Making a Successful First-Person Film in the Golden Age of Personal Storytelling

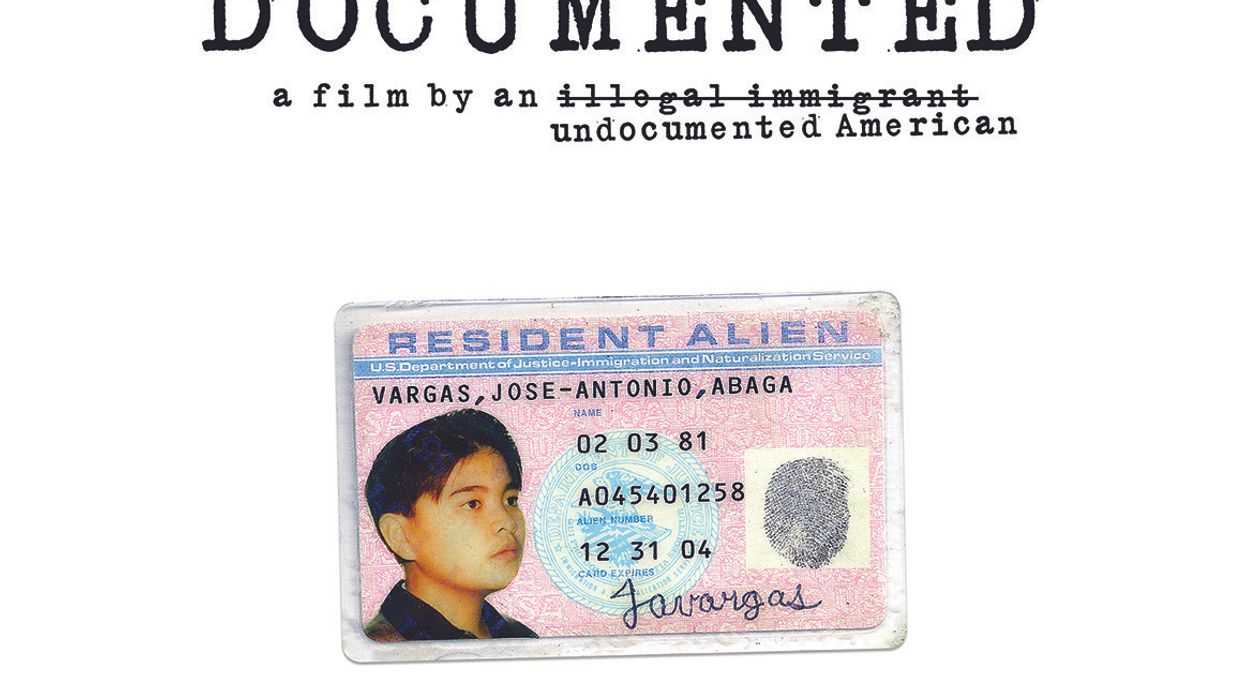

Have you ever thought of turning the camera around on yourself to tell a personal story? What about a personal story that involved outing yourself as an undocumented immigrant and exploring the relationship with your mother you haven't seen in about 20 years? That's what Pulitzer Prize winning author and filmmaker Jose Antonio Vargas did in his latest film, and it wasn't easy. In the NFS interview below, Vargas talks about anything from writing first-person narration, to earning the right to be on camera, to achieving that delicate balance needed for a successful first-person story in his film Documented, which opens in theaters this weekend.

Personal films -- when done well, they can be some of the most resonant, poignant stories on-screen. When done not so well, they can be self-serving films we love to hate for, as Jose Antonio Vargas characterizes it below, their "cringe factor." When he was 12 years old, Vargas got on a plane from Manila, Philippines to Los Angeles, CA. After having built a career as a journalist for such publications as Rolling Stone, the Washington Post, and the New York Times, he decided to make a very personal film about his life and his relationship with his mother, who he hadn't seen since he landed at LAX over 20 years ago. Check out the trailer for Documented and what Vargas shares with No Film School about his creative process below.

NFS: You've made a film that's about immigration, but is also an intimate story you about trying to understand your family and your mother. Personal stories are so difficult to make! What made you decide to take this route? What do you see as the value is in a film that becomes personal?

Vargas: I was most definitely very scared about doing a personal film, about turning the camera on myself. I just wasn't sure. There are so many pitfalls when you do that. It can easily be self-aggrandizing, it can easily be the cringe factor, you know, when you watch a personal documentary. Especially now that we've gotten accustomed to this reality television show -- what is authentic? What isn't? What is staged? Now there are always these questions about authenticity. The camera is a really good bullshit detector, especially with documentaries. I just wasn't sure I wanted to subject myself to that. And I wasn't sure I wanted to subject my family to that. The moment you put a camera on somebody, it says, "Look at this person, listen to this voice, empathize." But it also says -- "Judge." And I frankly wasn't sure. After the Dream Act failed in the senate, I knew I was done, that I had to come out [as undocumented].

