It's NOT All About Story: 'This May Be The Last Time' Director On How Oral Cultures Influence The Language of Cinema

Story is everything. Or is it? As filmmakers, we hear this adage repeated all the time, leading us to think the perfect inciting incident or plot twist is what it takes to put together a good film.

As someone who grew up steeped in the oral storytelling tradition of the Muscogee Creek and Seminole, three-time Sundance filmmaker Sterlin Harjo (Four Sheets to the Wind, Barking Water) suggests it's more about how you tell the story, something like storyteller is everything.

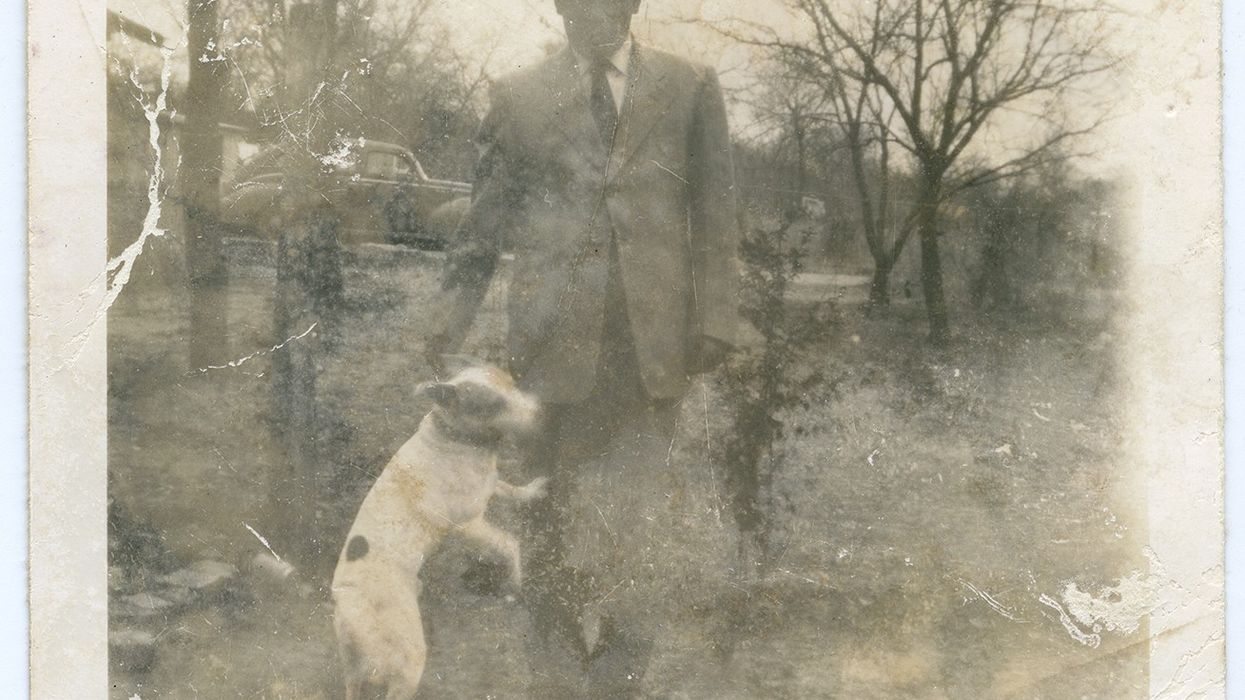

Mixing archives with today's Creek and Seminole of Oklahoma on a Canon C100, This May Be The Last Time traces some of the earliest music in America through traditional Muscogee hymns. From listening to his family tell stories in the kitchen, avoiding cheesy Native American stereotypes, and the differences between making narrative and documentary film, Sterlin sat down with No Film School to discuss his latest film and first documentary. Take a peak at This May Be The Last Time (which you can now see in full here) before you read the interview:

NFS: How did you become a filmmaker?

Sterlin Harjo: I'm from a pretty small town in Oklahoma, and I really didn't know making films was an option. It wasn't on my radar at all -- I was just a really big fan of films. Me and my dad watched a lot of, funnily enough, war movies. I grew up on war movies! I wasn't really censored at all, I could watch anything. I was always a big fan of movies. I was a visual artist — I was the kid in school who could draw. If someone needed something drawn, I was the the one who could do it. So I always knew I would be an artist. I thought I would be a painter. I just sort of made up my mind I'd become a painter. I went to school at the University of Oklahoma for painting. At some point, during that process, I got encouraged about writing. I had written a short story in my remedial English class, and the teacher really liked it and asked me if I would read it in front of the class. That was the first time I really got any sort of praise as a writer!

