'A Crazy Journey': How True Crime and a Pizza Delivery Man Inspired 'Evil Genius'

Netflix's multi-part documentary from Barbara Schroeder and Trey Borzillieri features a story so crazy it could only, unfortunately, be true.

What kind of novelist would you have to be to come up with this particular opening: A man, explaining that he is being held hostage, walks into a bank with a bomb strapped to his neck and says that if he doesn't receive $25,000, the bomb will go off.

The man has a collection of papers with some very intricate instructions written on them. Some for the bank and some for the hostage, a series of steps must be completed in order to prevent the explosion. The bank, as it turns out, doesn't have enough money; the man leaves, and a few hours later, during a tense standoff with local police, the bomb explodes.

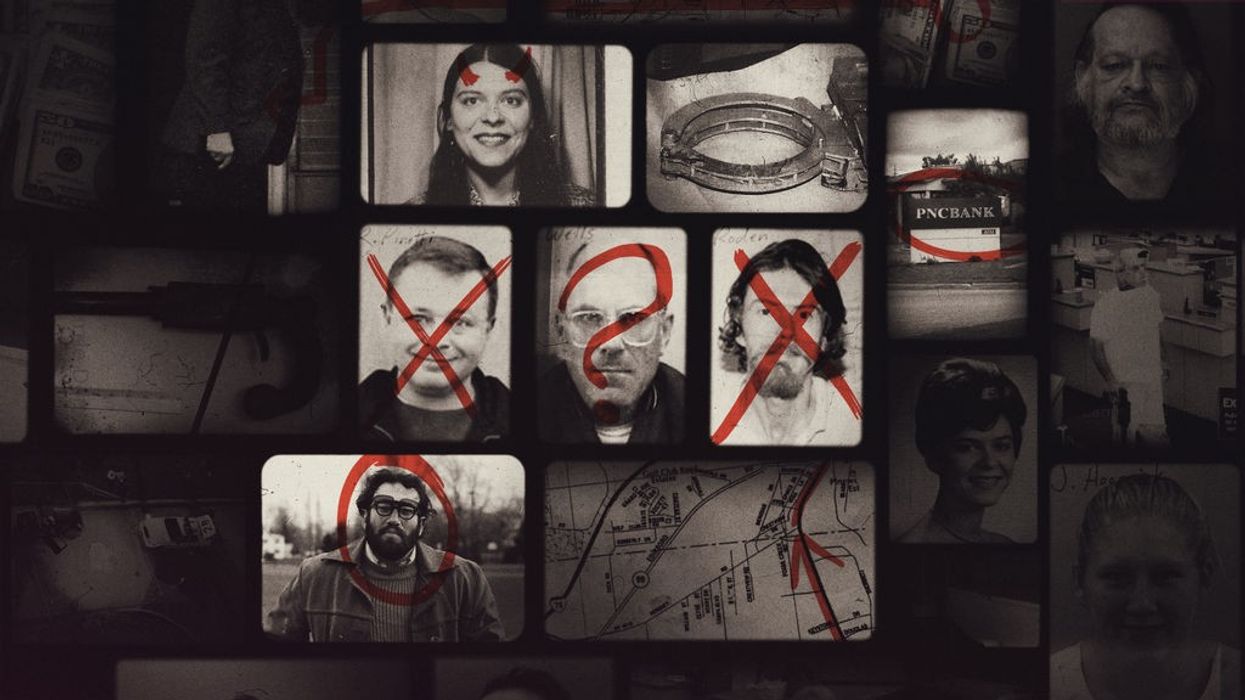

Surprising as it may seem, this event did actually occur, in Erie, Pennsylvania in 2003; each of the figures both directly and indirectly involved in the event, from Brian Wells—known to many as the "pizza bomber" because he had worked for 30 years prior as a pizza deliver—to Kenneth Barnes and William Rothstein—Wells' supposed captors—to Marjorie Diehl-Armstrong, seemingly the mastermind behind the failed heist, finds their story within this four-part Netflix documentary, Evil Genius, premiering on May 11 and produced by Mark and Jay Duplass.

