.

It was really a big deal to make a film like I did: to find images, and most of all, to get the words [of the narration] listened to by people, which is quite difficult when it's not telling a fiction story, but is telling ideas. That’s maybe why he said it was difficult and impossible.

NFS: How do you think that you helped him rise to the challenge?

Strauss: At first, I had the text. There was all this video with Baldwin, and the first thing that we wanted to know was if it could work going from a voiceover to Baldwin speaking. We wanted audiences to just align and be taken in by the speech and by the thought. I first worked with a voice; then, I tried to put images under it. It was like everything was possible. It was like jumping into a wide sea of images.

"It was like jumping into a wide sea of images."

I worked a lot alone. I work a lot, and then we look at what I do and we discuss, and then he goes away, and I work [again]. I have quite a lot of space to try a lot of things, which is really nice.

Strauss: It depends on the director, of course, because often young directors want to see it. They want to be there all the time. When they get more comfortable with themselves, they prefer to look at the work when it's done and to discuss it and then you go back alone to work.

With Raoul, it's the third time we’ve worked together. He trusts me a lot and also, he asks a lot. He wanted the movie to be violent and really strong, and he didn’t want any images in it to be meaningless. He wants everything you put in to have a meaning.

"Young directors want to see [the footage]. They want to be there all the time."

Finding images, I had a really good archivist working in the room close to me, so I could ask for things. [During] the first months, we didn't know what would be possible using archives, so we used everything we liked. After, of course, we had to deal with rights and reality, so we had to exchange some photographs and make a few extracts because we couldn't use them or the music.

But it was really a lot of freedom in the beginning. Raoul picked out a lot of pictures. It was like we had a lot of colors, and we had to paint with them, to make it possible to listen to the words, which were strong.

NFS: What else did you have to work with, besides the images?

Strauss: I also had to make a lot of choices in the text because it was too long. In film, you need to be really acute. You need space. You need a lot of moments [during which] the audience can think or dream, or to feel emotions, so you can't have a voice all the time. It’s too much. That was a lot of work—to find where to stop and where to dream. We tried to use a lot of music for pacing, but also, to show all these images that were shot from today in America: the roads, the sea. We tried to find space in between the words.

NFS: The film is about a writer. You are also a writer in addition to being an editor. What similarities do you find between writing and film editing?

Strauss: Of course, it's about storytelling. In editing, you work for someone else’s world, which is, of course, completely different from trying to write your own words or trying to find a truth about something hidden.

When you work in editing, you’re completely in the world of the director. You can change worlds depending with whom you work. For me, editing films is much more like sculpting materials. It's much more physical. I try to work with intuitions and feelings, and to let go and to trust what I feel about how long a shot should be.

“For me, editing films is like sculpting materials. It's much more physical [than writing].”

NFS: Speaking of getting into the world of the director, you're a white French woman, and this film is about an African-American man. It deals with very American topics. How did you get into the mindset of your subject?

Strauss: I've worked with Raoul a few times already, and I got really acquainted with Baldwin [reading and] looking at him a lot. Even now, when I would look at pictures of him smiling, I feel very close to him. It's something I like to do—to try to immerse [myself] in someone’s thoughts.

When I think about French history and politics in France today regarding foreigners, and how French people act now with all the immigration, a lot of things that [Baldwin wrote about] also spoke to me, so I could connect. Also, I’ve loved American cinema since my childhood. But maybe the distance helps. I mean, you're not completely in, so you have an objective view.

NFS: In your essay about the work, you talked about the challenge of trying to not just make a biographical film or a civil rights film, but make something bigger. How would you advise someone who wants to make a film that's broader than one specific issue?

Strauss: It's a really a question of choices. Editing is always a question of choices. I think that when you look at a film, you should never feel the editing.

Strauss: In the text that Raoul had picked out, there were a lot of things about Baldwin speaking about his childhood and many biographic things about his father. We had to make choices to cut those and to be really simple in what was saying. If it's too complicated, people can't follow.

Again, it's a question of choice. For example, I edited many more sequences about civil rights, which we cut completely. There had been a lot of films about that and it was not the point of this one. When you want to say too much, people can't hear.

NFS: On the technical side, what tools do you use in post?

Strauss: I only work on Avid. The first two months, the archivist gave me really terrible pictures from the internet with the time codes on it, sometimes with the name of the library on it. It was just terrible to look at and to work with it.

When it came to working on the photographs, I worked with a graphic designer. I made some pre-zooms or movements in the pictures, but I don't like to do that, so I made sketches and I sent them to the graphic designer who then worked and sent me back some propositions.

NFS: There was an incredible soundscape in this film, between the voiceovers, the archival interviews with Baldwin, and the music. How does music play into your editing? Is it there the whole time?

Strauss: I work with the music a lot, from the beginning. Of course, there was a sound editor at the very end of the process. I always try to be very precise when I work with music and voiceover. I think it's like I was saying: sculpting. It's like a material, so you have to make something with it.

"When you say too much, people can't hear."

NFS: So music is like one of your materials?

Strauss: Yes, yes. Even if you don't keep it. I knew I was going to work with the composer because we did in the previous films, so I used old music from him and I tried it in places. I think it's very important to work with music from the beginning, to find the pace, to find the rhythm, to know where you put music or not.

Strauss: I don't know if the composer likes it, but we have always worked like this. I put in music that he composed for other films, and afterward, he works on it and proposes new things. So we don't have to get used to it.

It's like a voice. I worked with another voice and we liked it a lot, but it was not really playing. We got used to it but when we recorded with Samuel L. Jackson, it gave a new energy and we had to change little things. He was so professional and so deep in it.

"At the beginning, we didn't know where we were going, but we knew what we didn't want."

NFS: Do you have any other advice about using archival materials to craft a story?

Strauss: We were lucky that we could use a lot of what we were working with, but they’re just materials. The only advice is to feel free to use it and not to be hindered by permission at first. With Fatal Assistance, another documentary I edited for Raoul, I had something like 200 hours of footage. Of course, you can't use everything, but you have to look what is fitting.

NFS: So is it more important that you have a clear vision at the beginning?

Strauss: At the beginning, we didn't know where we were going, but we knew what we didn't want. If you go through the Baldwin text, you already have the meaning, so you have to find images that either fit or that are completely the opposite to [create] some kind of humor, or sometimes to [create] some kind of violence.

For example, when Baldwin speaks about the American image and films and culture, it's often about the gap between what you see on film and the intentions and reality behind it. We used Doris Day and very violent street scenes. You have to know what kind of effects you want to have.

My last piece of advice is that you have to be able to keep morale. Know your limits. You can't do everything.

‘I Am Not Your Negro’ opens in US Theaters on February 3, 2017. You can read more about Strauss' approach to the project on her blog.