Filming Abroad for VICELAND: 'Befriend Local Sex Workers and Cabbies'

Filmmaker Aaron Ohlmann has risked life and limb on more than a few occasions to get the right shot.

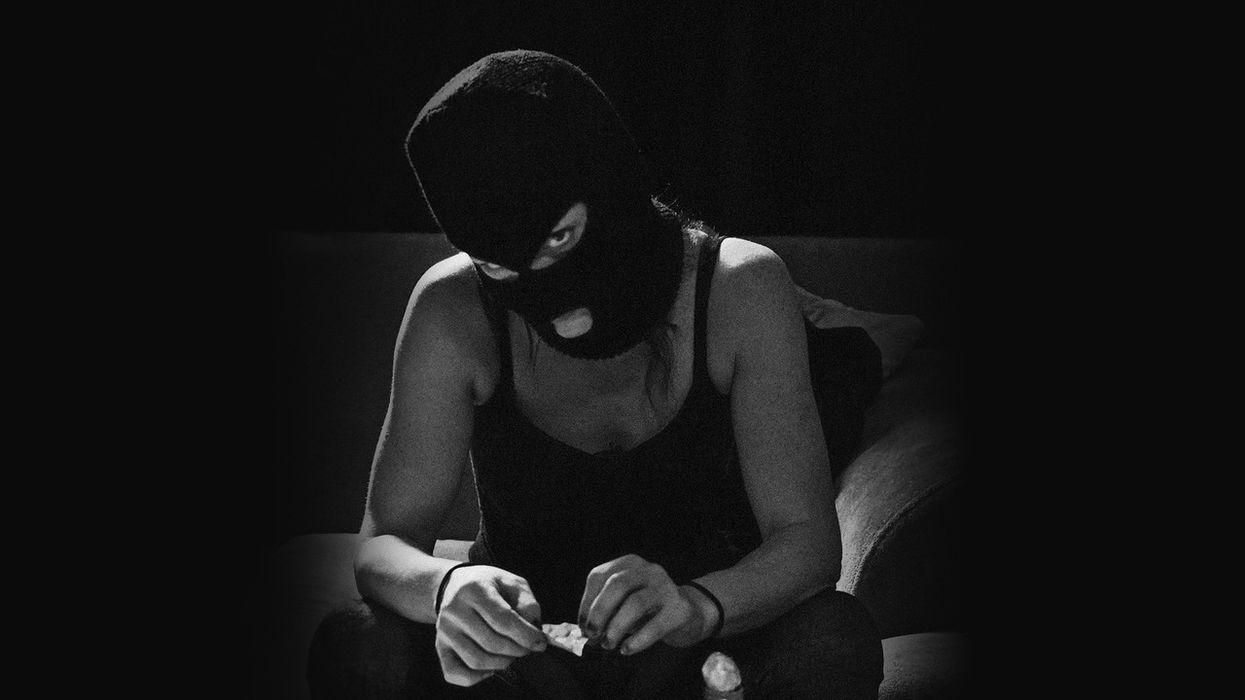

With experience filming in over 54 countries, Aaron Ohlmann has covered underground hip hop artists in Cuba, refugees fleeing the battle with ISIS in Iraq, and survivors of sexual violence in Mogadishu. VICELAND's series Black Market, now in its second season, features two of Ohlmann's new pieces: one that follows West African poachers and one inside the Japanese Yakuza.

"My priority is not to die. It would be incredibly stupid to become a martyr for any cause, particularly filmmaking."

No Film School spoke to Ohlmann about how he approaches his work, philosophically and physically.

No Film School: What is your first step in finding and gaining access to your subjects?

Ohlmann: I connect with a local fixer—preferably, someone I have worked with before, or someone who comes recommended from someone I trust. The last time I was in Iraq, some contingencies fell through last minute, and I had to get a fixer from a private Facebook group—not optimal, as it’s the equivalent of a Tinder date walking you through a war zone. It clutters the head with unnecessary worries, like getting sold to ISIS.

"Experience has taught me to be much more afraid of bad drivers in Corollas than of bad men with Kalashnikovs."

NFS: How do you find a good contact on the ground when you’re shooting in remote or foreign locations?

Ohlmann: Cultivate a network and try to get some recommendations in advance. For all its stupidity, social media is brilliant in this category. Friends of friends of friends can get you just about anywhere on the planet, particularly if you have a few slightly dubious friends. If all else fails, befriend local sex workers and cab drivers. They know better than most how the city moves.

NFS: How far in advance do you usually set up your shoots? What impact, if any, does this have on the behavior or approach to your subjects?

Ohlmann: I plan just enough to be able to improvise. For me, that means setting myself up to be light and mobile, informed about the environment I’m shooting, but not so informed that I think I know what I’m doing. I never want to become so attached to an idea that I can’t abandon it completely once I’m on the ground.

