29 Cameras and 203 Hours of Footage Later, This Haunting Movie Exists

Anthropocene: The Human Epoch directors and cinematographers unpack the ambitious scale of the visually-stunning and perennially haunting project.

It's fitting that Anthropocene: The Human Epoch, a film that attempts to convey the massive impact of humanity on the earth's landscapes, would require such a large-scale production. The film's three directors — Jennifer Baichwal (documentarian), Nicholas de Pencier (cinematographer), and Edward Burtynsky (photographer) —filmed in 20 countries and 43 locations over the course of five years. Their 29 cameras captured more than 50 terabytes of footage, totaling over 203 hours and ten different codecs.

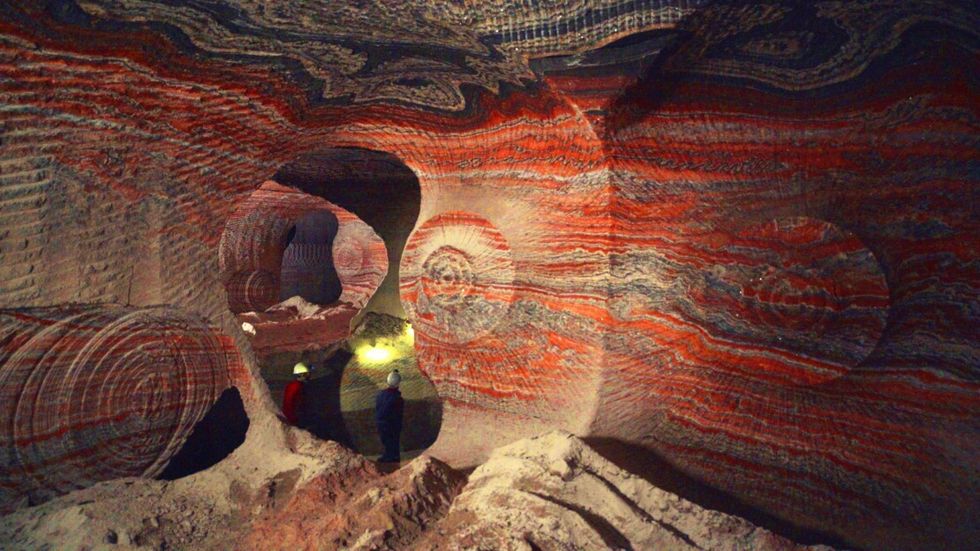

The result is a haunting overview of the myriad ways in which humanity has dominated, and effectively re-engineered, our planet. It's one thing to know, intellectually, that 75 percent of non-ice-covered land is occupied by humans. Or that 85 percent of forests have been cleared or degraded through human use, as narrator Alicia Vikander tells us in the film. It's another thing entirely to be cinematically immersed in that devastation.

Anthropocene travels to the closed city of Norilsk in Russia, one of the most polluted places on earth; to the concrete seawalls of China, which now covers the majority of the mainland coast; to rural Germany, home to the largest terrestrial machines ever built. The filmmakers evoke the essence of these places with a combination of aerial cinematography, wide-lens still frames, and on-the-ground stories that follow the people who live and work in these environments.

No Film School sat down with Baichwal, de Pencier, and Burtynsky to discuss their ambitious project, why the idea of the auteur is bogus, and more.

"The scale of it was so large and ambitious—to go all around the world in really challenging environments, taking the best cameras and biggest technology."

No Film School: You three have been working together for many years. I'd love to hear about your backgrounds, and how you came together to make films in the first place.

Jennifer Baichwal: To start, we never went to film school. None of us!

We've been making films together for 25 years. I was an academic doing a degree in philosophy and theology. I just decided to make documentary films, and I learned by doing.

I teach now sometimes, and what I teach is this: "Don't listen to me. Don't think that I have some kind of fount of wisdom where I'm gonna tell you how to [make movies]. You have to figure out for yourself."

I just hate this "sage on the stage" masterclass bullshit that happens so often in this industry. I get asked to do that all the time. I say, "I'm not doing a master class, 'cause I'm not a master. I'm a practitioner."

NFS: How do you navigate a film with three directors, in terms of division of responsibility and collaboration?

Edward Burtynsky: For Anthropocene, all three of us -- at the very beginning -- came up with the concepts, decided on the locations, and worked on fundraising together. The whole project was something from the very beginning that we collaborated on all the way through. That includes a museum show that's now traveling in Bologna, Italy.

