'Strong Island': Yance Ford Breaks the Silence on His Brother's Death in Oscar-Nominated Doc

Yance Ford interviews his family to address the injustice surrounding his brother's killing. And makes history as the first transgender Oscar nominee.

This past week, Yance Ford made history when his directorial debut Strong Island earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary Feature. He is the first transgender director to ever receive an Oscar nomination, a watershed event that hinged upon Ford’s willingness to reclaim his family’s narrative and the courage it took to own and to tell the story of a loved one that had, for so long, been eclipsed by the social and psychological implications of black identity in the United States.

In April 1992, just 22 days before four LAPD officers were acquitted of criminal charges for their beating of Rodney King, Ford’s older brother, William Ford Jr., was shot and murdered by a 19-year-old white man who claimed he fired in self defense. William became the prime suspect in his own murder and the white man walked free. Justice went unserved and the Ford family slipped into a state of silence and retreated into a stagnant state of grief.

Yance Ford’s Strong Island is an expression of the indelible mark William’s death left on their family and its historical resonances with the structure of blackness in America, in their home and in the world across time. Stepping outside of the protective shield that secrets had long provided, a containment of the family’s rage at the indignities of their son’s murder, Yance Ford opens the door to his past and explores the causes and effects behind the trauma that shook their family. Strong Island finds another kind of justice by contending with fear and seeking out truth.

No Film School sat down with Yance Ford to discuss his dual roll as director and character, the aesthetics of absence, and the power one derives from breaking a history of silence.

No Film School: Strong Island derives much of its strength from the vulnerability shown by its characters, one of whom is yourself. Was it always your intention appear on camera as an interviewee in your own film?

Yance Ford: When I first started to make Strong Island, I had a list of ten rules and rule number one was that “Yance will never, ever appear on screen; and if Yance appears on camera, it will only be to play the role of William Ford Jr. in one of the final scenes.” So, yes, I definitely wasn’t planning on being in the film originally, but I did know I needed to be interviewed at some point. I think for me, having decided to make a film that was born out of personal experience, I knew I needed to have a voice in the film. I just thought my voice could be non-sync, through voiceover or some other means.

But as the project evolved, it became impossible to justify my absence from the film. I had asked all the interview participants to take a tremendous risk in talking to me about William’s murder and to break a silence—a heavy silence—after many, many years of not talking about it at all. Not only did it feel like I was taking the easy way out, but I felt like my voice was absent in a really… in a weird and unnatural way, by avoiding the camera. It required something else from me that I wasn’t willing or able to give up until approached the film for a second time. I had to step outside of my comfort zone because my brother’s death happened to the five of us, to our whole family. Strong Island shows what that long tale of grief and silence looks like and I needed to reach a place where I could offer the same amount of access to my experience that others involved were willing to do.

But the distance between me and the camera had to be adjusted. I think the cameraman might have been playing around with the focus, but we both knew the shot had to be tighter for me. I mean, you can put my mother on a billboard of a highway and everyone would stop their cars and listen to whatever she has to say. I don’t have that. I have the stoicism of my father combined with the eloquence of my mother. You have to get super close to me to actually see me fully, to really feel what I’m saying. I think it’s partly just because, you know, I’ve got that New York face on and partly because people often misinterpret my facial expressions. You can look at me and think, “Oh, Yance must be feeling a little angry right now,” when in reality I’m thinking, “Is my cat missing me?” I wanted to collapse that distance so that you could see the emotion of my character and so that my character could be read in the same way that other characters were read in the film. That’s how we wound up two inches from my face and with a very narrow focus field. If I ever got tired and leaned forward a bit, I’d come out of focus and have to sit back up. This is all to say that it was essentially an exercise in sitting up straight for many, many hours at a time.

NFS: As a director, you’re responsible for creating a safe, comfortable environment for your characters so that they can share their experience as openly and as honestly as they can. But in Strong Island you’re taking up the dual role of director and character. Did the interview process change when you were the one in front of the camera, answering the questions rather than asking them?