At some point, I watched three movies at the same time: Smoke Signals, American Beauty, and Good Will Hunting. Those aren't my favorite films in the world or anything, but it was like the first time I had seen films where I could tell who the filmmakers were behind it. I just hadn't been exposed to other kinds of film or anything, or foreign film, in my hometown. So, after I saw those films, I decided to write a screenplay. So I started writing a script. A friend of mine who lived next door was the head of the film and video department [at University of Oklahoma] and one of my buddies was like, you should talk to that guy, he knows about film. I gave my script to him, and he liked it, and encouraged me to take intro to film and video studies. So I took intro to film and video studies with a teacher named Misha Nedeljkovich and he has a love for film that was so contagious. He was a great teacher. I just fell in love with it after that. I was exposed to Truffaut, Cassavettes, Jarmusch, Eastern European films. I was exposed to so much in a short amount of time. And I think that finding out that cinema is a language with the camera got me excited about it. So from that point on, that's all I did and that's all I wanted to do and work towards.

NFS: You mention in the film how Seminole and Creek history isn't written, it's spoken and sung. How do the Seminole and Creek view filmmaking then?

SH: Well it's a rural community, you know? Younger Seminole/Creek people have told me that they got into filmmaking because of me and my films, and that's cool. I just feel like film is an extension of that oral tradition. Instead of sitting around a campfire or in a kitchen telling stories, it's very natural to tell stories with a camera. I think it's tied in really closely to the way we [Seminole/Creek] tell stories.

NFS: Within the film world, there are these rules we try to follow about three acts, and a climax, and so forth. When you talk about cinema being a language with the camera, since you straddle both wider American culture and the Seminole/Creek culture, what do you think about the rules of filmmaking and storytelling that we follow? Do they transcend cultures?

SH: I think essentially all good stories have a similar structure. I mean, I never start out thinking okay, here's my story in three acts. But then, at the end, I look at my films and they naturally follow three acts. So, I think that good storytelling is good storytelling and I don't really pay attention to actually trying to fit within that structure but all of my films I think I can look at and say, hey there's an act, there's the next act. Some of my films are very plotless, and I don't concern myself with that very much. I think that filmmakers every now and then break this inherent mold. People that are stuck in the thinking that films can only be told a certain way are going to be disappointed, because someone will come along and change that, successfully.

I think filmmaking is an exploration and we try to evolve. It's a really young form of art and its evolved so much from the beginning. And it might keep evolving until something new comes along — like telepathy or some sort of chip in our brains where we can make our own movies up there.

NFS: For a lot of people, to tell a story about your own family and to include yourself is very difficult. What was your experience?

SH: It was cool. I knew that the film would be really personal more than anything, just because it's really close to me and where I grew up. I think the hardest part for me was including myself in the film and making my story bigger. Initially, it was never going to be narrated by me. But as the editing went along, it was obvious that I needed to be a part of it. The key was to make each segment work — the film would have three different segments of the story. It was about my grandpa, but it was my story about my grandpa. And my stories that I've heard about my grandpa. I get to retell it, and also have the people involved tell it. You know, it wasn't that big of a deal. As soon as I asked my grandma, and she was cool with it, then I was fine with it. My other grandma had passed away and I had heard her favorites songs. I feel like it was a love letter to my family and my community and how they tell stories.

I think they are very sophisticated in how they tell stories. I tried to mimic that with my film. In my family, you'll sit around the kitchen and listen to them talk and tell stories. It's not like a cheesy, "Indian story time" it's just like people sitting around the kitchen talking. But the way they tell stories is amazing.

NFS: Does that background of storytelling inform how you came up with your narration for the film?

SH: In the film, there's a lot of stuff to cover and a lot I left out. The narration helps bridge those gaps and explain things I needed to explain. Meanwhile, that narration was written over and over and over. I was showing my film in Northern France, and my girlfriend and I were there. It was like one in the morning, and I'm recording voice over. And it's probably the fourth time she'd heard me do it. Constantly revising and constantly changing and trying to hit the right note and the right tone. I even watch the film now and there are a couple of things I would do differently…you know, one or two lines! My accent is probably less noticeable than anyone else in the film, but it's still there. I love that. I love that you have all these different people with country accents.