Nicholas de Pencier: I don't think we could've just started this film not knowing each other and not having previously worked together. In a way, we built up to this film. The scale of it was so large and ambitious—to go all around the world in really challenging environments, taking the best cameras and biggest technology.

"In film, there's this emphasis on individual authorship—someone has a vision. I take exception to that. I think it's arrogant."

These environments are so jaw-dropping in terms of their scale. It's really hard to figure out, "How are we going to convey this place?" Edward, in his photography, is the master of finding a comprehensive view — a really large-scale image that tells the story of a place. So, sometimes, he might be looking for that while Jennifer and I are being more "classic documentary" — going and trying to find narratives on that ground that are suggested in the big scale, but that you can tease out and follow to an extent with film.

It was a very collaborative process and we would divide and conquer according to our competencies and inspirations in the moment.

Baichwal: I mean, film is a collaborative medium. It has to be. It's like this quote from Walker Murch, about The Conversation: "The director is the immune system of the film, letting in everything that makes it stronger and keeping out things that make it weaker." I like that analogy because the immune system is a whole group of things working together.

In film, there's this emphasis on individual authorship. Someone has a vision. I take exception to that. I think it's arrogant. There are a lot of things that come together to make a film work.

NFS: Jennifer, when you and Nick follow the documentary elements on the ground, what is your process?

Baichwal: We have no script for our films. It is a very deliberate, philosophical stance that we've had working together since the beginning. You can't script reality. If you're not open to what is happening in front of you — because you think you need something to happen — you're not gonna see what is really happening around you. So, we're very open with the way that we shoot. We enter into these contexts with great humility and try to convey the truth that that context is telling us.

Consequentially, we have tons of footage. Often, there's a real forensic mystery story of putting it together in the editing room. Our longtime editor for all three films, Roland Schlimme, and I basically go into a room for a year and just sift through everything and try to figure out the rhythm of the story.

"We have tons of footage. There's a real forensic mystery story of putting it together in the editing room."

NFS: If the editing process was a year, how long was production itself?

Baichwal: Five years.

The first year is really laying out the template of what we want to do. At the same time, we're going out there and putting out applications for money and grants and fundraising to make the film happen. Year three and four become the heavy shooting years. And then the fifth year, it's edit, and then release.

As you can imagine, working with a photographer [like Burtynsky], color correction is a painstaking process. Nick is mostly in the trenches there.

We also spend a lot of time on post-production sound, because it's such a crucial element of the experience. We do experiential filmmaking, after all. We do really long sound mixes, but the sound design starts way before that.

NFS: I was thinking about the sound while watching this film. On set, I'm sure many of the locations are full of industrial noise. I can imagine it must have been difficult to parse out what was most pertinent to the narrative.

de Pencier: That's so important with this kind of filmmaking. Our film isn't expositional, with talking heads and information, but is to be experiential. The aural environment is crucial. I do almost all the location sound recording when we're [on location]. I consider that part of my practice as a cinematographer. I really enjoy the challenge. I want to give the sound editors a [recording] that's based in the reality of the place — that really takes you there. In this case, we were also traveling with 360 DVR cameras and technology, so we also got the ambisonic sound. These environments are so immersive. You have to feel like you're in the middle of them, and sound does that.

"These environments are so immersive. You have to feel like you're in the middle of them, and sound does that."

NFS: Which cameras and lenses did you use, and why did you make those decisions?

de Pencier: Every time we start a new film, we say, "Okay, we're only using this one camera!" And it never works. Reality is messy! That would be a good T-shirt for documentarians.

The main unit camera was ARRI Amira, which is the same chip as the Alexa. It's what we're used to seeing in a lot of Hollywood films. I think ARRI was really smart in taking that technology and putting it back in a single-operator camera. All the buttons are where I'm used to them from years of HD cams and DV cams and Beta cams.

The cinema cameras are really challenging for following the action. They [require] a whole camera department swarming around and changing filters. But we weren't always together in the locations.

The drone we used was the original Epic, when it was brand-new technology. It's a 5K, big-chip camera. It has now become our main drone camera. It was actually was just upgraded—the sensor and body.

So, there's a range of formats. Thank goodness that there are platforms in the post-production world that mostly are agnostic. You can even massage in a tiny bit of GoPro or some smaller cameras [into a sequence] because it's the only way to get that shot. It's important to be able to physically put a camera somewhere where you can't get the big cameras.

