4 Things to Keep in Mind When Making a Doc about War & Refugees

Translating national trauma and mass migration to film can be a daunting challenge. But as many filmmakers will attest, it’s also a necessary one.

During a panel at Berlinale Talents, the conference parallel to the Berlin Film Festival, directors of varying backgrounds shared their own unique strategies for wrestling with war.

“When there are no images of an inherited trauma, of a genocide of which we are survivors, what do we do?” asked panel moderator Rasha Salti, a programmer for the Toronto International Film Festival. “What images do we borrow, or construct, to refer to this experience – to the burden of this experience, to this experience being in our head?”

The panelists, who included Syrian, Afghan and German professional filmmakers alongside German student filmmakers, each had their own approach to this thorny question. Some highlights below:

Subvert expectations

German filmmaker Philip Scheffner was on YouTube one day when he found a very simple three-minute clip: a video of a small dinghy in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, captured from afar by a passenger onboard a cruise ship.

Fascinated by the clip, Scheffner set about researching its origins. He traveled to Algeria, where the refugees onboard the dinghy had come from, and interviewed family members he found there. And he found the videographer, a hospital security guard from Northern Ireland, interviewing him as well about what he saw.

But instead of using this filmed footage to supplement the original clip, Scheffner stretched the three-minute video to 90 minutes (approximating one frame per second) and layered audio from his interviews underneath. The “essay film” result, Havarie, screened in Berlinale’s Forum track.

In filming the refugee crisis, focusing only on images of the refugees themselves “neglects your own perspective,” Scheffner said during the panel. He said he was fascinated by the man who filmed the boat, whom he said was not the stereotypical image of an uncaring cruise ship passenger: “He filmed that whole thing with sympathy or empathy for people who are trying to get out.”

“It’s about us watching,” he said of his finished film. “It’s not about refugees.”

Bring historical context

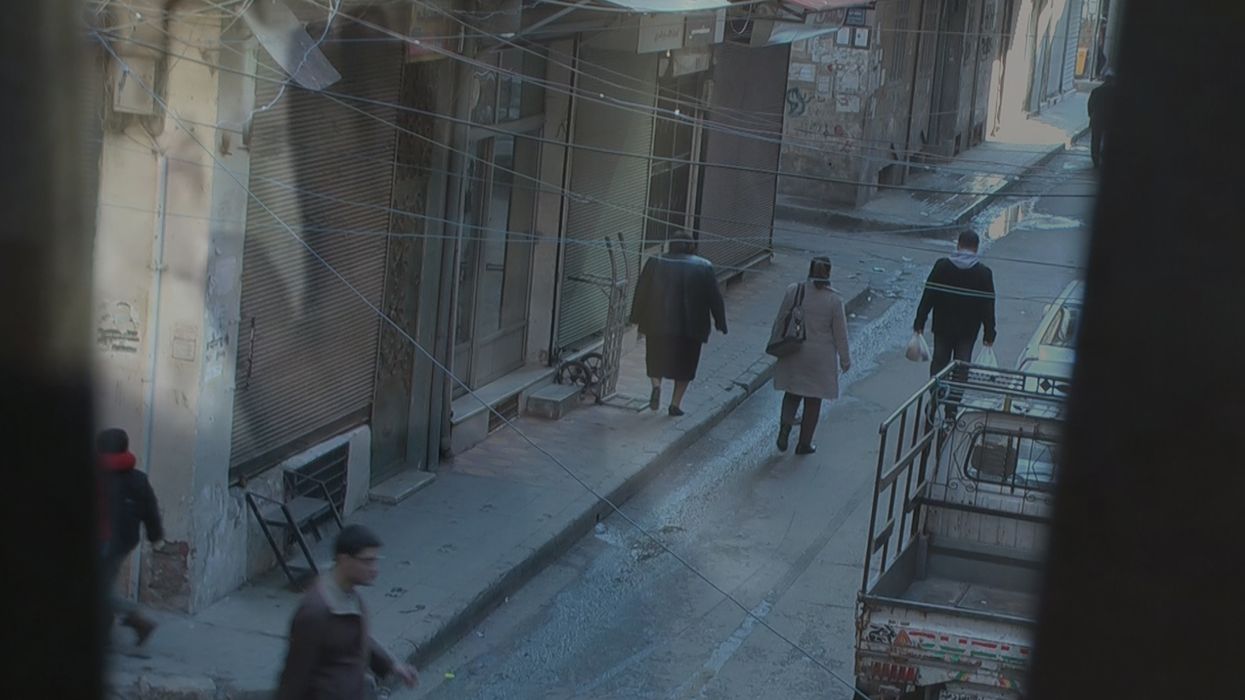

Another Berlinale entry, Houses Without Doors, is the work of Syrian-American filmmaker Avo Kaprealian. Filming the rising tensions of his home city of Aleppo from his apartment in 2012, Kaprealian makes the unusual decision for a documentarian to not introduce any of his central characters or give them proper narratives. Instead, he overlays the footage with audio from survivors of the Armenian genocide and footage from fictional films about the genocide, lending the present-day traumas of Syria’s heavily Armenian community a new context.

In so doing, Kaprealian said he didn’t make his film about present-day Syria, but instead about “a place where there is war.”

“I’m a filmmaker – I didn’t want to carry a gun,” he said at the panel. “Instead, I carried a camera.”

Limit the field of vision

In Slot in Memory, a 2013 short from Syrian filmmaker Khaled Abdulwahed, images of war are only visible through a tiny crack in an otherwise dark frame. Abdulwahed cuts between this crack and simple footage of children from Lebanon’s Sabra and Shatila refugee camps playing happily on a swing.

On the panel, Abdulwahed said he had initially set out to tell a more direct account of war and trauma, but because he was physically unable to reach warzones inside Syria, he felt he couldn’t do such a project justice. Instead, filming the kids, he discovered the swing they were playing on had a crack in it, which inspired him to make the visual connection with the obscured war footage.

Embrace young perspectives

After seeing that no established German filmmakers were adequately tackling the country’s huge influx of refugees, director Michael Klier supervised an omnibus film on the topic featuring several shorts from German film students. Research Refugees features several unique, outside-the-box perspectives on the crisis, but one short in particular, Duologue, struck the biggest chord with the panel.

In the short, a succession of young Arab men voice many of the fears real-life Germans have toward refugees like them. Directors Sophia Bösch and Sophie Linnenbaum interviewed Germans on the street, then played back their responses (many veering on the irrational or paranoid end of the spectrum) with their Arab cast mouthing the dialogue verbatim. The result recontextualizes a national fear of the unknown by having it come out of the mouths of the “unknowns” themselves.

To learn more about the films mentioned in this article, visit the Berlinale pages for Havarie, Houses Without Doors and Research Refugees: Duologue. And you can also check out Khaled Abdulwahed’s Vimeo page.

Be sure to check back for more coverage of Berlinale 2016.