5 Essential Tips for Crafting the Narrative in Your Documentary

If the story you end up telling is exactly as you had imagined, then you weren’t listening.

Constructing the narrative is the most important part of the documentary filmmaking process. It’s also the most challenging, as there is no script. There are endless ways to shape the story, and figuring out the puzzle can be simultaneously exhilarating and frustrating.

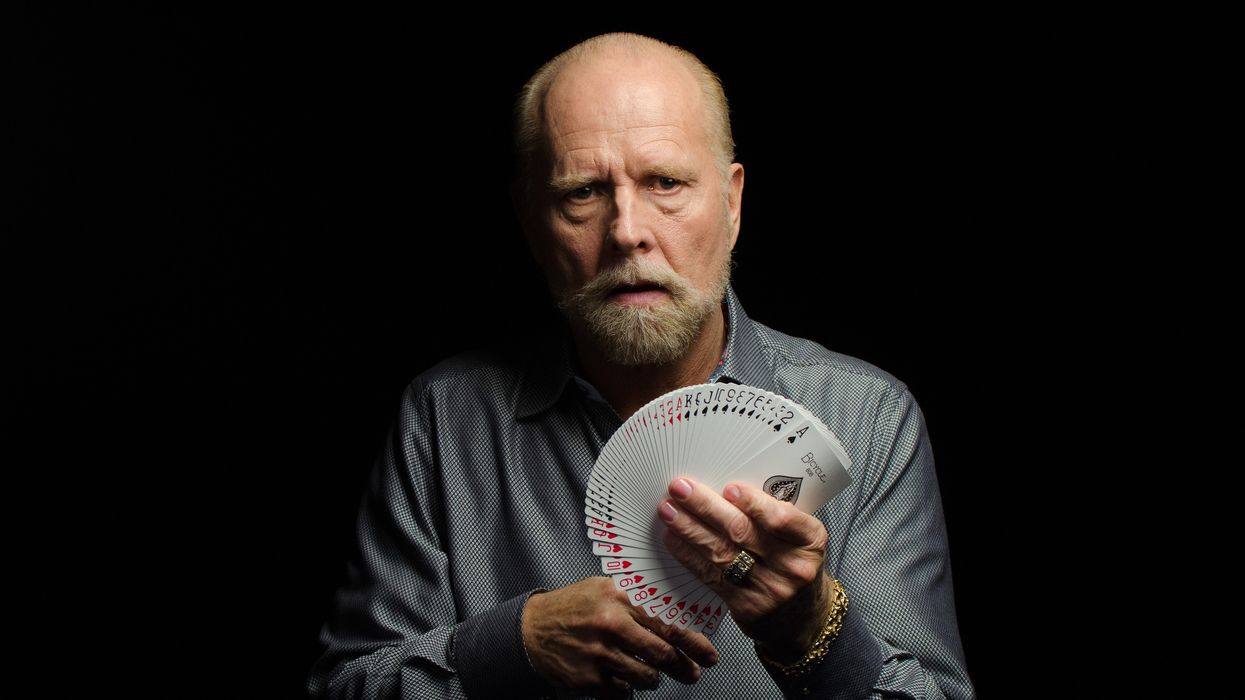

I’ve directed and produced two documentary features, and learned a lot about the writing process. My most recent film is the Sundance Selects documentary Dealt, which tells the story of sixty-two-year-old Richard Turner, who is one of the world’s greatest card magicians, who happens to be completely blind. The production of Dealt took several twists and turns, and challenged me on many levels. In particular, it taught me several lessons about story. I’d like to share with you that experience and five tips for crafting the best narrative in your documentary.

1. Listen

If the story you end up telling is exactly as you had imagined, then you weren’t listening. This is a critical concept to grasp, and takes discipline to apply. Documentaries deal with real life, which is complex and messy. When you start production, it’s tempting to let preconceived ideas and notions completely guide you. This can easily result in forcing a square peg into a round hole, or completely missing the mark. However, if you are disciplined to listen, then the best story will reveal itself. You might ask a question in an interview and the response illuminates a surprising path. Or you might stumble upon archival footage that reveals a pivotal moment in a character’s life. Or the story might change entirely before your eyes as you capture it with your lens. All three of these things happened while making Dealt. I thought the film was about one thing but—upon examining the pieces—realized there was a more fascinating story to share. You’ve probably heard other documentary filmmakers echo this same experience.

Now, I’m not saying you shouldn’t prepare an outline prior to production. You should certainly do that. After all, you need to know if there’s enough conflict and intrigue to support making the film. What I am saying is the final film should deviate from your outline. Focus on listening all the way to the end. Listen to what the story is telling you, and the film will be greater for it.

Using the mantra of "making a movie" will help you craft a richer story and create clarity.

2. You are making a movie, not a documentary

Michael Moore made this statement and it’s powerful. Think about it. People want to feel emotion when watching your film, not just learn information. You are a filmmaker, not someone laying out facts. Early into making Dealt, I found myself fixated on communicating details to the story and not the story itself. I realized this error only after my mindset changed: I focused on making a movie. I then felt more free to entertain and use the characters to propel the arc.