The film was 15 years in the making. Co-director Trey Borzillieri began researching in 2003 and he was joined by Barbara Schroeder on the project in 2013. A bomb, bodies in the freezer, houses full of hoarded goods, a scavenger hunt: the story could be said to write itself, but Schroeder and Borzillieri's extensive labor demonstrates that's there's a story beyond that story. No Film School talked to the directors recently about how one goes about wrestling a story like this to the ground.

No Film School: How did you gain access to all of the information for the film?

Barbara Schroeder: I think traditionally, a lot of true crime series might start off with, "Hey, the case is resolved, let’s look back,” but because of Trey’s involvement, as he’ll explain to you, we were able to get a really great, unusual door into this series, right from the start.

Trey Borzillieri: Maybe because I didn’t go to film school was why I had such a naivete about this project. I was in a screenwriting class at the University of Miami when I was encouraged to go see a film at the Cosford Cinema—Paradise Lost. That was the first of the West Memphis Three documentaries, and that really changed my life. I was just blown away by that movie, and for years, I wanted to find the right story, in the hope I could create something like that.

I was in Buffalo, NY, near Erie, the day that this event occurred, and so my jaw dropped. And then a month later, we learned that there’s a dead body in a freezer next door to the dirt road where Brian Wells had made his last delivery, and the FBI was saying that they weren’t connected? That just pulled me right up off the couch and right to Erie. I started filming then.

"It was important for us not to inject our personal opinion about these people."

NFS: When you were gathering all of the information, how was it organized and kept track of?

Schroeder: There was a lot of information Trey had gathered through phone calls, interviews with the police department, visits at the hoarders’ homes, some of whom were coconspirators, all of this great footage. And initially, we thought we would make a bin for interviews, a bin for emails, and so on, and then it gradually became clear that we had to do it by character. First, take this fascinating female character, and let's put all her stuff into one section, for example, and that made it easier to go back later on and assemble.

NFS: When creating a work of this type, an emotional response to your subject is inevitable. How did your possible feelings about these figures affect the way you told the story?

Schroeder: I think you can go down a rabbit hole on this story because there are so many different layers and central characters. It was important for us not to inject our personal opinion about these people.

It was important for us to say, “Hey, let's show you the most incendiary moments of interviews or of progress in this case and also the underlying cases.” We wanted to replicate for viewers the experience we had meeting these people, and hearing about these things, and feeling like, “Wait, no one was ever charged with murder?” We just put out the best moments that we were able to get.

NFS: Given the amount of material, what percentage would you say stayed in the final film?

Schroeder: Well, that interview with Marjorie was very long and very compelling. Man, it would have been nice to have twenty episodes like that. We had to cherry-pick to reflect the best of her. I would say we put in a taste of everything that was unusual that you're not going to see in other films and documentaries, like elusive eyewitnesses who are talking for the first time, or footage of people walking through a water-soaked basement to see if there’s some money hidden.

It was a crazy journey, and I would say we have about 30 percent of everything that we had originally placed in the final film.

NFS: Was there any resistance to your obtaining of this information?

Borzillieri: I’m glad you brought that up, because it was very very difficult. What was on my side, in particular, was that I got in so early. I had a unique perspective because I was there when the case went cold. When it went cold, the question became, “Where am I going to get information?”

There was a gag order on law enforcement. No one would talk. The interviews you're seeing in the documentary were done a decade later or more. All those people waited until they were retired to speak publicly about the case.

It wasn't as if I could lean on law enforcement when I started. To be honest, that's how we ended up with Marjorie. When I reached out to her, she had not been publicly labeled a suspect in this case. That's what enabled me to have such a special relationship with her through the years and capture so much of this, when you couldn't otherwise. You had to go to the actual prisons to capture this kind of material.

