Watch: How Italian Neorealism Brought the Grit of the Streets to the Big Screen

Filmmakers like Visconti, De Sica, and Rossellini ushered in the raw, unfiltered reality of Italian Neorealism.

[Editor's Note: The following introduction was written by Max Winter.]

Italian Neorealism is, in many ways, a sister movement to the French New Wave. Like the French, Italian filmmakers felt the need to grapple, in their own way, with the political realities of the world around them. In the case of the Italians, the main reality to be dealt with during the 1930s and 1940s was the reign of Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, and this insightful new video essay by Tyler Knudsen shows how the Italian Neorealist movement did just that.

The films became instantly indelible for their faith to timeless, universal problems and age-old stories.

Though Mussolini provided for film as an art form during his tenure, such as financing the construction of the great Cinecitta Studios and establishing the Venice Film Festival, Mussolini also placed strictures on its content, both directly and indirectly. Thus, the films that were produced during the Mussolini era were light, unchallenging and not terribly moving—essentially soap operas—called "white telephone" movies for the white phones which kept popping up in their upper-middle class settings.

A group of Italian film critics, all published in a magazine called Cinema, wanted to make a different kind of movie. They wanted film to show life as it was lived by ordinary working people. They wanted to show these people grappling with large, sometimes unsolvable problems, sometimes coming from their own lives, and sometimes stemming from larger social structures over which they had no control. And so the films that grew out of the Italian Neorealist movement became instantly indelible for their faith to timeless, universal problems and age-old stories.

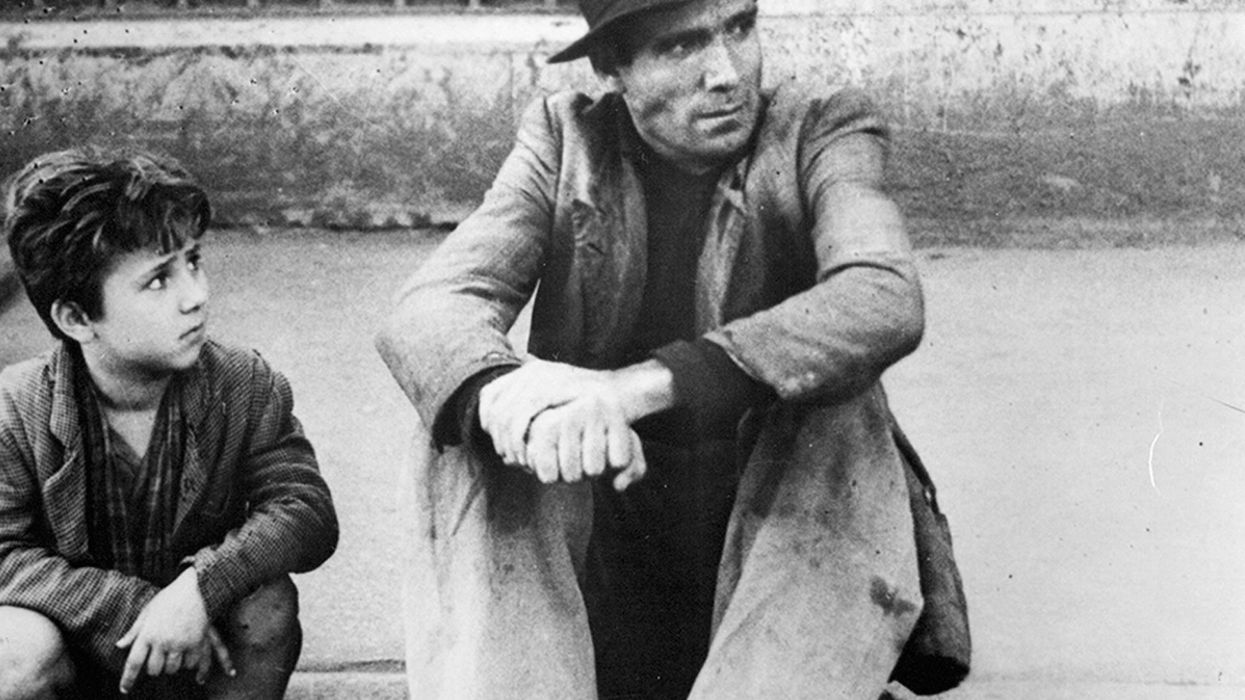

The most famous Italian Neorealist film is Vittorio De Sica's Bicycle Thieves (also known as The Bicycle Thief). The film tells the story of a man whose bicycle is stolen; the loss is crushing for him, because he uses it in his daily livelihood and needs it to support his family. The actions he takes to right the situation are as tragic, if not more so, than one might expect, but, simultaneously, true to human life.

Sometimes, to tell the grandest of stories, you must focus on seemingly mundane details. These, in time, tell their own story.

Another cornerstone of the Italian Neorealist movement is Roberto Rossellini's Rome, Open City. This film was actually shot during World War II, making the conditions of its production highly arduous and unusual. Imagine filming a movie during wartime! Rossellini had to buy the film he used to make the picture illegally, on the black market. But his striving paid off: the resulting work, a tale of romance and danger among Resistance fighters, is widely considered to be one of the greatest films ever made for its historical, daily, and emotional accuracy.

One of the earliest Italian Neorealist films, Luchino Visconti's Obsession, was censored for its cinematography. Rather than using the high-glam closeups favored by movies of the time, Visconti chose to use only medium and wide shots, so as to include more stark details of the world he was filming. As a result, the government made sure the negative was eliminated; we only have the film to watch at present because Visconti had made a copy of it. As you watch this gripping history of Italian Neorealism, remember this: sometimes, to tell the grandest of stories, you must focus on seemingly mundane details. These, in time, tell their own story.

Movies referenced

- Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948)

- Bitter Rice (Giuseppe De Santis, 1949)

- La casa del paccato (Max Neufeld, 1938)

- Obsession (Luchino Visconti, 1942)

- Paisan (Roberto Rossellini, 1946)

- Germany, Year Zero (Roberto Rossellini, 1948)

- Journey to Italy (Roberto Rossellini, 1954)

- The Earth Trembles (Luchino Visconti, 1948)

- Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945)

- Shoeshine (Vittorio De Sica, 1946)

- Umberto D. (Vittorio De Sica, 1952)

- Stromboli (Roberto Rossellini, 1950)

- Miracle in Milan (Vittorio De Sica, 1951)

This video essay, a collaboration by Press Play and No Film School, is the third in a series on film movements, their histories, and their enduring influence. Familiarity with movements of the past is crucial to the understanding of current cinematic trends. Watch the first film in this series, on German Expressionism, or the second, on the French New Wave.