Yes, the genre is documentary but it’s still a movie. Using the mantra of “making a movie” will help you craft a richer story and create clarity. It will help you make cuts to your documentary. You’ll be able to spot unnecessary or force-fed information. You will have more focus on the arc of your characters and subject. I suggest you write on a piece of paper “I am making a movie, NOT a documentary” and put this on the wall wherever you edit, review footage, or brainstorm story structure. This will change your thought process, and will make your film more compelling. People want to watch a movie, so make one.

3. Don’t edit your own film

You want to avoid at all costs editing your own documentary—especially the first rough cut. This is a point I failed to adhere to in my first film. Hiring an editor has so many benefits beyond just saving you time. If you are the director or producer, you are in the weeds. You have a pulse on the story, but oftentimes your vision is a bit skewed. A good documentary editor will find crucial moments and create brilliant scenes that you likely would not have rendered. Doc editors are like writers, so find a good one and it will elevate your film. For Dealt, we hired a full time editor who assembled the first couple rough cuts. We communicated mostly via Google Hangout because we lived in different cities. It was liberating to provide direction, turn him loose to apply his ideas, and then we jointly reviewed the cuts. I know Dealt would not be the same without that editor and the ideas he brought to the table. I did eventually get my hands dirty in the edit room (more on that later), but that was only after he did a lot of the heavy lifting.

I strongly urge you to use whatever resources you have to hire an experienced documentary editor. If you can only afford to hire one for a few months, do it. If you are strapped for cash and must edit this yourself, I suggest you get a writing partner. That’s what I did for my first film when I was the primary editor. My writing partner sat in the edit room on a weekly basis, reviewed footage, and we bounced ideas off one another. In fact, I enjoyed that partnership so much that he and I worked together on Dealt. You should get an editor or writing partner if for no other reason than to keep yourself sane! No one should sit in a dark room by themselves for months on end.

It’s going to take longer than you think to find the narrative and shape it properly.

4. Think long term

Docs are a marathon, not a sprint. Don’t put pressure on yourself by setting an unrealistic completion date. You should definitely set milestones to keep you and your team accountable, but add contingency to your schedule. It’s going to take longer than you think to find the narrative and shape it properly. This is especially important if you adhere to tip #1 (listening). As previously mentioned, I realized mid-way through production on Dealt that there was a more powerful story to tell. The film at that point was mostly a past-tense biopic. The arc of the story was mostly what happened leading up to this point in the main character’s life. However, it wasn’t sitting right with me. I had reviewed a lot of the cinéma vérité we had filmed, and found it to be more interesting. I also sensed (from listening) that there was a present day conflict and story that was unfolding.

After considerable thought and a team meeting, we scrapped half the edit and reversed course. We decided to film for an additional full year. This also meant I needed to jump in the edit room because our main editor was no longer available. It all sounds crazy but it was the right move. The story we ended up telling has more weight and resonates with a greater audience. It was totally worth it. Your job is to tell the best story and often with documentaries it takes longer because you don’t have control. Be flexible and allow yourself the freedom to step back and really examine the characters, scenes, and the story arc. Think long term and you’ll save yourself stress.

5. Test screen early and often

Test screenings are so vital to documentary filmmaking, but it’s one of the hardest things to do. Why? Because it takes humility to accept critique. Who likes people poking holes in their work? No one. However, the goal is to make the best film you can, so test screen early and often. For my first documentary, I was very nervous for the first few test screenings. My producing partner encouraged me to do it and he was right. Although, it didn’t at first feel that way. I was embarrassed watching the cut and realizing, “That entire section needs to be cut”, or “That didn’t work at all”. Then, I learned to embrace it. I saw the film vastly improving from the feedback. It was exciting! It was so helpful and therapeutic opening the doors for other opinions to be heard.

Remember, you’re not making a film for yourself. Rather, you are making a film for everyone but yourself. For Dealt, we test screened about six times before locking it down. With all that said, my suggestion is to invite trusted filmmakers to screen your first cut. Pass out questionnaires and open up for a group discussion. Encourage people to speak their mind. It’s up to you to decipher what feedback is purposeful and what’s off base, but you should hear a consensus on a few main points. For each screening, go in with a mission to figure out one more piece to the narrative puzzle. Screen the film several times mixing in filmmakers and general audiences until you reach the story that resonates. Test screenings are part of the process to making your film great. Embrace it!

Documentaries are a great adventure, and shaping the story is at the heart of it all. There is no secret formula, but there are tools you can use to put the puzzle together. Within your subject is very likely a great story to be told. Be encouraged that you can do it. Keep exploring, refining your skills, and learning from those around you. I hope my experience with Dealt and these tips I’ve shared prove helpful in whatever is the next story you choose to tell.

Luke Korem’s documentary DEALT is now available on iTunes, Amazon, Hulu and more.