Ford: If I was going to say things I had never said before, I had to be as alone as I possibly could. I didn’t want to see anybody, I didn’t really want to hear anybody. There was literally a wall of sound blankets that I had constructed between myself and the crew. Really. A line of blankets. People on the other side of the blankets could see me from the monitor, but I couldn’t see anybody. All I could see were two lenses and two marks. I didn’t know what I was going to be asked in advance, no one knew. It took that kind of distancing myself from the crew and from the person that was interviewing me in order to be vulnerable and to allow myself to process the questions in real time. And that’s how they shot me over the course of six years. After establishing what the frame would look like and what the character would look like, I ceded the reigns of control over to my colleagues and stepped back into the role of William’s sibling who also had a story to tell. It was really hard.

"I had reached the point where being silent was harder than it was to take the risk of sharing my story and making this film."

NFS: That was at the forefront of my mind when you appeared on screen. I kept thinking about what an arduous, unsettling process it must have been to revisit these traumatic events, and especially, to actually express out loud for the first time how William’s death affected you. Did the nature of your grief shift in any way through that process?

Ford: Grief and trauma and the way it’s passed down over time and the way that it sort of changes and morphs over time is really one of the themes of the film. We see the way that my brother’s death has an impact on every character. My father has a massive stroke the year after my brother was killed and you know I tie that directly to the silence that descended on our family after all avenues were exhausted and my parents were left with a hot mess of injustice and no other avenues to pursue. I don’t think the film necessarily brought me to a new place in terms of where William’s death fits into my life because he had been dead for 15 years when I started making the film. I was quite accustomed to what that grief was like on a day-to-day basis and how it changed.

What’s different for me is talking about it. Despite having been in a very high profile position for so many years in the documentary community, no one in this world even knew I had a brother. So by sharing this part of my life, there’s a sort of coming out. For families who have experienced this kind of traumatic death, there is a great deal of silence and there’s a great deal of shame and there’s a great deal of protection. This, I feel, is particularly true for those families whose loved ones were murdered, and then watched those killings be justified with scant evidence of justifiable anything. Silence is about protecting each other, but it's also about protecting yourself. I mean you don't necessarily spring that conversation on someone casually over lunch, right? But you can have that conversation over the course of 107 minutes in Strong Island. I think it's a deeper and richer film because I finally got tired of being silent about it. I had reached the point where being silent was harder than it was to take the risk of sharing my story and making this film. And that reveal, the decision to stop being silent, is where I begin Strong Island.

NFS: What was it like for your mother and your sister to disclose their experience to you, both as director and as a member of the family? In doing so, did you see a change in the way you all related to the event?

Ford: You know, we all talked to each other for the first time about William’s murder as a result of Strong Island. And breaking down that barrier and being able to talk to one another about his death was a great relief to all of us. And the fact that the film was going to be made, even though, SPOILER, my mother never lived to see it, at least, every time she sat down for an interview, every time that we ended up at her house to shoot for 18 hours over the course of those six years, she knew that William’s story was going to be told and it lifted the burden that she had been living with for many, many years knowing that I had begun this endeavor. I don't think that she would have imagined the turn of events and how her grief over my brother’s death would ultimately express itself after my father died, which was this second traumatic event of great significance that the family had endured, but she was happy that the world would finally come to know what happened to William. Because he was like a soap bubble. He was there one minute and then *pop* he was gone.

"We asked ourselves, 'How do you shoot the remnants of things that used to be in a place? What does it mean to shoot silence?'"

The casual fragility of black life is something I don’t think many people can fully appreciate. If you don’t experience it or if you’re not open to seeing it in the experience of others, you have absolutely no idea what it’s like to have someone simply disappear. The shooting style was influenced by a desire to see things that aren’t there anymore. When I spoke with Alan Jacobsen, our cinematographer, about how I wanted the film to look, we talked about many of the emotional themes of Strong Island: absence and longing and loss. Also negative space. We asked ourselves, "How do you shoot the remnants of things that used to be in a place? What does it mean to shoot silence?" The aesthetic, in many ways, is informed by all of these questions.

NFS: I was really taken with the way you shot interiors. In your hands, the house became another character, in that it registered emotionally, hauntingly. What informed your aesthetic choices? The way you occluded faces, played with focus, your framing.