For me, it puts you in a place immediately. I feel like people in rural America, and specifically the South, I feel like we are this underdog of culture where even though the greatest art has come out of the South, whether it be blues or jazz or whatever. There's still this stereotype of Southern people being, basically, idiots. For me, it's exciting to be able to share these amazing people with country accents. It puts you in a world you're not used to being in. I like sharing these variations of the Oklahoma accent.

NFS: How did you find the different people in the film that weren't your immediate family and gain their trust?

SH: Well, it's a small community. I mean, it's big but it's small at the same time. I grew up in this community. I grew up going to many of the churches that are in the film. And the people that I didn't grow up knowing, they knew my work. They know Four Sheets to the Wind and Barking Water. Those films are really popular in the Muscogee Creek and Seminole community because it is about us. So they're proud of me and they know my work. They know that I'm not going to screw anyone over and they can trust me. I couldn't have made this film first. This could never have been my first film because I wouldn't have had that trust. Making it at the point that I did in my career made the timing right. I was also the producer of the film, I scheduled all the interviews, and I knew it would have to be that way. I knew that community, and I knew it would have to be by word of mouth. I put out the word out that I was searching for people. People would call me and say I should talk to this person, or this person. And I just knew that's the way it would have to be because it's a different world. It's not a world where everyone has their google calendars out and will be here at a certain time. I'm still like that! So the way I scheduled the film was like very, okay when are you available? Maybe Friday or Saturday. Okay, I'll call you in a couple of days and see if that still works. And maybe that changes or maybe it doesn't.

My crew knew going in that this was a different way of doing things and we had to be like that. You'll schedule a shoot at one o clock. Well, the first thing they're gonna do is feed you and talk to you. So you have to allow an hour or two to eat and talk before any cameras come out. And that's just the way we had to do it.

NFS: You've made both narratives and documentaries. What's the difference for you between the two types of filmmaking? Do you have different filmmaking philosophies about them?

SH: I approach documentary and narrative pretty much the same way. I'm just trying to tell a good story. Whatever that story is, everything grows from that story. The way I shoot it, the way I look at the whole film comes out of that. For me, there's not a big difference. I probably couldn't make a documentary where I'm having to follow somebody for thirteen years, there's no way. But this was a small contained documentary that I could make, and I enjoyed that.

It's the same for me, exactly the same…except the editing process. The editing process of a documentary is a nightmare! Editing a film that I wrote is so much easier, and I know that now.

After I made this film and it premiered at Sundance, I went right into making another film. And I'd written it, and it was so much easier to have a specific number of scenes I had to deal with. But the way in which I make films is very similar. The way I make a documentary, it's like working with an actor. You're looking for a good performance. You have to ask the right questions to get that performance, and give them the space to give that performance, to tell stories and live their emotions out. It's just like working with actors except more spontaneous and on the fly. You have to really think quick and go with the flow.

NFS: What does it mean to be a filmmaker and be Native American?

SH: I'm excited because no one has done it. I get to explore and do things with a type of story and characters that no one has ever seen. So for me it's about that. There's not a lot of funding and there's not a lot of money. I mean there's a stigma that native movies don't make any money. You have to be true to yourself and true to the story you want to tell. I find it exciting, telling stories that haven't been explored.

SH: My advice is to just make films. That's what I did. Some people get locked into school forever, or locked into being a PA instead of making a film. You can do all that stuff, but don't forget to be a filmmaker. And just make films, because you're going to make shitty films. You need to get those out of the way! And always be learning. I shot a feature in college, I shot about 90% of it. I learned so much by really screwing that film up. You can't really edit one scene together, it's that bad. But I learned so much! What not to do, how to work with actors. It was a really good experience. I made music videos, I made everything I could make. I took a loan out I'm still paying off to buy a computer and a camera, and I taught myself to edit. And I think that's what you have to do. If you're serious about it that is. I mean, life is short. You want to make films, you need to be making films.

***

Thank you, Sterlin!

If you want to check out This May Be The Last Time, it's now available on iTunes and Google Play, among other things. Find out all the ways you can see the film, including in a theater, on the This May Be The Last Time official site.

Do you have experiences with storytelling across cultures? Have you learned anything from listening to the way your family tells stories?