David Mamet Reveals Why Movies Don't Need Dialogue and More No-Nonsense Screenwriting Lessons

Legendary playwright and screenwriter David Mamet discusses his no-nonsense approach to writing.

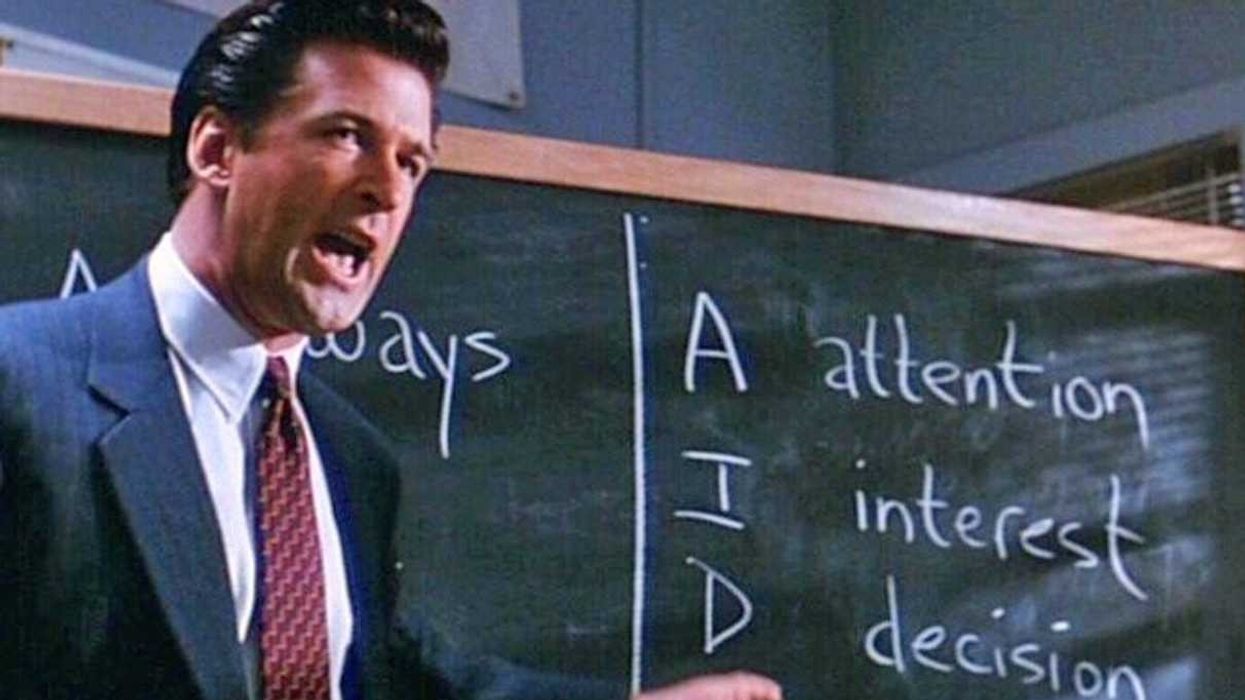

David Mamet doesn't mince words. He doesn't in his writing (Al Capone in The Untouchables: "You get further with a kind word and a gun than you do with a kind word"). He doesn't in his dramatic writing MasterClass ("Godard said every movie has to have a beginning, middle, and end, but not necessarily in that order. And that's why French movies are so effing boring"). And he certainly didn't in his recent interview with No Film School, during which he told us, "Hollywood is a cross between a spa and a cesspool."

Mamet has authored dozens of award-winning plays and screenplays, including The Verdict, The Untouchables, Hannibal, and Glengarry Glen Ross, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1984. He has also directed a number of his own screenplays, such as The Spanish Prisoner and House of Games, which won Best Film and Best Screenplay awards at the 1987 Venice Film Festival.

The founder of the Atlantic Theater Company is known for his distinctive style of dialogue, dubbed "Mamet Speak" and characterized by a cynical, caustic, street-smart edge. In a new online MasterClass (you can sign up here), Mamet outlines his pragmatic approach to dramatic writing. "Every scene should be able to answer three questions," he instructs. "Who wants what from whom? What happens if they don't get it? Why now?"

