'Never Ask for Permission': Alexander Payne’s Seven-Step Filmmaking Crash Course

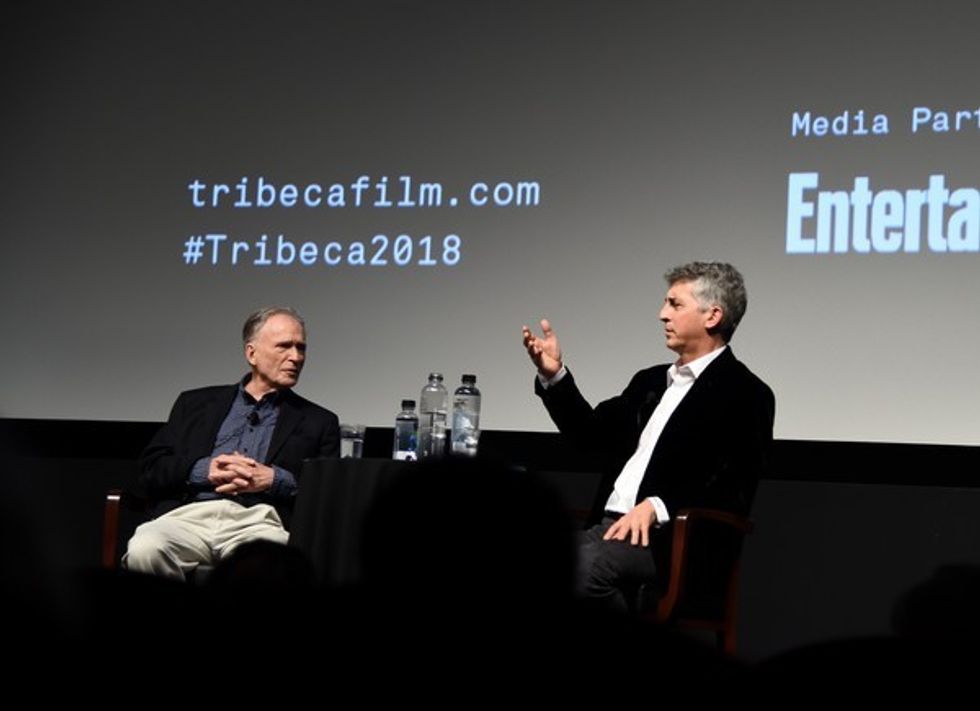

Alexander Payne stopped by Tribeca to reveal the highs (and lows) of running a film set.

Election, About Schmidt, Sideways, The Descendants, Nebraska.....each film was a success in its own right, both critical and popular, a mix of dry, satirical wit and humanistic insight. Each film came from the mind of Alexander Payne, the Oscar-winning writer/director/producer, and he shared his wisdom at the 2018 Tribeca Film Festival for a special conversation.

Onstage next to Payne was legendary TV host Dick Cavett, moderating the discussion. Both men were born in Nebraska and are fond of off-the-cuff humor. After some anecdotal palaver, their talk segued into great filmmaking advice, specifically, Payne’s bullet-point process for conceiving and executing an idea. No Film School was on the scene to learn more.

1. Be Open To Possibility

First and foremost, Payne encourages openness. Now age 57, he has made only seven feature films—a small number, as he describes it—but patience is part of his process. Often, that means waiting for the right idea. “I only want to speak when I have something to say,” Payne explained, almost apologetically, "and my number one job is being open: reading books, articles, screenplays, searching for ideas. Before I read Election (the novel on which the 1999 film is based), the last thing I wanted to do was a high school picture. God no. But then I did.”

Payne explained his approach to screenwriting with a tinge of contrition. “The old cliché is true: the script chooses you. I wish it happened more quickly, I’m not quick like Woody Allen, who has the discipline to keep cranking them out. I wish I could make films all the time...instead of being here today!”

2. Don’t Snooze & Lose

Payne was careful to distinguish patience from procrastination: openness doesn’t mean laziness. He advised his audience to keep an eye out for opportunities, and know when to recognize them. “You gotta strike while the iron’s hot,” he insisted. “Don’t wait around. I was gonna write to Marlon Brando [also from Omaha, Nebraska] but I never got around to it.”

“If you get these chances, don’t snooze and lose like I did."

Payne’s remorse showed. “I met Sidney Lumet, he said 'let’s get lunch in New York.' I never called, he died. Once I was in the bathroom peeing next to John Frankenheimer. I didn’t call him in time either, he died.”

Cavett chimed in: “Do you mind if I move our lunch forward?”

Payne laughed, then turned serious. “If you get these chances, don’t snooze and lose like I did. Man, what an asshole I am.” He gave a rueful laugh.

