My Wife and I Made a 3000 Shot Feature Film By Ourselves (and You Can Too)

Think you have what it takes to make a feature film? Let this story guide you!

As I write this, we are just hours removed from the Golden Globes, where Ricky Gervais eviscerated the state of the Hollywood film industry, chastising it for making “awful” films, leaning on, “remakes and sequels,” which he termed as “lazy.”

One movie that certainly wasn’t lazy was ours. A 3000-plus shot, dark, cerebral, psychological thriller titled, Dangerous to Know, that was made entirely (pre-production-and post) by just my wife, Jennifer, and me.

That’s it.

They say that if you want to change in the world, you need to be the change.

Like everyone else, we know that there’s been a stagnation in Hollywood film recently, which seems almost certainly to be the result of the adoption of the industry’s rigid 90-minute, three-act structure, which has led to overly produced, “phone it in” films, where often the music, sound design, and cinematography are forgettable.

Amazingly, despite these challenges, talented young and first time Hollywood filmmakers continue, year after year, to defy these rigid parameters and make truly decent films...but one has to ask: “What could they do if their imaginations were set free?”

Thanks to my background as a digital technology expert and futurist, and leveraging what I knew about the underpinnings of the filmmaking hardware and software available at reasonable costs, plus online resources and communities like No Film School, I was able to set my own imagination free and film a 3000-plus shot feature film...and it looks, sounds, and feels incredible.

I’m thrilled to be able to share what I’ve learned, and hopefully inspire the vibrant, open-minded filmmaking community that provided me with so much inspiration at the start, to go out and replicate what I’ve done (with technology that is already vastly better than what I had access to when we started filming in 2016).

How this all came about

Dangerous to Know is a film that looks as good or better than the Hollywood big-budget productions, but it was made with virtually no-budget, funded completely by the money I’d earned for my Kindle series of bestselling novels.

The story behind it is one that most aspiring filmmakers would understand well: I needed access.

My dream, since I was six years old, was to one day be a novelist and have my stories adapted for film. Like a lot of people, even much of my own fervent fan base, I assumed that if my book was at the top of the charts for a sustained period of time, that Hollywood would jump at the chance to adapt it.

I was wrong.

Although it’s true that Management 360 did call and asked me to write scripts for the first two novels in my Post-Human series, it was explained to me that the scripts would need to somehow catch the attention of a major, established talent, if they had any hope of being made.

Essentially, if Cruise, DiCaprio, or Spielberg didn’t call me, I was probably out of luck.

And even if a near miracle did occur and one of the major, established talents did take an interest in my series, I was still going to have to accept that, as the process moved along, I’d lose more and more control until eventually, I had no say at all... “But hey, you’ll make a ton of money, so who cares?”

Writers and directors will understand me when I say: I care.

Background

It hadn’t occurred to me previously to actually make a film myself. Like most people, when I saw the sheer scale (in regards to both money and people power, of Hollywood film productions), I assumed that making a film took years of dedicated training and that everyone who was working on a film set was doing a job that few others could master.

It wasn’t until I explored the idea of partnering with a local production company in Vancouver to make a five-minute Proof-of-Concept short film for my Post-Human series that I finally experienced what goes on, from the ground up, in typical film production.

My background as a technologist kicked into gear immediately upon reading the proposed budget’s breakdown of $25K for only a one day shoot (minus the VFX!) and learning that, among other ridiculous oddities, “professional” digital film cameras were $1000 just to rent for a day! That got me interested...really interested.

You see, in researching my Post-Human series, I’d become an expert on information technology and AI, and I knew that the price performance of digital technology nearly doubles, year over year.

In laymen’s terms, what that means is that a computer, a phone, or a digital film camera, should have its cost cut in half, roughly every eighteen months, and we see evidence of this in the progression of things like tablets and laptops.

I did a little research and discovered that the first digital film cameras to be used on a major production were made by George Lucas’s team, and debuted to other major directors in 2002. And although the early period of digital, HD film was unquestionably inferior in overall quality to traditional film in the early part of that decade, leading to a slow adoption for the first few years, there was a giant leap forward between 2009 and 2014, when the ratio of digital vs. film in Hollywood productions went from just 10% to 90%, forcing Kodak to announce that they were ceasing production on film stock.

This made a lot of sense to a technologist. HD had been replaced by 4K and 6K sensors by then, digital post-production tools were easier to use than literally cutting films together in the editing room, and they were far superior in quality as well.

But there was a problem: The fear of change.

Thinking Outside the Box

It’s become a cliché in business, but the term “think outside the box” was first coined by Marshal McLuhan, a media theorist from the University of Toronto, who explained it as part of a larger argument about people’s conception of the future. He wrote that people “see the future through the flavor of the most recent past,” and he called this the “rearview mirror society.”

