4 Paths to Writing for Non-Fiction

Until recently, documentaries weren't known for having screenplays, or so we thought.

In earlier times, a documentary was considered a journalistic pursuit, as filmmakers were seen to be striving for objectivity. However, as the genre continued to come into its own, becoming identified with having a cinematic power (and reaching the "status" of its fiction counterpart), the gap is now closing between fiction and nonfiction film.

Screenplays aren't just for fiction films anymore. In a panel at DOC NYC titled Writing for Non-Fiction, four award-winning documentary filmmakers came together to discuss their writing process and the discoveries they made while crafting their screenplays. Here are some takeaways.

1. “We resisted having cards in the beginning but [ultimately] decided there is information we must have.”

— Sarah Burns, co-director, writer, and producer of The Central Park Five

Sarah Burns came to the story while reading a book on five young men of color who were wrongly convicted of a raping a woman in 1989. After the men served a number of years in prison, the true rapist came forward and confessed.

For Burns, one of the core ideas of her film was to create a “platform for the convicted to express themselves in their own words.” Burns and her directing team (Ken Burns and David McMahon) wanted the audience to know, right from the beginning of her film, that The Central Park Five were not guilty. “We were never going to not tell you that,” Burns said. The film was not a “who-done it” story, but rather an expose of the injustice that occurred when these young men's lives were upended unfairly.

Knowing this from the beginning allowed the directors to write the opening of the film creatively, setting up the tone and making sure the audience knew what they needed to in order to avoid later confusion. “We resisted having cards in the beginning, but [ultimately] decided there is information we must have,” Burns admitted. Because one of the five men did not wish to appear on screen, it was important to convey that request from the start, explicitly highlighting that the coverage of him was going to be different. We also hear the real perpetrator's confession while seeing footage of Central Park at the crime scene.

Rather than rigidly stick to the original idea to not use information cards, the directors crafted the opening to serve the overall objectives and story of the film This flexibility set up the film in a way that ultimately made sense.

2. “I wanted to make a more experimental, essayistic film but it wasn’t working."

— Cecilia Aldarondo, director of Memories of a Penitent Heart

There were initially lots of research and planning for the story Cecilia Aldarondo wanted to tell, but then, the world of the documentary “knocked me off my feet," Aldarondo recalled, "and the world forces you into shifting what your sense of the story is.”

The film was guided by investigation, discovery, and the excavation of a family history. Opposed to sticking to the story she thought she was telling, Aldarondo stayed open to the twists and turns that appeared while she was producing the film, following its lead. “If we can't respect that nonfiction filmmaking depends on after-the-factness then we end up making formulaic films,” she said.

Like Burns, Aldarondo initially had some pretty clear ideas of the film's style, but there was a moment when she realized that it wouldn’t serve the film as a whole. “I wanted to make a more experimental, essayistic film, but it wasn’t working,” she said. For Aldarondo, having a flexible editor (Hannah Buck) allowed her to play, experiment and fail. “We did a lot of weird experiments with archival … the editing room was a laboratory of trial and error. If I had an editor who was more strict about the process, it wouldn’t have worked.”

It was this collaboration that Aldarondo credits to her film’s success. As parting advice, Aldarondo offers, “I think the reason why docs fail is because the director didn’t listen to their editor. ... I say, listen to your editor.”

3. "The characters in my film did not get to testify in court or be taken seriously, and so I didn’t interrupt my subjects when we shot their interviews. [I wanted them] to have a chance to testify."