3. Savor What You Know

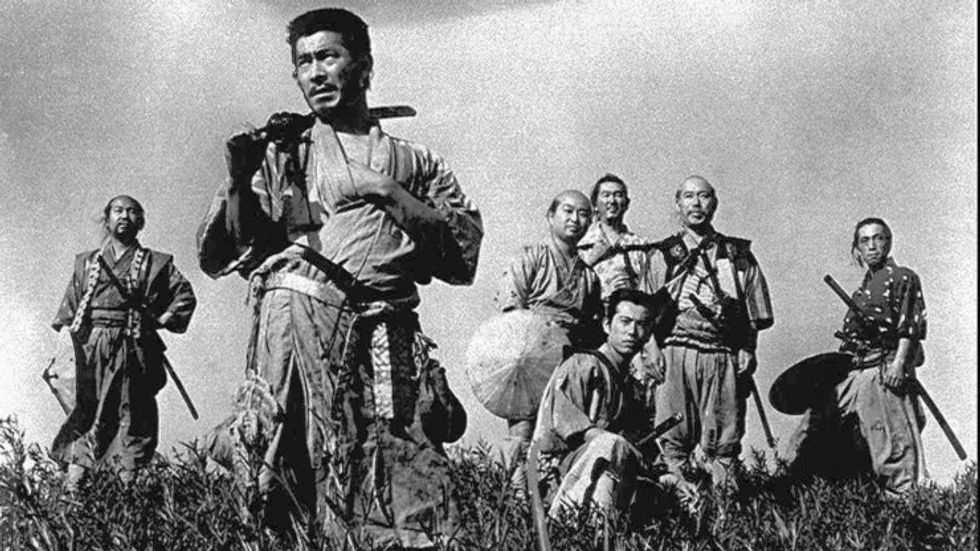

Payne’s inspirations shed light on his particular filmmaking style. A huge Akira Kurosawa buff, Payne cites Seven Samurai (1954) as his go-to answer for the dreaded ‘favorite movie’ question. Among other favorites he mentioned were Ernst Lubitsch’s To Be Or Not To Be (1942), Kurosawa’s Red Beard (1965), Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969), and Hal Ashby’s The Last Detail (1973).

“Writing and editing aren’t support skills, they are the job."

But perhaps his biggest inspiration has been his hometown of Omaha. Payne—who has already made four films-and counting based in Nebraska—loves to write from experience. “Writers often use where they grew up as fodder,” Payne avowed. “For me, Nebraska is something I can grasp, I can recreate Nebraskan behavior with some degree of verisimilitude. Even then, it’s ultimately mysterious, like trying to somehow unlock those smells from your childhood.”

Being able to evoke those experiences onscreen is an important part of the artistic process for Payne. “Cinema is this fantastic mirror. By making my own movies about what I know, it’s as though the people I knew in the course of my life finally matter. That’s why it’s important for national cinemas, for countries, to make their own movies and fight the hegemony of American cinema. You don’t need to see yourself literally, but you’ve gotta feel represented. I just like seeing the Midwest and those rhythms on film.”

4. Value Writing & Editing

An audience member asked Payne what side skills a director should have: writing, perhaps editing? Payne was quick to reply, “Writing and editing aren’t support skills, they are the job. You can’t become a director until you master the art of screenwriting. If you want to make narrative films, you’re gonna have to write for yourself. You’re making a film in your brain, and a screenplay is the written record of your imagination.”

“Making a film is like cooking eggs. You wanna make a perfect omelet, but sometimes you have to say ‘fuck it’ and make scrambled eggs."

According to Payne, writing and editing are two sides of a coin, and in order to be an auteur, you need chops for both. “It’s normal to overwrite. You can never foresee exactly what you’ll need to omit in the cutting room,” he explained. “Which is why it’s all about editing. The only reason I write and direct is to get material to edit. And editing is just the ongoing process of disguising how bad the film really is.”

The way Payne tells it, editing is a grueling slog, but it’s also the purest part of the storytelling process. It takes courage, especially when facing your ugly rough cut. “Your first cut will SUCK. It’s hideous, but every day you’re gonna go in the cutting room and make it suck less. Deciding what you do or don’t need feeds directly back into the writing process.”

5. Make Scrambled Eggs

If writing and editing are key, what about directing? Once again, Payne advises flexibility.