Think about the first cars...they were “horseless carriages.” They didn’t need to look exactly like horse carriages, but it was the easiest way to explain the technology to people who’d been used to their horse and buggy. It made it less frightening.

The same thing occurred in Hollywood. The first digital film cameras had to be made to look just like the old film cameras, or else cinematographers refused to use them.

Even DSLR cameras look like the old point and shoot film cameras of thirty years ago, even though there’s no practical reason for it.

And because of this “rearview mirror” mentality, it made sense that digital film cameras would be treated exactly like the old film cameras (a century-old technology by the time they were replaced) with a generally fixed cost, since they weren’t digital, and therefore wouldn’t double in capability or price performance.

A great example to illustrate the point: Aspiring Filmmakers should go to YouTube and watch David Fincher’s BTS on Zodiac, a film he made in 2007 with a digital film camera and edited on iMacs and MacBook Pros.

Fincher is commonly thought of at the best technical filmmaker on Earth and was an early adopter of digital technology. Zodiac is available on numerous streaming sites.

Watch it.

Ask yourself: Do the quality of the images not hold up?

And when you come to the obvious conclusion, then ask yourself a second question: Would you choose to make your movie with his 2007 “professional” technology? MacBook Pros circa 2007, iMacs circa 2007, Final Cut Pro circa 2007?

Or would you choose something like the Blackmagic Pocket Cinema Camera 4K, or the Sony A7s II or A7 III? Would you choose the late 2019 MacBook Pro, a brand new Mac Pro? An iMac Pro? DaVinci Resolve 16?

Which do you think David Fincher would choose, had he been given the chance to reach into the future and grab the gear?

This leads us to the opportunity for a technologist/filmmaker.

The Revelation

I quickly realized that I needed to take control of my proof-of-concept short film for Post-Human, lest we spend a ton of money and not get much quality in return. I bought myself a BMPCC for less than the cost of one day of renting one of the “pro” cameras with similar specs, and we filmed the entire thing in under three hours.

The film had over a million views on Vimeo and led to me being asked to write the scripts for the Post-Human series. It also led to a lot of media coverage, and Blackmagic Design even asked to use the film at camera expos they were attending.

Overall, not a bad result for my first short film.

But the real value was in the insight I’d gained.

Simply put, I now realized that there was nothing stopping me from scaling up the extraordinarily stripped-down, fundamental way I was filming, to actually make an entire feature film.

Wow.

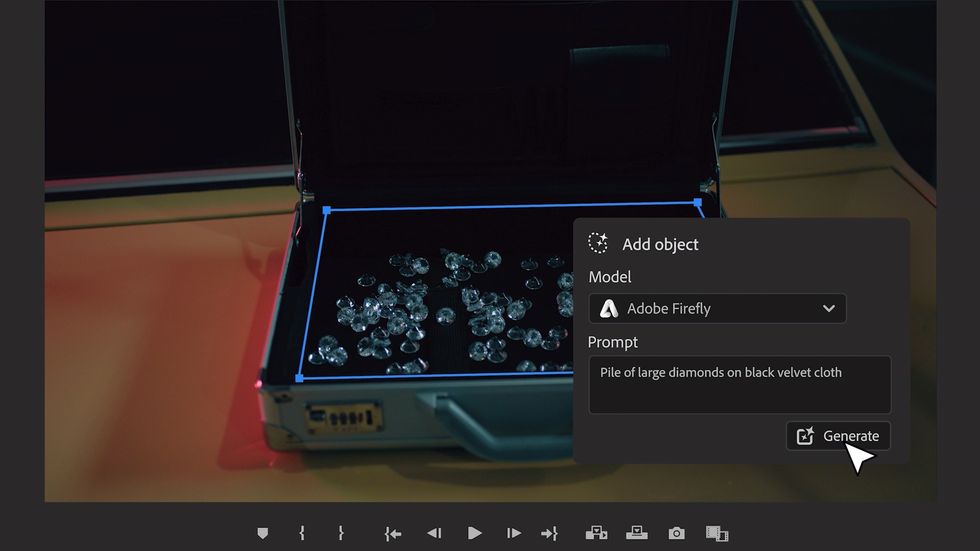

The only caveat was that I couldn’t make a VFX heavy science fiction film or a period piece—anything that required lots of VFX, sets, or costumes was still not affordable for a no-budget filmmaker.

However, if I wrote a story and set it in the present, and I used real locations, our own clothes for the costumes, and rented or borrowed vehicles, I knew I could make a film with absolutely no compromise whatsoever. The technology would make it possible for my wife and I to make up the entirety of the production crew, and we’d learned from doing the post-production on my short film, that we could do the post entirely on our own.

The Story

I’m personally a fan of David Fincher’s filmmaking, and The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo was a big influence on the tone and overall look and feel of the movie I wanted to make.