Schroeder: Also, on the video we were able to get with Marjorie, she was off-limits to law enforcement. She was in prison undergoing psychiatric evaluation, and they weren't allowed to talk to her, but she was allowed to communicate with people. So, Trey’s letter-writing and talking to her was a really unique way of getting information.

"The idea is that if everything is confusing, going with the simplest way might be the best answer."

NFS: What was the overarching architecture you envisioned for the series?

Schroeder: There’s this theory called Occam’s Razor, I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of it, that speaks to this project. The idea is that if everything is confusing, going with the simplest way might be the best answer. That helped us focus; there are a lot of labyrinths and rabbit holes we could have gone into really easily, and so it was extremely important to maintain a good, strong throughline.

That meant, for example, to talk about the bank heist in episode one, the frozen body in episode two, then discuss the suspects in episode three, and then in episode four, let’s have some resolutions with some new revelations in which we take the case farther than where the FBI went.

NFS: Given its complexity, did you have any sort of working script as you were making the film?

Schroeder: We had a guideline along the way, and then I would interview Trey and transcribe his words, because he’s great at extemporaneous explanations. We had a guide, which was convenient at some points, because you could have a script and then cut up sections and rearrange them on a board, so that we could keep the flow, and the narrative, and make it as interesting as possible.

NFS: How did the planning of the soundtrack fit into that?

Schroeder: We had two composers. There was a pretty renowned composer, Gary Linelli, who did the OJ documentary, and then we had a junior composer, Gage Bazan, who filled in, and whose sound was very much like Gary’s. They worked together to blend everything. We were very lucky to have a senior composer because we could give him a scene or an episode, and say, “Hey, score this,” or Gage would fill in for a very quick turnaround.

That was a secret ingredient, to have a composer who, within an hour, if you said “No, make this three seconds longer!” was able to do that.

NFS: Was there a lot of discussion about the soundtrack?

Schroeder: We liked their style initially, and so we were able to say, “Oh, this should have a Bond girl's feel,” or “This should have a more romantic feel.” There was very little rescoring. These guys nailed it. Both of them were really multitalented, which added a layer of good music, which is a layer of any good storytelling.

NFS: How do you feel the film redefines the word “genius” conceptually?

Schroeder: Well, we had a lot of different working titles, and then in one of the conversations with Marjorie, she was protesting, and she said, “I’m not some evil genius…” and then both of us thought, that’s a great title. It almost positions the word with a question mark: How were these hoarders and misfits, three convicted felons among them, able to outwit the FBI and leave questions still unanswered? Is that a local question or a national question?

"When we did use it, we tried to blur it quite a bit, to emphasize how astonishing and how tragic it is that this is someone who died publicly, but no one was ever charged with his murder."

NFS: Where do you feel the story fits in relation to the issue of racial bias in the police force? I ask because of a statement made early in the film by the 911 operator who took the original call about the crime, to the effect that he had been surprised a white family was being approached.

Schroeder: It was also a specific economic group that was involved. Three of them were hoarders, one was a convicted child molester… But it’s such a heinous thing that Brian Wells said he was told to say black people did it. We really wanted Lamont King [a police officer] in the film, and he gives one of my favorite soundbites. He says that you know at the bottom of your heart that it wasn’t a black person who did it, but you know they’re going to do it anyway.

NFS: Brian Wells is such a curious figure in the film. On the one hand, he appears very innocent, but on the other hand, he’s somewhat decadent.

Borzillieri: He’s someone who spent his whole life trying to live off stage, if you will, only to die at center stage with a shining light.

NFS: The fact that we have clear films of all that is remarkably upsetting.

Schroeder: Not sure if you noticed, but we tried to use that very strategically and not gratuitously. When we did use it, we tried to blur it quite a bit, to emphasize how astonishing and how tragic it is that this is someone who died publicly, but no one was ever charged with his murder.

For more information on 'Evil Genius,' click here.