Ford: A lot of the cinematography is meant to obscure. It’s meant to convey to the audience that you’re seeing what I want you to see, and what I want you to see reflects the way my family lived in the aftermath of William’s murder. There’s that shot of my mother while she’s doing the dishes that’s taken from outside of the house. We were outside on the porch shooting through the kitchen window without her knowledge—she didn’t know we were out there peering in. So that moment is a completely unguarded moment on her part. And seeing this moment, the way you can look at her face and just know she’s thinking about William, demands a kind of voyeurism on our part, right? You can only get that if you’re us, the crew, sneaking around in the backyard and pointing a camera through the window. Then, at other times, you don’t get to see what’s outside the frame. That occlusion is deliberate as well because it evokes the privacy and the guardedness that comes to be this protective shield when the system of justice that you actually bought into has turned on you. It’s failed you. So it’s a very controlled frame. It’s not a frenetic frame, it’s not a handheld frame. We always shot on sticks.

Mostly, Strong Island’s cinematography and our formalistic decisions therein are a reflection of how the entire film came to be. We spent a lot of time looking. I look at stuff a lot. And I also look at the house. You know, after my father died, I was partly in charge of making sure that the shit that was broken got fixed. That’s why there are all of these low-angle shots in the film because the camera is not a surrogate for the audience. The camera is always my eye. So that’s what informs the different angles and the different things around the house that I chose to include. That’s why you, as the audience, are at a certain distance. It’s all meant to replicate the way that I looked at the community that I grew up in and the way that I looked at the interior of my house and the way that we look at each other, my mother, my sister and me, and ultimately, my brother’s best friend and all the other characters of my film.

NFS: I’m struck by the clarity with which you discuss your own process or grieving William’s death. It sounds like the challenge for you was breaking the silence, rather than contending with the past.

Ford: Yeah, honestly I think it comes from having studied art. And it comes from having thought I was going to be a neurosurgeon and then flunking organic chemistry, flunking physics, flunking math and eventually realizing that I wasn’t actually going to make it to medical school. And ultimately in finding that there was an expressiveness in art. The study and practice of art was suited to my voice and helped me find it when I was young, around 18 and 19. William was murdered when I was 19, when I was a sophomore in college, a week before my 20th birthday. I immediately began incorporating his death into my work as an aspiring artist. That photographic eye, and my affinity with performance art and its ability to manifest things in certain situations, helped me change my relationship to the event and my grief. I’ve had my art critiqued many times, on a weekly basis in college, during which you’re constantly drilled about intention and execution and form and content. In that way, I was used to the process of starting over again. When I took a step back from the film after my mother died, I was able to ask myself those sort of questions. It became clear to me that Strong Island required something else of me that I wasn’t willing or able to give. I left the country to edit the film from scratch and it was there, in Denmark, that I created a new structure and where this version of the film began.

I also think I benefited from being in a country where the American criminal justice system makes no sense. In Denmark, they don’t have a grand jury, so explaining how my brother’s murderer walked away unpunished didn’t translate easily. I had to sort of convince people that our crazy system could work this way while I was there: “No, it actually happens like this and it happens like this all the time.” It helped me understand the easiest ways to explain the insanity of the system to people, but it also helped me talk about the process and intent of making this film. I think also, there is something to be said about the alienation I felt while I was away in this foreign country. When I got to Copenhagen, I was the only brown skinned person around. So being a black person in Denmark during Brexit, during the explosion of the migrant crisis and the subsequent pushback against migrants, helped clarify what my family and I had been through.

I wound up in Denmark because that's where my editor was, but I found that this dislocation gave me more courage than I already had to talk about the film and to sort of state a claim. You know? It helped to peel back the layer of defensiveness that had prevented me from talking about race as I’ve lived it and as I live it now. I know that some people that watch this film will be fixed in their views about race and the criminal justice system, and I know that some people will perhaps approach the film with a more open mind. It's my job to both be present in the film and during these interviews. I try to be as present as I can in conversations like this because that’s my duty in the film and that’s my duty now, rather than retreat behind it. I could just as well say, “No, thank you. I’m not going to do any interviews. I’ve already done enough.”

"That’s why we start the film with my mother sharing my parents' love story. We want to invite people into the family because my family didn't start with my brother's murder."

NFS: It shows tremendous courage and resiliency that you don’t shy away from these opportunities given the amount of time you’ve dedicated to telling and re-telling your family’s story. I can only imagine the range of questions you must get during Q&As and how uncomfortable some of them might be. That’s not an easy thing to be present for.