I’m also an admirer of Quentin Tarantino’s ability to construct scenes in which the mere circumstances in which the characters find themselves, and clever twists and turns in the dialogue, leave the audience gripped even more so than the most outlandish car chases or superhero smash-ups.

And since we were making a no-budget feature film with the goal of making a film that looked like it cost $65 million, being able to write gripping scenes without resorting to car crashes or heavy VFX, was a must!

So I settled on the psychological thriller genre, and my first idea was to build a film around Bridget Graham, the lead actress from my short film. Bridget has a certain je n'est ce quoi quality that convinced me that she had star power, and I felt I could leverage the fact that she’d been typecast by Hollywood as the “hot girl” to my advantage, and offer her the chance to play a gritty, conflicted, dangerously disturbed character, and allow her to prove to the world what she could do. She jumped at the chance.

Once I knew she was on board, I went to work constructing a plot. I’m very lucky in this regard. My wife says that I “think in plot,” and I agree. While most writers struggle to construct plots, I really don’t, and in fact, have the problem of having more plots written in my notes than I have time to write as novels and films.

It only took me about a half hours of brainstorming to come up with my eureka moment, and when I had it, I knew I had the movie. I double-checked with my wife, Jennifer, who isn’t a writer, but I trust her taste. She often goes for walks with me and lets me use her as a sounding board when I’m creating plots, and I always know I have something special when she gets that look in her eye—her breath catches—and she says, emphatically, “Yes!”

And oh, man, I cannot wait for the world to see what we have in store for them in this one!

Our Equipment

In 2016, the first affordable singlet stabilizer came online, the CameTV. It was sufficiently powerful enough to hold our camera set up, and it was our only stabilizer for the first half of the shoot, which started in early May that year.

Later in the summer, we were able to upgrade to the CameTV Optimus, which was much improved in all respects, and its reliability made our work go much faster.

We chose the Blackmagic Production 4K and the Sony A7s II as our main cameras. The Sony was chosen for its incredible (and still class-leading) lowlight capability. Since a lot of the movie takes place at night, I knew I needed a camera that wouldn’t require the absurd lighting setups that Hollywood generally employs. This had the added bonus of giving our film a far more realistic and disturbing nighttime look, allowing actors to literally disappear into darkness at times, just like in the real world...no need to suspend disbelief and pretend forests are lit like baseball stadiums with mysterious fogs floating about. ;)

We used the industry-standard Sennheiser MKH416 microphone and recorded on the day sound with a Zoom H4n and used a RØDE shotgun mic mounted on the camera as well. Most of our sound was rebuilt, however, in post-production, which we completed in a home studio that I decked out for ADR, and later for Foley.

Although the original plan was to finish filming in the early fall of 2016, our lead male actor, Andrew Robert Wilson, was seriously hurt in an accident during a break in filming when he was back home in Vancouver. The injuries were so severe that it was impossible to film again until he healed, so that didn’t occur until the following May of 2017. By then the Sony A6500 had come online, and we used that camera, and its reliable focus, to get even more dynamic shots during our final days of filming (although the Sony A7s II remained our main camera).

Finally, the Zhiyun Crane 2 came online, and we used that as a stabilizer for final inserts and reshoots that we did throughout 2018, parallel to our work on post-production.

Post-Production

My wife, Jennifer, and I did everything.

We recorded the ADR with the actors, we recorded the Foley, and we even took the DaVinci Resolve 15 Fairlight course to learn to be accredited sound designers for our film. We mixed everything ourselves, with Jenny targeting the acquisition of sound effects and soundscapes, while I focused on the dialogue and mixing everything together for the final mix.

Color grading for the over 3000 shots was done entirely by Jenny. She learned it from the ground up, utilizing YouTube tutorials and resources like No Film School, and became an incredibly proficient colorist as a result. We went for a hybrid of David Fincher’s, sleek noir aesthetic, highlighting greens and yellows, and Tarantino’s film-look, which was accomplished by using FilmConvert and selecting a similar “film stock.”

I edited the film myself, which was a grueling process, since we did a lot of takes, and we didn’t have anyone who could put together rough edits as we went. With a film that has over 3000 shots, and considering we averaged about six takes per shot, sifting through the footage was a process that took more than a year. It was hampered by the available desktop hardware in 2016 and the first half of 2017, but a much-needed upgrade finally arrived, and that unlocked the potential of the software we used for all of our post-production, which was various iterations of DaVinci Resolve. That, in addition to me being lucky enough to have a photographic memory, sped the process along, and the final 80% of the editing was done in just a few months.

Finally, the music.

That, in itself, is an insane story.

Originally, I was going to hire a composer, but once the visual edits to the film were locked in, I broached the subject with my wife and suggested that I had a theory.

By that point, she was used to me having insane ideas about reinventing the wheel, so she just rolled her eyes and gave me a half-hour to prove my point.