As for subjects, I try to make them informed partners in the process, but part of that includes building in a certain amount of flexibility and uncertainty. During and after the shoot I like to share photos so they have their own documentation. As an experiment, try to fall in love with them or the way they see the world. See how it makes you feel, and report that back.

NFS: When you find yourself in a dangerous situation, how do you define your priorities?

Ohlmann: Generally speaking, my priority is not to die. It would be incredibly stupid to become a martyr for any cause, particularly filmmaking. That said, I think in many of the countries I’ve worked in, people tend to overestimate the risks just because the idea of certain acts of violence overrules the brain’s understanding of probability. Experience has taught me to be much more afraid of bad drivers in Corollas than of bad men with Kalashnikovs. Of course, the rules are different everywhere, so I look to trusted local partners to help keep things in check; if they’re not nervous, I’m not nervous. If they say it’s time to go, our first priority is getting out as quickly as possible.

NFS: Does your responsibility to your subjects change when they are involved in illegal activity?

Ohlmann: That was something I thought about a lot when I was working on Black Market because that dynamic was the entire backbone of the show. Everything we shot ranged from a little illegal to wildly, recklessly, "Oh shit, what are we doing?!" kind of illegal. And to add to the complexity, oftentimes our characters were already on the radar of local law enforcement, who are themselves partnering—or at least implicated in—the same illegal activity.

"[Fractal mediation is] forcing us to take ownership over our point of view and stop pretending to have access to objectivity."

But to answer the question: If people ask to remain anonymous, then that needs to be taken very very seriously. I spent a year working with classified material at the UN’s tribunal for the Rwandan Genocide and I saw the horror that can happen when informants and witnesses are not protected. I’d torch my laptop and kill a story before betraying that trust. Beyond that, if people are informed about what we’re doing and they consent to being filmed, my responsibility to them is the same as to anyone I shoot.

Ohlmann: Adderall, Ativan, and a Sony a7S ii with a Sennheiser MKE600. And we’ve got the new pint-sized Mavic Pro drone on pre-order, which I’m pretty excited about after getting larger drones confiscated at customs.

NFS: As we live in a more mediated world, what role does documentary film serve in communicating “messages” or bringing attention to “causes”? Why is documentary film an effective medium?

Ohlmann: It’s fascinating to see a sort of wild exponential fractal mediation that is, in some ways at least, making documentary filmmakers more honest. It’s forcing us to take ownership over our point of view and stop pretending to have access to objectivity. To lift a line from Ben Ehrenreich’s brilliantly unapologetic introduction to his book The Way to the Spring, “[Objectivity] isn’t a virtue or even a possibility… We are all of us subjects, stuck fast to bodies, places, histories, points of view.”

"Everyone involved, on both sides of the camera, loses a little integrity along the way."

Filmmakers who embrace that idea wield incredible power because they can form intimate connections with an audience that can be difficult in other mediums. Werner Herzog and Errol Morris have been doing this a long time. Joshua Oppenheimer and Mads Brügger both toy with this in different ways. VICE’s brand of first-person journalism exploits this incredibly well, and online, short-form filmmakers like Max Joseph or Nirvan Mullick have raised millions for social causes by making it clear where they stand. They show us part of themselves, we connect, and in exchange we’re willing to be led to places we never would have cared to travel in the hands of a disembodied Ken Burns.

NFS: How do you, as a documentary filmmaker, tow the dangerous line between communication and didacticism?

Ohlmann: This is a personal mission of mine, actually. I’ve been doing a lot of work for the United Nations lately, and have seen their long history of cranking out thousands of videos a year that don’t get seen because they’re didactic propaganda pieces that try to pass themselves off as objective documentaries. People are too smart for that. It’s boring. What we’re trying to do for the UN is make films that take ownership over their own viewpoint, that aren't afraid to tell the audience where they stand and what they see and do it in an entertaining way. When we’re successful, it makes for much more watchable and sharable films.

NFS: How do you commit a subject to film without exploiting the integrity of that subject?

Ohlmann: On some level, you can’t really. Of course, you try to make honest work, tell illuminating stories, and do right by your subjects. That’s why we do what we do. But at some point in every shoot, I think about Herzog’s line about how “filmmaking turns everyone into clowns.” It’s true for a lot of mediums, but especially for documentary. You’re working to portray infinitely complex living human beings, and no matter how you shoot them, they are always going to be caricatures of themselves painted in a 16x9 rectangle flickering at 20-some frames a second, sometimes with act breaks for commercials. Everyone involved, on both sides of the camera, loses a little integrity along the way. All you can do is embrace the medium’s many indignities and try to make work that finds its niche and participates in the culture.

'Black Market: Dispatches' is now available on Amazon video.

'Sunfish (& Other Stories on Green Lake)'CREDIT: JWH Films

'Sunfish (& Other Stories on Green Lake)'CREDIT: JWH Films