When Will VR Have its 'Jurassic Park' Moment?

Filmmaker Stephen Steelman on how creating in VR is a wide open playground, especially when you still need to find your audience one viewer at a time.

When filmmaker Stephen Steelman transitioned from acting to behind the camera several years ago, he found his first footing with music videos and live event graphics for bands including the Deftones, Sad Robot, and Westfield Massacre. As he expanded into digital animation and game creation, he fell hard for telling stories in virtual reality. We spoke with Steelman about the process of creating, and then exhibiting, projects in VR as he prepares to launch his VR short, A Challenge, on Steam. A Challenge tackles some of the complications of VR production by building its story around a second person observer—the victim of a kidnapping—and ultimately takes full advantage of what VR has to offer.

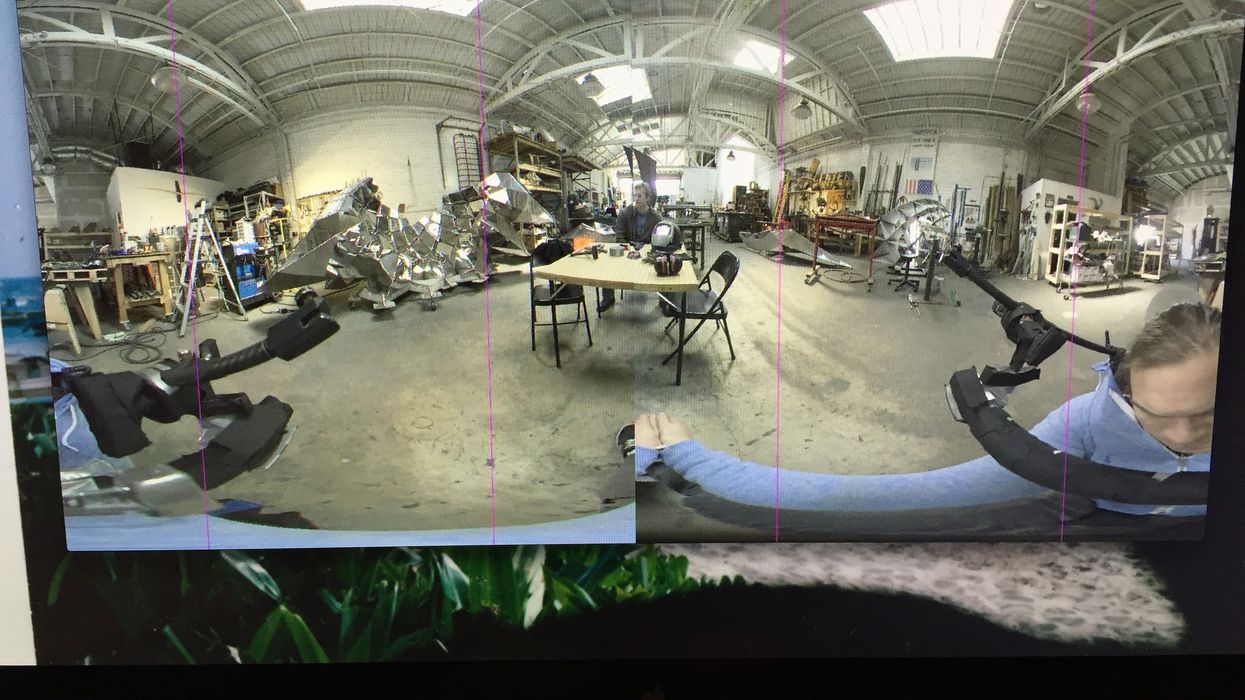

"We built a POV rig and then I was the body in the shoot, so that way I could see what the actors were doing."

NFS: How did you first decide to kick off with VR?

Stephen Steelman: I was working at another company and we were doing some video game stuff, and we acquired a DK2 just to mess around with. I got interested and went to all the seminars and really started nerding out.

I went to one seminar here at Film Tools where this guy showed a couple of those 360 Hero rigs and talked about stitching, and the thing he said, which I always butcher the quote of, is, "If it's a story that you can tell in a screen medium, there's no reason to just adapt it to VR just because. You need to think of a new story that only makes sense in VR...Use the medium for what it is rather than just adapting." A lot of the VR stuff that you see ends up being stuff that's just kind of people thinking, “maybe this will look cool in VR.”