“Making a film is like cooking eggs,” he smiled. “You wanna make a perfect omelet, but sometimes you have to say ‘fuck it’ and make scrambled eggs. Make it as good as can be in the given moment.” He laughed, mind undoubtedly swirling with thoughts of his own screw-ups. “A movie set is full of people just trying to freak you out: ‘Oh, the actor is sick; oh, it’s gonna rain; oh, I had the keys in my left hand which screws up continuity…”

As Payne sees it, things will inevitably go wrong – so your best bet as director is to prepare for the worst. “Get as much coverage as possible, stock up on material that you can cut away to when needed,” he cautioned. “And trust your collaborators: you made them part of your team because you liked their instincts. Let them help you.”

“I just had a movie that tanked!”

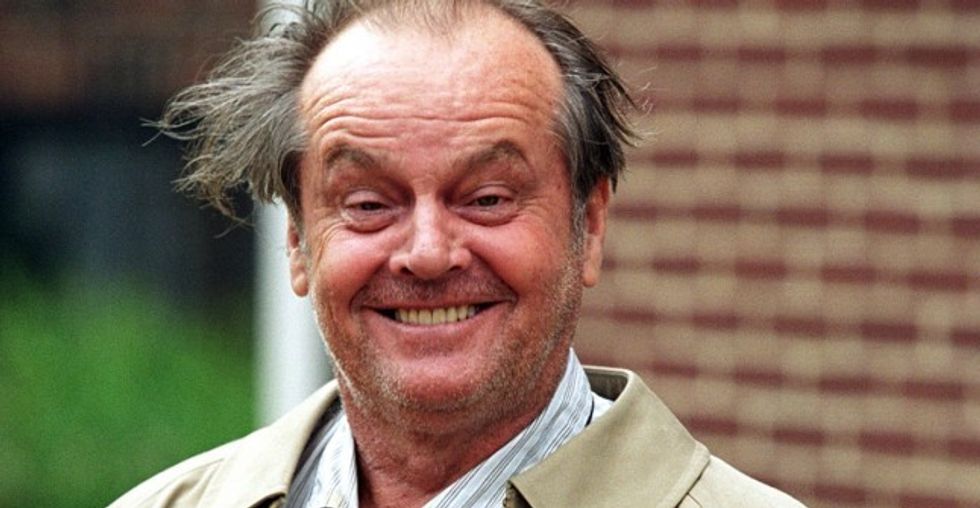

Payne cites Jack Nicholson as an ideal collaborator. “Nicholson made me a better director,” Payne enthused. “He’s so good—he’s like a Ferrari—he will do exactly what you say.” Payne laughed, miming his grip on an imaginary steering wheel, then losing control. “I would say something and he’d do it with exact precision, then I’d realize that I’d steered him a little too far to one side.”

In other words, Payne advised controlling less and listening more. And, perhaps most importantly, he emphasized the importance of inspiration.

“When you make a film, you’re putting time in a bottle. You’re trying to capture the zeitgeist, the essence of the story you’re trying to tell. And if you’ve opened yourself to inspiration—and if you stay open throughout production—your ideas can evolve into something even richer. If you’re open as a director, the winds of history will blow through you and your set, all the molecules of that moment will be within reach. If you just stay open when you turn on your camera, you’ll get what you need.”

6. Find Joy in Your Pain

Payne’s enthusiasm was palpable—but even so, he reminded his eager listeners to take his advice with a grain of salt. “I just had a movie that tanked!” He laughed at himself, referring to his recent box-office disappointment, Downsizing. This ambitious film was a tough blow for Payne: it grossed only $55 million against its $68 million budget. He described making Downsizing as “the most agonizing process, nothing was easy about that thing. The script was hard, financing was nearly impossible, the production schedule huge and editing was a toughie. But it was still made with joy.”

"You are your voice. You don’t look for it, you don’t find it, You ARE it."

The crowd wasn’t satisfied by Payne’s bittersweet outlook. Someone asked, “Why didn’t Downsizing click?” Payne frowned, thinking hard. “One answer may be that we were a little bit greedy as screenwriters. This was a big idea that could have fuelled a TV series, and we tried to cram it into two hours. Some of the narrative turns were too hairpin, maybe the protagonist was too passive. Who the hell knows… NEXT.”

7. Don’t Ask Permission

Given this recent disappointment, Payne may be in a world of pain—but he doesn’t show it. Like many accomplished artists, he’s not afraid to be self-critical and he’s not afraid to move on. Regardless of how cautious studios may be with the scale of his next budget, you can be sure he’s working on his next passion project. In fact, this kind of forward-thinking, he reasons, is something all filmmakers should emulate.

“The key is never to look to others for permission,” he asserted. “Do it yourself, at whatever level you currently find yourself. You can buy a great camera for cheap, get Avid on your computer, and distribute your work on YouTube. You are your voice. You don’t look for it, you don’t find it, You ARE it. So just do it. Get out of here! Start making a film.”