No Film School sat down with Mamet to discuss the content of his MasterClass, the do's and don'ts of a great screenplay, why Super Bowl commercials are great lessons in drama, and more. Stay tuned for a round-up of Mamet's best lessons and advice from his MasterClass on No Film School later this summer.

"You want to learn how to make a movie? Take your iPhone camera into the backyard and make a movie, for god's sake."

No Film School: What was the most important thing to communicate to film students about writing through this MasterClass?

David Mamet: Well, that's a good question. We all dramatize naturally. That's all gossip is—it's dramatizing. We take an event and rather than relating the police report of what actually happened, we unconsciously heighten those points which tend to illuminate our objective. An example is: Mary got off the bus and her skirt was so short, blah, blah, blah. And Joan said, "Bibbidi-bobbidi-boo." Well, maybe her skirt wasn't so short. Maybe the point was that Mary spends too much time shopping and she's too much interested in fashion.

Another example: "I spent four hours waiting to get on that plane." Well, probably you didn't spend four hours waiting to get on the plane; you just heightened the point of the story to a dramatic effect, which was that it was a wretched journey. We all do it naturally. When the audience suspends their disbelief when the lights go down, they are playing along with you. The audience is not there to say, "Wait a second! You probably didn't spend four hours." They get it. They're there to participate.

So the real task of learning how to write drama is learning how the audience thinks. And the only way to do that is in front of an audience.

NFS: What's the best way to find out if your screenplay works within the audience contract?

Mamet: Well, I would shoot the damn thing! And show it to people. Doing a reading around a table proves nothing. It's an absolute waste of time. In fact, having been involved in the movie business for many years, any time the director or actor says they want to do a reading around a table, you know what that means? It means they're never gonna make the movie. Nobody ever comes away from a reading around a table and says, "My god, this is great!" What the reading around the table proves is that it's not very interesting. Because it's not very interesting to read a screenplay.

If somebody wants to make the movie, reading a screenplay fires their imagination. They say, "Oh my god, I see just how this rocket's gonna work," or exactly how she's gonna look when she looks across at him. You don't get any of that when you do a reading around a table. So the only way you can find out if screenplay works is to shoot it and [play] it front of an audience.

NFS: In your MasterClass, you said that you should be able to write a screenplay effectively without dialogue. What are some tricks to mastering film's visual language so that you can communicate sans dialogue?

Mamet: A movie is a juxtaposition of images. We don't need dialogue in a movie. Never. How do we know? Because when we're on the airplane, we're looking across at the other guy in the next seat watching a movie and we get fascinated. We can't hear the dialogue. So what good is dialogue? Not very much good at all.

"If it can't be shot and it can't be spoken, don't write it in your screenplay."

If you look at the greatest film drama coming out of the United States, it's the Super Bowl commercials. I mean, some of them are only 10 seconds or 30 seconds long. But they tell a magnificent story and they tell it in a way that the ending is surprising and inevitable, and we sigh or we cry or we laugh. They're all told in pictures. The men and women who are making Super Bowl commercials are great dramatists because they understand the process. It's a juxtaposition of images. And if you can do it for 30 seconds, you can do it for an hour and a half. You just gotta keep doing it.

NFS: What are some ways you can write that visual technique on paper?

Mamet: Here's the best thing I can suggest: if it can't be shot and it can't be spoken, don't write it in your screenplay. This is an actual test that everybody can do right now.

If you read most screenplays, almost all of them are written by people with hardly any experience of actually making a movie. So they really don't understand how to write a screenplay. They say things like, "He came into the room, and you can see where he'd just been by the look in his crinkly eyes." Well, you can't shoot that. At the end of the day, all that you can do on the set is have the director say to the camera operator, "Put the camera over there and turn it on." Or have the director say to the actor or actress, "Say these words." That's it. You can't shoot "his crinkly eyes, which tell where he just came from."

"I want to see what film schools teach. I have this horrible suspicion they don't do much of anything."