I got the itch based off of that idea. I saw a bunch of stuff, and then when I was up at VRDC, I wrote a script, and then I talked with my buddy who shoots a bunch of VR, John. I said, "What do you think about this?" And he really liked it. Then three weeks later I was sitting there with an OZO going, "Okay, I now we're going to shoot something and see how it goes."

NFS: What were your experiences with the OZO?

Steelman: It can do some really cool stuff. It's amazing to see a 3D image. It's amazing to have that much data and put it together in OZO's backend stitching software. It made my life so much easier. I heard so many stories about people dealing with the nightmare that is stitching and with the OZO you don't really have to do that. That being said, it's a tech company making a camera and so it doesn't take into account what shooting and physical production is really like. And so, to a certain extent, using that camera, and maybe it's different now, you're kind of beta testing. Things like the ISO resetting every time you turn the camera off...

NFS: Every single time?

Steelman: Every single time. You would hope it would keep that information and, you know, it's not a normal camera where you're really get a sense of the preview, so the only way you can see what you're going to shoot is plugging a laptop into the OZO, which you're probably going want to unplug before you shoot because you don't want to have to paint it out. But also, the OZO only has a 45 minute battery. You're trying to turn the camera off as often as possible. Then you end up having to plug in the laptop to make sure your ISO's right again. It just slows the process down, you know.

The battery is connected to your hard drive; It's called a power module. When I shot you couldn't get more than one of those and downloads take six hours, so you end up having a short day; you're never going to be able to download all the content. You're not going to have another hard drive. I would ask for another take and John (Calabrese) my first AC, would say, "You're going to regret that later on in the day because we're going to run out of space or we're going to run out of battery." I said, "Okay, fair enough. Let's move on." The last thing we wanted to do was not get the film completed.

NFS: There's no wireless monitoring at all? There's no "I open an app on my phone and see a spherical view?"

Steelman: No. There's none of that and maybe things have changed, but I don't think they've gotten that far along. If you want to preview in the HMD, you can. If you want to see the sphericals, you can using the OZO preview app, which is on your laptop, but everything is tethered at this point. What a lot of people will do is they will put GoPros beneath the camera, because then you can pull up the GoPro viewer and at least you're getting sort of a sense of what it is you're shooting when you're shooting it, but if you're like me, you just attach yourself to the camera and make it part of a story and that way you can see what you're shooting because you’re in it.

NFS: So you were the body.

Steelman: Yeah, I was the body. We built a POV rig and then I was the body in the shoot, so that way I could see what the actors were doing.

NFS: Aha, well that's really smart.

Steelman: I mean, that was the only way to really get a sense of what was being shot. Plus, we shot the scenes static as well, where we just mounted the camera to a tripod just to be safe, but you always get better action when the actors can talk to a person as opposed to talking to a stick or a camera, you know?

"You find yourself in a space where you're like, 'I don't know why I'm in this space. I don't know why I'm here. I don't know if I care. I'm not connected to any characters.'"

NFS: Yeah, totally, in terms of the performance. Let's talk about that a little bit. As far as you know, have other people used the technique of building the narrative around a person seated in sort of the audience position?

Steelman: I can't come up with another specific example right now. Obviously, that exists a lot in video games. But a lot of the big narrative stuff has kind of skirted over it. It is an issue that you have to answer: Who is the audience? Who is the camera? What is camera? Is this camera just this floating orb? I think it's important for the VR filmmaker to answer that: Why am I here?

Recently I was talking to John, and he was saying from a DP standpoint you've got to say, "Who is the camera?" You really should be saying that with every film you make. I think a lot of the time, with a lot of the other VR that I've watched, you find yourself in a space where you're like, "I don't know why I'm in this space. I don't know why I'm here. I don't know if I care. I'm not connected to any characters." It becomes that thing where the brain of the viewer is trying to wrap themselves around that information and they're missing any chance to connect to the story.

NFS: Which is interesting because if you compare it to something like video game language, video games often put you into space and you're not entirely sure why, but it doesn't necessarily matter because you have the mission and the mission orients you in the space.

Steelman: Yes. You have the mission. You're also the center character and you can move around in space.

NFS: What you did was an elegant solution by having the bounded nature of your presence make sense because the character is bound.