The theory was this: given what I knew about information tech, software and AI, I felt sure that there would be more than enough programs available for me to get the exact music I wanted...if I could compose it myself.

I’d listened to music that was “placeholder” music from various films for months by that point and had been inspired by Hans Zimmer, Carpenter Brut, Trent Reznor, and Atticus Ross, and John Williams. And when people hear the score, or if they simply listen to the score in the clips that are available on Dangerous to Know’s Kickstarter page, they’ll hear those influences.

The really strange thing? I had no musical experience.

All I can say is that a keyboard makes a lot of sense to me, musical notes make sense, and I found as soon as I started experimenting on my iPad Pro, which was connected to my iMac and Logic Pro (and eventually various plugins), that I could begin to tell stories musically.

It was a magical experience. It was a whole new dimension in which I could express character, relationships, circumstances, and tensions. I’m so grateful for that insight and that experience.

Even crazier? When I returned to my wife thirty minutes later, I played her a little piece and saw that look in her eyes—her breath caught—and then she said, emphatically, “Yes!”

That exact piece—not a recreation—opens the movie, and you can watch it in Extended Clip 1 from the film on my Kickstarter page.

Results

The film is currently on Kickstarter until January 14th, now in its final week, raising funds for distribution. It caught the attention of the creator and director of Netflix’s The Haunting of Hill House, Mike Flanagan, who very generously backed the project and wrote a beautiful letter of support and encouragement for Jenny and I.

It has the best rewards packages I’ve ever seen, which stem from the fact that I’m a novelist, so there’s a novel version of the story, a graphic novel version (also done by me), an audiobook version, the soundtrack, and even an entire novel for fans of my Post-Human series. We also have chances to get your name in the credits, get a digital copy of the movie itself, become a producer or associate producer or even an Executive producer, and even more.

Or, backers can just pledge $1 Canadian (roughly 75 cents USD) to show support, earn a heartfelt thank you, and follow along as we try to change film history.

Jenny and I have only screened the movie for a small handful of people, but, so far, the reactions have been exactly what we wanted—but beyond what we could’ve dared dream possible before we began. We’ve really pulled this off...and we’ll get to show the world soon.

We’ll be screening it for an audience in the very near future, and finally allowing Hollywood execs to see it too.

Conclusion

It’s possible.

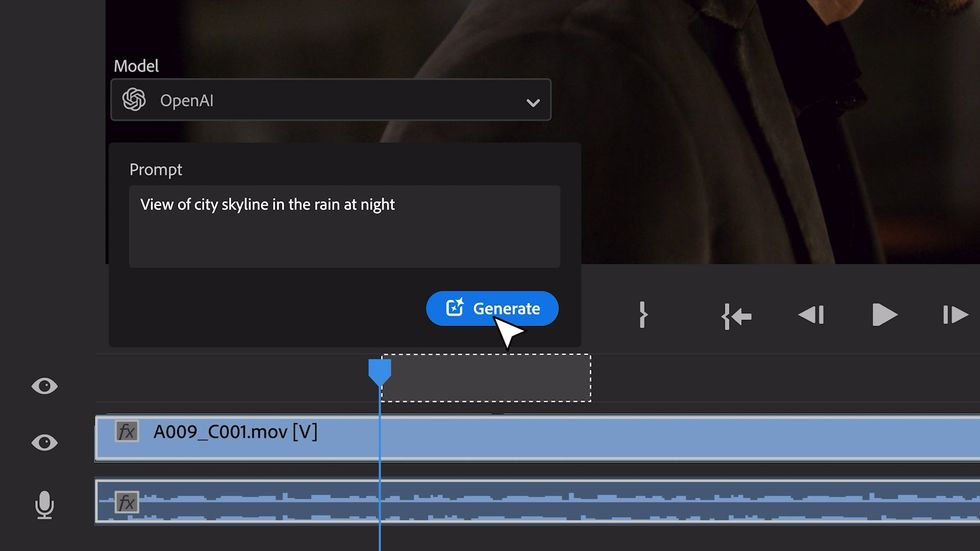

Isn’t that amazing? You can film an entire feature right now. You can! And you have access to better equipment than I started with in 2016! The hardware is better, the software is better, and you can work faster because of the lack of bottlenecks.

I really mean this: if you and a very small group of friends (or even just on your own) decide to make a feature film, you really can make it look as good or better than Hollywood.

If you suspected this was true before but were too afraid to try (understandably) then let me be your proof. It can be done.

So, if you’re a writer who dreams of becoming a feature filmmaker, you don’t have to wait anymore. It’ll still be a rough road, even with the technology now mature enough to make it possible, but you’ll be better for having done it. You’ll learn everything you need to as you go.

You’ll be a true feature filmmaker.

What are you waiting for?

Source: Kickstarter