The people who man the whorehouses of the Valley—the studio heads—are very forward, and I don't blame them. They're sitting around reading garbage all day. And they love that script that says, "Outside the window, New York and all its vicious splendor beckoned." But how do you shoot that?

I want to see what film schools teach. I have this horrible suspicion they don't do much of anything, except keep the kids off the street for four years. There are only three ways you can really learn how to make a movie: one is on the set, the other is in the cutting room, and the third is in the theater watching the audience. That's it.

Learning how to make a movie is very different from breaking into show business. I don't know how people break into show business. I mean, plenty of us do it, but we look back and say, "I don't know how I did it." But the that's a very different problem than learning how to make a movie. You want to learn how to make a movie? Take your iPhone camera into the backyard and make a movie, for god's sake.

NFS: In an interview, you once said, "The real violence in Hollywood isn't what's on the screen; it's what you have to do to raise the money." On our website, we talk a lot about fundraising and its pitfalls—how labyrinthine that process it can be.

Mamet: Oh, yeah. It's a very interesting environment out here. Hollywood is kind of a cross between a spa and a cesspool. It's a very difficult thing. I did so many things in addition to my day job as a playwright and novelist. I did so many movies, got so many of them produced. I had no idea how it happened.

NFS: In one of your lessons from the MasterClass, you suggest using a corkboard with sheets of paper or index cards to work out the progression of the plot. Is doing this analog important to the writing process?

Mamet: Well, it's important to do to me. I was in my rickety old age home before they invented the computer. I don't use the computer. I write things down. Here's the thing: I tried several times, but it's just too slow for me. If I've got the whole movie spread out on a corkboard, I've got 100 sheets of paper and I can take them and replug them here, replug them there, replug them there. I don't have to go through the process of pushing a lot of buttons. But that's just me. There's nothing wrong with the computer; I just hate it.

"Hollywood is a cross between a spa and a cesspool."

NFS: In the class, you place a large emphasis on progression, and even suggest taking out a scene if it doesn't directly advance the plot.

Mamet: Well, frankly, I find the process fascinating. Writing a drama is an adventure, and as the old phrase goes, "The difference between an adventure and a vacation is that when you're on an adventure, you wish you were home." Writing is a lot of times unpleasant, but it's an adventure. If you're having fun all the time, you might be doing something wrong. But what is worth doing that's easy all the time? Writing is very gratifying. But sometimes it's a pain in the ass.

NFS: What are lessons you've learned the hard way from your career as a writer?

Mamet: First thing: There's no such thing as best efforts. If someone says they're gonna use their best efforts to do something, that means, "Stand by, I'm gonna screw you later on, and you're going to agree to it now."

Mamet: Another one of the great lessons I learned early on—I can't remember who I learned this from—was in your first meeting with someone who it looks like you might be doing business with, bring them a gift. It absolutely does not have to be expensive, but the gift should indicate that you spent some time figuring out what would [show] them that you value the relationship. Find out what they're interested in. Spend a few bucks on them. Have it wrapped really simply and give it to them.

Then, see how they react. Because that's how they're going to treat you in the course of the relationship.

NFS: One of the main tenets of this class—and of your philosophy of writing—seems to be that characters in a drama always want something. Sometimes, writers struggle to distil what it is their character wants specifically in every single scene, especially if it seems to be a straightforward scene without much subtext. Why should we always define what the main character wants?

Mamet: Well, every scene is about what the main character wants. I mean, think about it like a war. World War II breaks out. We have to fight Japan and we have to fight the Nazis. We aren't interested in what Botswana wants. Botswana might want something very legitimate, but that's not our interest. Our interest with the main character is to defeat these two fascist powers. So every [drama] is about what the main character wants. That's it.

These are very simple rules I'm talking about in the MasterClass. They kind of take forever to understand, and then a subsequent helping of forever to begin to master. And one never masters them completely, but it's fun trying.

Except when it's a pain in the tush.

Featured image of Alec Baldwin in 'Glengarry Glenn Ross,' written by David Mamet