Baichwal: I have some stats for you. We had 50.77 terabytes of raw footage. 202 hours and 57 minutes of material. 43 locations, 20 countries, six of seven continents. The entire film was carbon-offset. Six rafters, 10 Kodaks, 29 cameras. Filmed over four years, two months, and 22 days.

Burtynsky: 29 different cameras? [Laughs]

NFS: How do you, Edward and Nick, work together to tackle a given location, with your different specialties in cinematography?

Burtynsky: The thing that I've been doing in my photography from the get-go is to fit a large human system on the planet within one frame. Whether it's a big quarry, or a big mine, or deforestation, or an urban setting, I'm trying to capture it in a single frame. I shoot very high resolution. In the past, I had a big 8x10 camera with film, and then I went to a high-resolution medium format camera, 100-megapixels.

The crossovers happen based on light, conditions, situations, the difficulty of getting there, how much time we have with the place. Each situation calls for being very flexible. Sometimes we come together and shoot, 'cause I'm waiting for light, and Nick's swapping out the film camera with my stills camera.

"In my photography, I fit a large human system on the planet within one frame."

On location, Nick and Jen will go off and start thinking about the human story, while I capture these large-scale images. Then, we might talk about bringing the drone to capture more. In the evening, dinners would be kind of sharing notes and seeing what each other's done. So I'm finding the large, overriding images that show scale -- and Nick and Jennifer are bringing humans into the film. This allows the viewer to relate to somebody who works in that environment and how they think and feel about it and what they have to say.

NFS: I really appreciated the human element of this film. There was a version of this film where you didn't do that. It would have been visually stunning, but it wouldn't have had the same emotional impact.

Baichwal: It's a huge, very important part of our films. That large scale has to be offset by an intimate moment.

You know, it's not like we cast people before we go in there. Like I said before, we don't have a script. We are open. For example, we were in Norilsk [in Russia], and these three women were sitting, having their coffee break. I wanted to talk to them. But we got in deep shit for talking to those women. We were actually detained or arrested. But they were fascinating, these women. And without them, that whole place becomes incomprehensible.

NFS: How did you decide where to go, and then get access to those places? Some of these locations are very remote.

de Pencier: We tend to be very persistent. The first response we got from Russia [about Norilsk] was, "No, that's not possible." And then we just kept looking at any potential connection that we had. It was just persistence.

Baichwal: Some places we did not get to, though. We wanted to go to the Grasberg Mine, and we tried to get into this mine in New Guinea, right? That was just a "no." If you look at it, it's just unbelievable. It's like a hole on the top of a mountain.

"You feel like you have this unconscious ocean of preparation, but nothing can ever prepare you for the experience of being there."

I also wanted to go to the Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, which are basically human-made islands. They used to be coral reefs that they've put sand on. They've created these islands as a strategic military place. But our China producer said we'd all be killed if we went there. So, he wouldn't take us.

de Pencier: It's a contested area that China's trying to create. It's a strong position within the South China Sea, right in the middle of all the main ship traffic. A lot of other countries don't like what they're doing there. So, it's a really tense moment. We couldn't go.

NFS: Was there ever a situation where you were really surprised by what you saw?

de Pencier: Always! It's a wonderful privilege to be able to do this work and to go to these places that are so rarely visited. In a way, because of all the research, you feel like you have this unconscious ocean of preparation, but nothing can ever prepare you for the experience of being there.

When I'm on location, time is not linear. The camera's rolling and all of the months and even years of intentionality, of dreaming of what this would be like, is actually becoming manifest. It's the most ecstatic moment of filmmaking. I live for these moments.

And it can't help but change you. I hope that that informs the filmmaking. I hope we're bringing back our subjective experience as authentically as we can in these images and sound files, and putting it together so that other people can share these moments.

Burtynsky: For me, the most powerful moment was filming the 11 piles of tusks. They opened up these containers and out fall all these tusks. You get hit with the smell of death. You can just see where all the chainsaws had cut the tusks off. You know, these are the tusks of almost 10,000 elephants. When poachers go in and see a herd, they're looking for the biggest bull elephant with the largest tusks -- 'cause that's gonna have the biggest yield. That's the one they shoot. These elephants are called super tuskers and there's only 25 of them left in the world.

There's a human senselessness about them being killed not for meat or survival. They're being killed for the money they can get for the tusks. That was heart wrenching to think that we can almost be bringing at a species that magnificent to extinction for tchotchkes. There's something so wrong with that.

This ended up also being the footage that opened and closed the film. It's one of the most powerful stories throughout the film about extinction. For me, that was the most emotionally challenging thing that occurred in the making of this film.