I knew I wanted to make a film, because I've always wanted to be a filmmaker. I mean, before I was a journalist, I wanted to be a filmmaker. Writing for me was a way of being on a piece of paper. If I could see my name on a piece of paper, I could prove to people that I exist. But filmmaking, as any immigrant could tell you, we learn about America by watching television and movies. By the time I was in middle school, I had watched every Sydney Lumet, every Frederick Wiseman. The Mountain View Public Library and the Los Altos Public Library were like my biggest theaters. Thank god for all those free movies -- instead of a Blockbuster! And so, I knew that I always wanted to do films.

My original idea before I even started filming was Inside Job meets Immigration. I thought Charles Ferguson did such a great, masterful job of making an argument. He connected the dots and he made an argument. I thought I was going to do that. I started looking through C-SPAN footage, looking for really rogue politicians when it comes to this issue, who I won't name here. But then I started wonder, "Do I really need to politicize and already overly political issue?" I realized, I didn't want to do that. Then I thought, Waiting for Superman. In my original conception, the film would have ended with the New York Times photo shoot. None of my family members would be in the film. It would simply be: follow 5 other young undocumented Americans from around the country to tell their stories, and when I come out in the NY Times, the film is done. For me, I would have loved that, because I'm already privileged to have had a 4,000 word essay in the NY Times. How many people get to do that?

So, I would have considered that I already told my story, so my work here is done. But your life always interrupts your life. Everything changed when I found out I didn't qualify for the Obama Administration program [to get citizenship]. So, that's when it changed. I had to make the decisions. Do I send a camera to the Philippines? Can you imagine that phone call with my mother? "Hi mom (who I haven't seen at that point for about 20 years). I'm about to send a film crew. Talk to them!" And the dynamic of the relationship too -- like a lot of immigrants, I support my family overseas; I financially support my mother. And I didn't feel like because I'm supporting her, she shouldn't say what she really feels.

NFS: So what was your strategy to navigate this complicated dynamic between you and your mother?

Vargas: I remember when the crew got there. Really, I have to give big credit to Clarissa De Los Reyes. She was the DP and also a Co-Producer on the film. She speaks Tagalog. She had the job of really making sure -- not only did she have to shoot it -- but she had to set the tone for my mother. Filmmaking is the ultimate collaborative art. So she set the mood. Afterwards, my mother called me, and she said, "What if I say things that you don't want to hear?"

NFS: And what did you say to her?

Vargas: What am I supposed to say? Should I censor her? "No, mama, say what you want to say. This is your chance." Never mind, by the way, that I've never seen my mother on camera. How is she going to look? The level of empathy, the level of judgement? How is it going to connect? Communication without connection is like -- popcorn, empty calories. So once the footage came back -- they went to the Philippines over Christmas -- that was one of the hardest two weeks in my life. This woman in many ways has been such a ghost to me. It would be so much easier to put her in a file cabinet in my mind and lock it up, and just keep going. All I've ever done was found out I was undocumented. I started writing, because that was a way to exist. I just kept writing and I just kept running. I kept running away from the government, I kept running away from my family, and I kept running away from myself. And now here she is, I'm watching her on the computer. In that beautiful, rich texture of the shot. And she just devastated me. It wasn't until I saw her that I started seeing myself. Who would have thought? To think that a film could have connected me to my mother -- there's something beautiful but surreal and heartbreaking about that. I have seen more of my mother through the editing process of this film than in the past 20 years.

You know what movie was really important to me? Stories We Tellby Sarah Polley. I think every documentarian, every filmmaker who seeks to explore their owns lives, that's one of the first films he or she should look at. It was liberating. I saw that and I was like, "Okay." Every piece of masterful filmmaking opens doors for other filmmakers. To me the most compelling layer of my film is the relationship with me and my mother. And to your original point, personal films are really hard to make, because are we really going to subject ourselves to imperfections? And flaws?

NFS: Not to mention, subjecting your family members to their flaws, which can't be easy.

Vargas: See, yeah. I can handle anything. I have thick skin, I can handle criticism. But to subject my own family, my grandmother, my mother? How dare you judge my mother! Of course, I judged her for so long when I was young, because I didn't understand why she did what she did. When I finally realized why she did it, i realized she had made the ultimate sacrifice. And now I'm going to put her in the film? And subject her to the same judgement?

NFS: Not being in the room yourself for the interviews, what did you tell Clarissa to ask your mother and your grandmother?

Vargas: I had a list of questions I wanted answered. This is where my background in journalism comes in. The biggest gift journalism every gave me was empathy. So I gave them a list of questions. And Clarissa did the interviews in Tagalog. A third of the film is in Tagalog, which is something I'm very proud of. When CNN airs the film by the way, I'm not sure if Primetime television has heard this much Tagalog! I told them, no holds barred. While we were filming, and while we are editing, the goal here is to arrive at some truths. And the goal here is to embrace as much complexity as possible. It's not about making myself look good. Believe, if that were, I would never have done this!

NFS: You're on camera a lot in the film, which is not something you're unused to as you've been on CNN and even The Colbert Report, for example. It's not like you're not acting, because you're obviously playing yourself.