Steelman: Yes, absolutely. Of course, in the next one I'm working on, I'm trying not to do that again!

NFS: I suppose you can't have your entire career just be movies of kidnappings. It's just a hostage movie over and over again. How many different ways can we tell the hostage story?

Steelman: Yeah, but I think in the next one I'm working on, the character that the viewer inhabits is important to the story line, but isn't necessarily the prime focus. That to me is the difference between video games and live action right now with VR, is that if I make you the central character, I have a lot of people talking at you and the viewer is themselves rather than the viewer.

Think about it: when you watch Die Hard, you're watching John McClane. You're not watching you. Or you're not in that space. If you were in that space you wouldn’t have the backstory that John McClane does. If I can have you as the viewer be like Argyle, for example, in that movie, where you're interested and you're learning about this guy, but at the same time you're not the centerpiece of it. That's the space I'm playing around in where you end up just being more of a secondary character, which might get old too, but I feel like that's what makes sense for me right now.

NFS: That actually makes a tremendous amount of sense to me. Second character POV is sort of an interesting writing challenge in a lot of ways.

Steelman: Yeah. You want to give the viewer some involvement and you want them to feel like they're engaged in what's happening in a positive way, but still finding ways to make it where they care about the other characters. It's tricky. The next one I'm working on has a lot of different challenges. It's like taking things up like six notches as far as difficulty.

NFS: How has finding an audience been?

Steelman: It's a little bit tricky. I've been lucky in that I'm finally getting people to look at it and with some of the distribution that’s available, but it's a little bit closed off. I think you have these companies that have already been in the space for four years and they've been busting their ass, they've been doing really cool amazing stuff and experimenting like crazy. They have financing behind them and they don't necessarily want to open up the flood gates to just anybody. They are a little bit protective, especially because they're not making money so I think they say, "We've invested millions of dollars in trying to make VR work and we're still not generating revenue. We don't really want some new person to come in and take that over."

"Companies like Walmart are doing tons of VR, but it's all in-house to train their employees. That's not sexy if you're a filmmaker."

Some companies have come out of the blue and said, "Oh, you know what? We're going to do some more of the industry type applications for this." Companies like Walmart are doing tons of VR, but it's all in-house to train their employees. That's not sexy if you're a filmmaker. And so, some of these companies were aiming for the big cool narrative pieces that don't really have an audience yet, but then if you're going out and you're doing industrials and you're doing short commercial pieces and stuff like that, those are the companies that are generating revenue and are keeping the lights on.

For me right now, I'm just trying to get it on every distribution outlet which is out there. There's Lens, there's Within, there's Steam, and there's Littlestar [Editor's note: after the interview, 'A Challenge' joined the Steam VR store]. That's kind of all of them. There's YouTube360 and YouTubeVR, but I don't want to release my movie in 360 because it doesn't work in 360.

NFS: We’re still in this weird place with VR where, to be honest, not a lot of headsets have sold compared to projected numbers.

Steelman: But PSVR has sold almost a million units. Gear VR seems to be doing pretty well. It's on its way, and so my belief is that the content has to stay, the content has to get better. I think that everyone's saying, "Well, we need to sell more headsets so we can do more content." And I'm like, "No, no, no. That's the wrong way." The content needs to get to the space where people go, "Holy shit. I need to buy one of these.”

NFS: Yeah, it's always going to be content driving those purchases. You only buy a movie ticket because you want to see the movie. You don't buy a movie ticket because you've heard movie technology is great and you want to see what it might be. You buy a TV because you want to watch “Cheers,” not because you heard TVs are cool.

Steelman: Right, but I do think that in the VR space right now, it feels a little bit like, "Well, let's get more headsets out there before we really take a chance."

NFS: VR is currently being marketed not based on content, but based on technology. I don't think that works.

Steelman: I don't think anyone's cracked the nut of what are stories in VR that are unique to the medium that make you go, "Holy shit." Where's the Jurassic Park moment? And obviously it's not going to start off as a huge 90 minute piece that costs 200 million dollars, but we just need to start finding stories that make people go, "Wow. I need to show this to other people. I need to bring this, I need to get this." There's a great dude out here (in Los Angeles) who got so into it and when he has a party he just sets up his Vive and has everyone try it, but he’s only showing people the games. You want live action stuff to be in the mix with that. You want people to see something and go, "Holy shit. That was really cool."