Ford: It's not. It’s not. It’s been an incredible experience to have been on the road with this movie, since January [2017]! Everywhere I go, the audience response is amazing. The Q&As are intense as are my exchanges with people who want to talk to me afterward. Sometimes, there are only a couple, and other times there are like 30 or 40 people who stand around for hours to say thank you or who want to share their own story of a loved one that they lost to homicide. It’s one of the beautiful things about Strong Island. In many ways, it's giving people permission to talk about the traumas that they've suffered. Often for the first time. That has been a gift.

NFS: That's what film has always given me: an opportunity to identify with or relate to something that I had never felt permission to admit or it reveals something that I've been afraid to acknowledge as a truth. In the same vein, film provides a lens through which I can see a new kind of reality, often from vantage points I wouldn’t be able to access otherwise. In this way, film becomes a collaboration between the director’s perspective on the world and my own process of relating it back to my own experience.

Ford: That’s why we start the film with my mother sharing my parents' love story. We want to invite people into the family because my family didn't start with my brother's murder. My family actually started with my parents falling in love all the way back in junior high school. That invitation and warmth in the beginning is part of why the film has been a success. And, you know, partly because my mother is irresistible and partly because she's a lot of people's mothers. That's my mom. My mother never met a stranger. It's a figure of speech that she used to use. You know her funeral was just a constellation of people, some of whom I've never met before. That’s a testament to her character.

Strong Island is streaming now on Netflix.

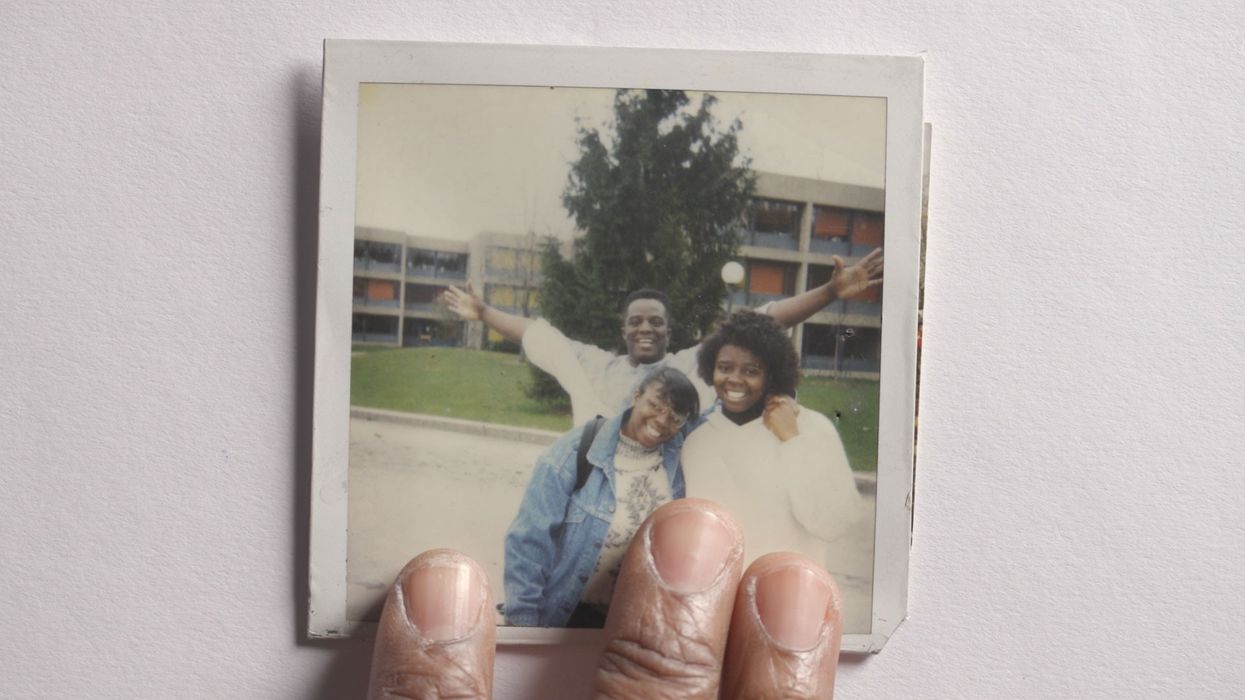

Featured image: William Ford Jr., Lauren Ford and Yance Ford in a photograph featured in 'Strong Island'. Courtesy of Netflix.

'Sunfish (& Other Stories on Green Lake)'CREDIT: JWH Films

'Sunfish (& Other Stories on Green Lake)'CREDIT: JWH Films