Vargas: I think it works because it wasn't really about me, it was about them. There are scenes where I'm in Iowa talking to voters, and a scene in Alabama with a drunken guy and a farmer. There are the most journalistic scenes, and it wasn't about me. It was about them exposing their reactions to me.

NFS: But for so many filmmakers, it's really hard to be on camera and be natural. You are very successful at that. Like, you see your mother for the first time in 20 years over Skype, on camera. How do you commit to that and do that right?

Vargas: You know, you guys, I read No Film School and it's like the ultimate insider's site, so thank you for asking that question, because I do think its an important question for people to ask. To me, in a way, it's the golden age of personal storytelling. The technology, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter. As a writer, the 3 most dangerous words have always been: I, Me, and My. Those three words have always been very hard to use as a writer, because I feel like to use them I need to earn it, so it's not overdone, not overindulgent. I really have to ask myself, "Why am I saying this?" I think the same standards have to be applied in front of the camera. What am I trying to get across, and how can something so specific be universal? The film is so personal and intensely specific. That specificity allows for universality. You have to ask yourself when you're doing those, when you decide to turn the camera around, the question becomes, "To what end?" For example, are you really the best person? The next film I'm working on this fall, I'm really looking forward to not being in front of the camera. The producers were like, "You work in front of the camera!" But I was like, "No, only if it is really warranted."

NFS: With this writing background of not using I, Me, You, how was it working on a film where you had to write a lot of first-person narration?

Vargas: That was really hard!

NFS: And you're a Pulitzer Prize winning writer, so you're obviously a good writer! But I'm sure writing first-person narration was very different. What was that process like?

Vargas: It was completely, utterly different! Filmmaking is the ultimate sensory experience. There's some things I wrote on the page to read as narration that, once I recorded it and put it in the film, once I heard it and saw it with the image I was like, "Oh no, no, no." So we went through several voice over passes. At first, I was worried it would be talk-y. But I thought of films that I watched when I first got here at 12-years-old, like for example, The Joy Luck Club. There you have 8 Asian American women telling their stories. For me, rewatching that was useful, because I was reminded how that could work. Janet Yang, by the way, who was a producer on that film, was a producer on this film.

NFS: The film's about to be seen by a lot of people. How do you prepare your family for the attention from showing this intensely personal story on such a big screen?

Vargas: My mom has seen the film, my family has seen the film several times. You just have to not be afraid of the truth. You can't be afraid of the imperfections and idiosyncrasies. You have to embrace complexity in each other. I'm more than pieces of paper, and this fight is about more than pieces of paper.

NFS: When you show a film, there's always people who love it and hate it, but when it's this personal, how do you prepare yourself for that negative criticism? Especially if it's directed at you, personally?

Vargas: I have a friend who asked me recently, "How are you going to deal with the reviews?" And, you know, I'm used to editors telling me that it's not good enough. I'm used to editors coming to my desk and saying, "This is not your best." I'm used to being criticized! But, there is something I have to prepare for, which I've just starting to think about. I'm talking to you from Cincinnati, Ohio, and last night, we showed a special screening of a film at Miami University, around John Boehner's district. It's kind of a conservative place. A young woman, this amazing woman, after she saw the film, she said, "Ok, um, how are you going to prepare yourself for the $%#&!! storm that's about to hit you?" She said she liked the film, that she was disarmed by it because she didn't expect the level of intimacy. And she said, "How are you going to prepare?" And I said, "Um. Shit. I don't know!" I hope that people realize that this is one story, it's a 90-minute film. I just hope that in whatever way, it can provide a level of connection that is so needed in an issue that is so polarized and political and misunderstood. I went for that intimacy with the film, because I think immigration is about families. And that's what it's always been about. People come here for their families.

That's what I love about the film. After being in writing, to now work in a medium that's so literal, where less is more. Less is always more. I find that sometimes in personal films, more becomes more. I watched a lot of personal films while I was making this film. I was trying to look for a cinematic language that was intrinsic to me, because I can't be what I'm not. I'm not Michael Moore, I'm not Sarah Polley -- I'm me. And I want to earn the right to be called a filmmaker.

---

Thank you, Jose!

If you'd like to see Jose's personal journey in Documented on the big screen, checkout the list of theaters where the film is playing, and head to the official site to find out more.

- May 2: New York City, NY Village East Cinema

- May 9: Los Angeles, CA Landmark Regent Theatre

- May 9: Tempe, AZ Harkins Valley Art

- May 15: San Francisco, CA Roxie Theater

- May 16: Berkeley, CA Rialto Cinemas Elmwood

- May 16: Sebastopol, CA Rialto Sebastopol Cinemas

- May 23: San Diego, CA Reading Cinemas Gaslamp 15

- May 30: Seattle, WA Grand Illusion Cinema

- May 30: Washington, DC West End Cinema

- Jun 5: Miami Shores, FL O Cinema Miami Shores

- Jun 13: Chicago, IL Gene Siskel Film Center

- Jun 20: Denver, CO Sie FilmCenter

Have you ever attempted pointing the camera at yourself or your family members to tell a personal story? What works for you, either in films you've made or you've seen?

Link: Documented the Movie -- Official Site