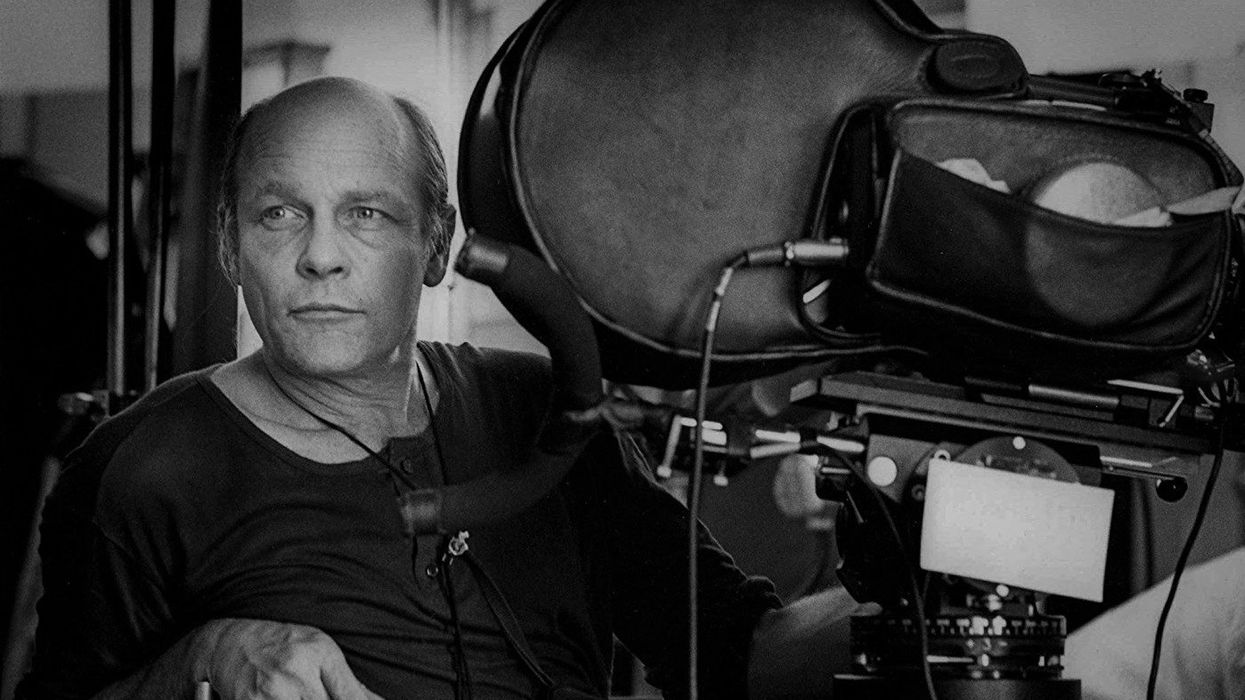

'Master of Light', DP Robby Müller, Passes Away at 78

The late cinematographer is known for his inspiring collaborations with directors like Jim Jarmusch, Wim Wenders, and Lars von Trier.

For a cinematographer, the frame is their canvas and light is their paint. So, when a DP receives a nickname like the "Master of Light," like Robby Müller, you know that it means something significant about their capabilities as an artist and visual storyteller. Perhaps that's why today's news of the Dutch cinematographer's death has rocked the filmmaking community to its core because we lost not only one of the most influential image makers in the industry but an unquestionable master of the craft, as well.

In 1962, Müller studied film at the Netherlands Film Academy, helming the camera on several shorts along the way. However, it wasn't until 1970 that he was able to land his first feature film gig, Summer in the City, a project that introduced him to frequent collaborator Wim Wenders. He went on to work with talented directors like Jim Jarmusch (Down by Law, Mystery Train, Coffee and Cigarettes) and Lars von Trier (Breaking the Waves, Dancer in the Dark).

His longstanding creative relationships with some of the most iconic art house directors are no doubt testaments to not only Müller's talent as a cinematographer but also his ability to do so much with very little. Though Müller went on to do some (kind of) mainstream work later on in his career, he was very much a cinematographer with an independent spirit. Explaining his contribution to Dogme 95, he was once quoted as saying,

We had nothing. I was not frightened to shoot a complete film with one lamp. Or no light at all. As people dare to do it and take the consequences of it, they will find the light.

\u201cWe have lost the remarkable, brilliant & irreplaceable Robby M\u00fcller. I love him so very much. He taught me so many things, & without him, I don't think I would know anything about filmmaking. R.I.P. my dear friend Robby #RobbyM\u00fcller\u201d— Jim Jarmusch (@Jim Jarmusch) 1530716891

His later work, though, was always left with his unique signature. There were countless films made in L.A. during the 1980s, but they could never compare to the L.A. Müller captured with his camera during that time. Films like To Live and Die in L.A., Repo Man, and Barfly all represented Los Angeles not as the fast-paced beach party for aspiring young professionals in convertibles, but as a tough, beautifully bleak city that was being torn apart from the inside by crime and violence—an L.A. in which the neon signs were made to match its sunsets.

Though it had been nearly two decades since he worked on a feature film prior to his death, Müller's absence will not only be felt by fans, admirers, and the renown filmmakers he worked with but also by cinema as a whole, both present and future.