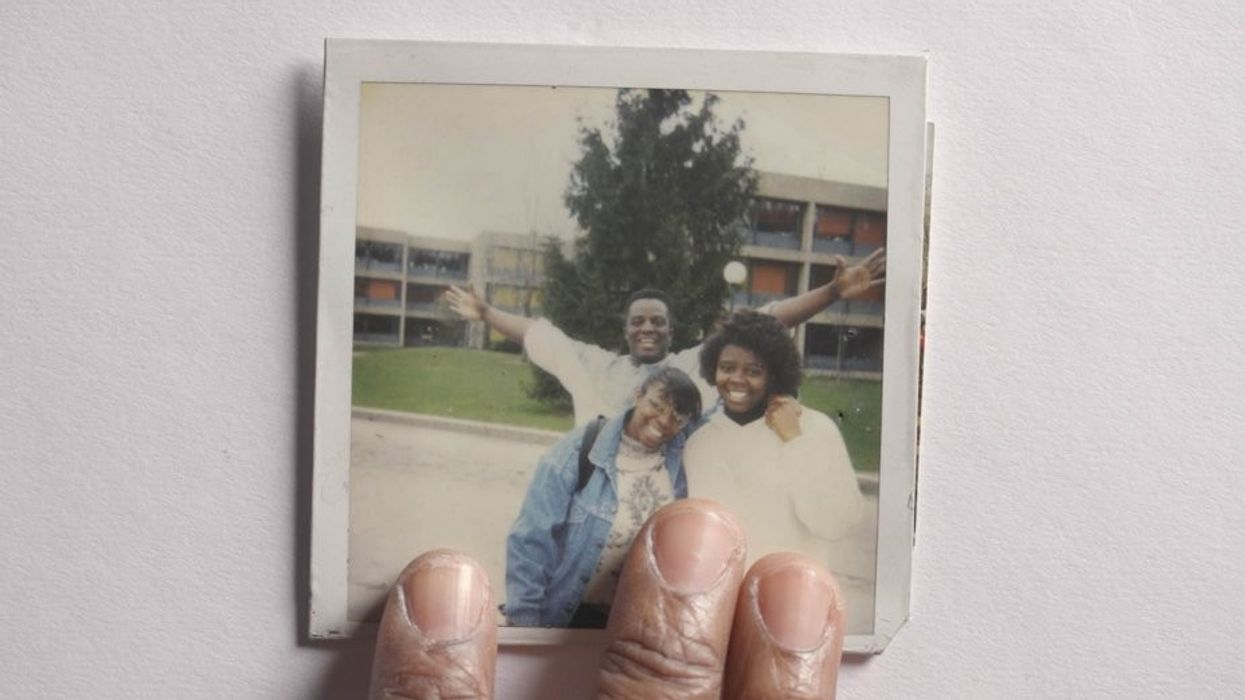

— Yance Ford, Director of Strong Island

Despite the popularity of the nonfiction genre and the themes of Strong Island, Ford clarifies that it’s not a True Crime story. "The characters in my film did not get to testify in court or be taken seriously," Ford recalled, "and so I didn’t interrupt my subjects when we shot their interviews. [I wanted them] to have a chance to testify….[the] things no one asked or cared about 25 years ago….the question wasn’t what but why.'"

Ford was able to allow his characters to tell the story from their own perspective, so that they could take control of the narrative: a narrative which had been twisted in the favor of a young, white man in the hands of an all-white jury. There is power and dignity in telling one’s own story, and Strong Island was the mechanism to restore those attributes to a family whose community and society had taken them away.

In the film, Ford says about his brother who was murdered, “I am unwilling to accept that someone else gets to say who Williams was. And if you’re uncomfortable with me asking these questions, you should probably get up and go.” The one thing that Ford said was most helpful in remaining true to the story's strong emotions, thoughts, and ideas was to keep a production journal. Ford says that writing a treatment is different from story writing, advising filmmakers to “have some place else you’re doing your brain dumps and [writing down] stuff that comes to you in the middle of the night.”

4. “The biggest challenge was recognizing that in order to tell a story that will make people lean forward and listen, we'll have to get very honest.”

— David Riker, writer and editor of Dirty Wars

In Dirty Wars, David Riker was most concerned with getting to the truth of the subject matter. The “biggest challenge was recognizing that in order to tell a story that will make people lean forward and listen, we'll have to get very honest.” Because of the highly controversial subject matter, his team had to be very strategic in crafting the story so that people would not only pay attention, but believe what they were being told. Because of the highly controversial subject matter, his team had to strategically craft the story so that people would not only pay attention but believe what they were being told.

In Dirty Wars, this was achieved through the following of journalist Jeremy Scahill on the front lines, seeing the story through his lens. Riker was aware that when a journalist reports on a story, he or she is (most often) to be left out of it. The journalist’s thoughts or feelings are to be kept to themselves. Dirty Wars relies on the journalist’s personal report and breaks through that veneer of objectivity. “[The journalist’s story] is not supposed to be relevant, but to me it’s vital. We asked Jeremy to tell his part of the story,” said Riker.

One of Riker's biggest questions regarding how to break through to his audience was “how to speak to an American audience.” Riker wishes he’d been taught about story sooner. “I think it’s changing now. Documentary filmmakers are studying storytelling. For a long time you wanted to go out into the unknown without thinking of the outcome.”

'Sunfish (& Other Stories on Green Lake)'CREDIT: JWH Films

'Sunfish (& Other Stories on Green Lake)'CREDIT: JWH Films