"The tricky part is that VR is vulnerable. You're vulnerable."

The tricky part is that VR is vulnerable. You're vulnerable. I've shown this to people in their office and before they put the headset on they say, "Um, please don't steal anything." You don't know. You're locked off for four minutes where you don't know what other people are doing. That's why I'm very adamant when people watch my movie to not let their friends fuck with them. I don't respond to questions when people are viewing something. I'm going to let you have your own experience in a safe place because by putting the headset on, you're trusting me. Not just with watching something that you may not like, but you're trusting me with the fact that you're completely vulnerable to anything I would want to do with you. You could cover someone in shaving cream while they're watching a VR movie, you know.

NFS: You've been road showing this.

Steelman: I went to the Lumiere Awards, and hung out in the lobby with my headset.

Mark Lieber got a chance to see it and was like, "This is really cool. You should definitely show it." He was nice enough to invite me and I got to show it a bunch of people. It’s very cool to watch people experience it. I can tell by the viewer’s body posture what scene they are watching. It’s great to see people react and lose their shit when the gun gets pulled out or stuff like that. I forget that is effective and engaging because I’ve spent so much time dialed into the technical. Dialed into “How do I get the blood to look like it's on the wall not floating in mid-air?” Things like that and you forget that the film does create this visceral experience that normal films can’t create. Seeing their reactions really instilled in me the power that this medium has.

"Seeing their reactions really instilled in me the power that this medium has."

NFS: It also sounds a little bit like that great old time cinema experience of doing the test screening where you sit in the back of the theater with four hundred people and watch the joke land. Now you hit the road with your HMD and you're like, "Here's the experience," and you get to sort of observe their physical reactions while it happens.

Steelman: I've probably had, I don't know, 40 or 50 people that I've watched watch it. It's funny when you think of those numbers you go, "Wow, no one's seen this." You learn a lot ....The stuff that we tried to do with this one, we're trying to make it about the story, trying to get the viewer to get engaged with the story and not just look around incessantly because they're like, "Holy shit, guys. Look, it's the 3D VR." I mean, to get people that have never been in a VR movie before engaged and sometimes you see their body posture mimic the body posture of the character they're inhabiting, it's really cool. It's crazy when you see someone who puts their hands together like they're the hostage and they've rounded their back and they're in the same exact position the hostage is in in the scene because they're just into it. That shit's cool.

NFS: What are the big hurdles for VR growth right now, do you think?

Steelman: Well remember that when you talk to a lot of VR folks, they're saying, "The frame rate's getting better. The frame rate's getting better." As a filmmaker, you and I go, "Wait a second. Hang on guys. We want 24." Even when I made this, I said, "We shoot at 24, right?" And they said, "No, you shoot at 30. You really want to shoot at 60. You really want to shoot at 120." But that's video games, that's video game thinking. That's hyper-real, that puts you in a space and coming from the cinematic sense of 24 frames looking the way we want and the motion blur looking the way we want and stuff like that. We need to get it looking cinematic.

And I think the actors are going to have to change. We rehearsed it like it was a play, but that doesn't mean it’s play acting, you know? You get in this issue where sometimes the characters are far away, so it has to feel a little bit bigger from far away because you're not getting the facial expressions. But as we're able to get closer, yeah, you've got to make it read in a variety of ways.

NFS: So actors don't have to learn just how to do stage work and camera work, they need to learn to calibrate their performance to the geography of closeness to the rig.

Steelman: Yeah. I mean, that's the ideal, right? If I can't read your face because you're pretty far way, yeah. I need to be able to get what's going on, so it's almost like how far away are you from the camera? Okay, this is stage performance. Then when you move closer to the camera, you've got to bring it down. You know?

NFS: Which is very hard when you don't have real time feedback, where you're not watching a monitor.

Steelman: Everything is trial & error right now. I think that VR lends itself to really be an actor’s medium. To really be something where actors can sink their teeth in. You're looking at long takes. You're looking at stuff where it's very dynamic and it has to be interesting and you've got to be on. Filmmaking has always been called a director's medium and TV's the writer's medium, this I think is going to be more of an actor's medium and more of a sound designer's medium. And I think we’ll be able to engage with viewers in ways we’ve never been able to before.

Check out A Challenge now on Steam VR.