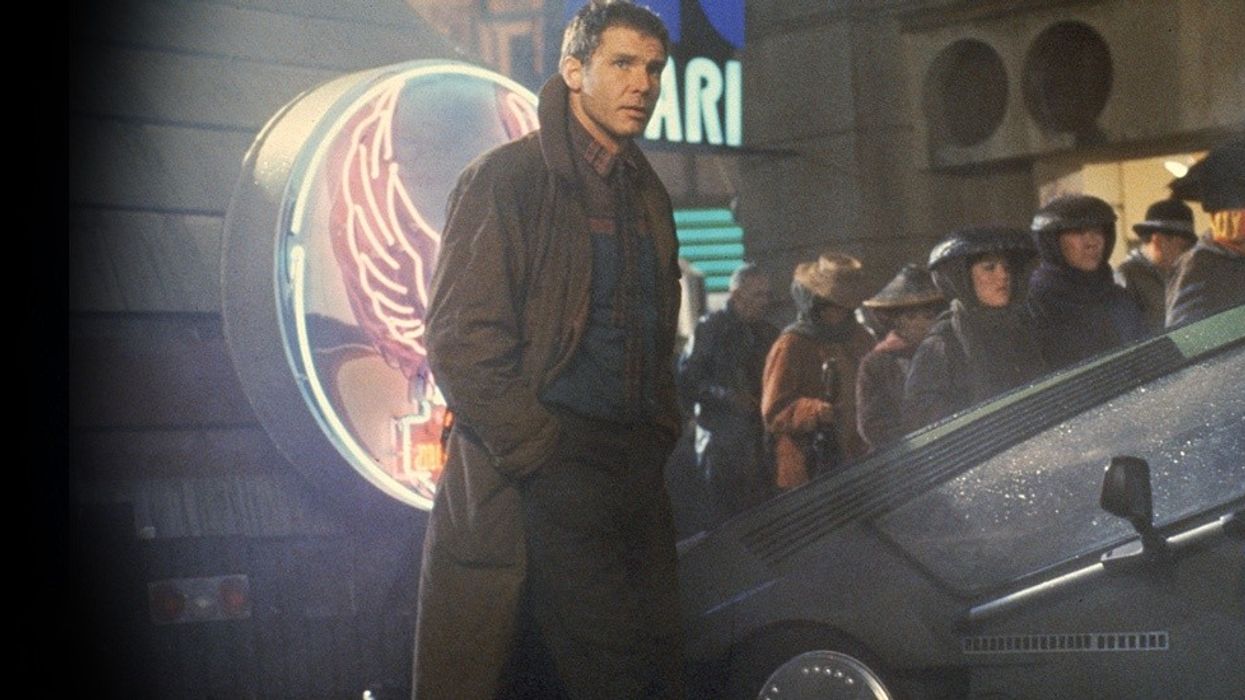

Watch: Discover How 'Blade Runner' Created a New Genre

Take a deep dive into this indelible world of future noir that has influenced art and culture ever since.

To say that Blade Runner 2049 is eagerly anticipated would be to understate the case by orders of magnitude. The original Blade Runner, directed in 1982 by Ridley Scott and based on the Philip K. Dick novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? single-handedly created a new aesthetic. It was science fiction set in a world uncomfortably close to our own, yet canted just enough to hide in shadow. And, as Michael Tucker notes in this new video from Lessons from the Screenplay, "Blade Runner was the first film to truly take the thematic elements of classic film noir and integrate them into the science fiction genre." Here are three ways the film the did that, and in doing so, made film history.

1. The moral ambiguity of crime

According to Tucker, in one of the first books written on the subject of film noir, in the 1950s, the authors noted that: “It is the presence of crime which gives film noir its most constant characteristic.” But crime has always been a part of Hollywood film, so what's the difference here? According to the writers, it's that, “Now the moviegoer is being presented a less severe version of the underworld, with likable killers and corrupt cops. Good and evil go hand in hand to the point of being indistinguishable.”

In film noir, the powers that be are not to be trusted, and killers aren't always the bad guys, and it's at this new crossroads where we can locate the “mortal struggle inherent in all film noir.”

2. Death, or the nature of life itself

FIlm noir is, to be sure, a pessimistic genre, full of double crosses, false hope, and sordid imitations of a moral world. Furthermore, "The classic film noirs often tell stories about people who are trapped, creating a mood of inevitable doom," and doom is the mood that is predominant throughout Blade Runner. The earth is a shell of its former self, with almost everyone who could leave, already gone; those who remain, like Deckard, don't do so by choice, and the Replicants, with their predetermined "lifespans," are doomed creatures. But, as Tucker notes, unlike in classic noir, in Blade Runner, "The entire thematic foundation...is built around life and death—not constrained to simple mortality like in classic noirs, but expanded to examine the nature of life itself."

"The entire thematic foundation...is built around life and death—not constrained to simple mortality like in classic noirs, but expanded to examine the nature of life itself."

3. The detective and his code

Quoting from the text on noir, Tucker shines a light on the role of the detective within the genre, where, a little like Dante's Virgil, they act as a sort of tour guide of hell: “The private detective is midway between lawful society and the underworld, walking on the brink, sometimes unscrupulous but putting only himself at risk, fulfilling the requirements of his own code and of the genre as well.” As Tucker notes, Deckard might be a symbol of "law and order," but he himself has to be arrested in order to be forced to come in and see his own captain:

"As a blade runner, Deckard’s character is able to explore the ambiguous moral landscape of the story, just like the private detectives of classic noir," and it is noted that Ridley Scott himself compared Deckard to the most famous of all the film noir private detectives, Philip Marlowe:

It's almost impossible to imagine a world without the aesthetic of Blade Runner, and just as inconceivable that no one thought to combine the two essential American genres, noir and science-fiction, before Philip K. Dick and Ridley Scott. Furthermore, it is probably worth meditating on the fact that for most adults, 2017 seemed at one time not so long ago like a distant vista, full of impossible promises. And yet, here in that 'future,' we find the world to be not only oddly similar to the one we remember, but different in ways that are strange and disorienting.

The future is not made from shiny new parts, but cobbled together from the rusting hulls of infinite former presents.

Like in Blade Runner, or Terry Gilliam's Brazil, the future is not made from shiny new parts, but cobbled together from the rusting hulls of infinite former presents. And so, fittingly, in 2017, the future that seems to us the most true, the most representative of our collective mood, seems to be the one we find in the world of Blade Runner. And if movies are, on some profound, unspoken level, projections of the wishes and fears of the collective unconscious, then the worlds of Blade Runner, and now, Blade Runner 2049, must be the worlds we secretly believe we inhabit. Yet, even if these worlds might seem hopeless, there are still heroes there, fighting against the stacked deck, and against their better judgment, for some sense of right and wrong.

Which isn't much, but it's something, and if that's the case, then maybe there's hope for us, yet.

Source: Lessons from the Screenplay