Watch: Sex, Nudity, and Why You Need to Get Actors' Consent

To become a respected director, start by respecting your actors.

What is the nature of the relationship between a director and a film's actors? Is it that of the employer and the employee? Is it that of colleagues, working together toward a goal? Is it the relationship of a perpetual student and a wise teacher? Or is it none of these? Whatever the case, it's safe to say that both director and actor have rights, as humans. Film history reveals a myriad of cases in which, caught up in the intensity of a film, a director might violate the rights of an actor, without necessarily thinking that's what he or she was doing. This excellent new video essay by Ivana Brehas gives two solid examples of cases in which an actor's rights were violated. How? By using the actor's body as a tool without the actor's express consent.

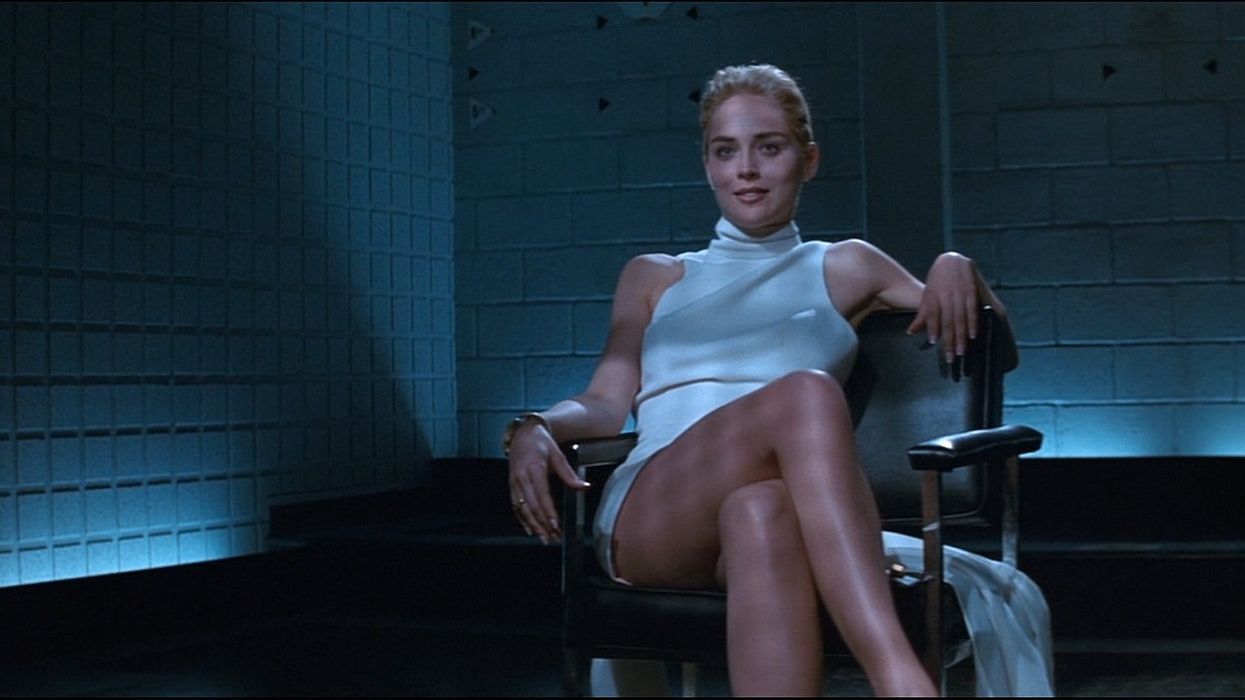

The first scene discussed is the widely-watched, much-talked-about, no-longer-that-scandalous-but-a-shocker-when-it-came-out scene in Basic Instinct when Sharon Stone flashes a room full of police interrogators as she uncrosses her legs. Director Paul Verhoeven apparently staged the shot without making Stone 100% clear as to its content, saying her underwear was distracting, having her take them off, and then showing her the rough cut on such a small screen where she couldn't tell the extent of what was shown. By the time Stone saw it, it was in theaters, larger than life, and out of her hands. Granted, it's a provocative scene, and probably in retrospect the most interesting scene in the film, in terms of its shock value. But—and this is a large point—it was filmed in such a way without the actor's express consent; knowing this lessens the scene's impact, at least for this viewer. From the director's perspective, one does what one can to make a moving, intense film experience—but shouldn't there be limits to that "what one can"? What does it say about you as a director if you can't elicit realistic performances from your actors without deceiving them?

"A director must maintain ethical standards that still allow the artistry of the film to flourish."

The more egregious example discussed here is the famous rape scene from Last Tango in Paris. Neither director Bernardo Bertolucci nor Marlon Brando, the film's male star, told Maria Schneider what the explicit action of the scene—violent anal sex—would be before it was filmed; as with the Verhoeven film, she was kept slightly in the dark about it until it was too late for her to resist. The scene was realistic, obviously, and, for many viewers, it might be the only scene they remember. But at what cost? A substantial one, it would seem. Schneider—who was only 19 at the time to Brando's 48—remained scarred by the experience until her death, as well one might be.

There are obviously cases in which keeping actors guessing about the scenes they're filming could help a film, keep it spontaneous, give the work a mood of excitement it might not have otherwise. But it goes without saying that a director must keep his or her judgment in good check, and maintain ethical standards that still allow the artistry of the film to flourish. For the good of the entire industry, let alone your own reputation, get consent from your actors before having them engage in any kind of nudity or sexual behavior. For some best practices on how to do this, check out our Indie Film Weekly episode on the topic (at 27:25).