Yet Another Ode to the Best Shots in All of Cinematic History

Even more cinematic beauty for you to feast your eyes on...

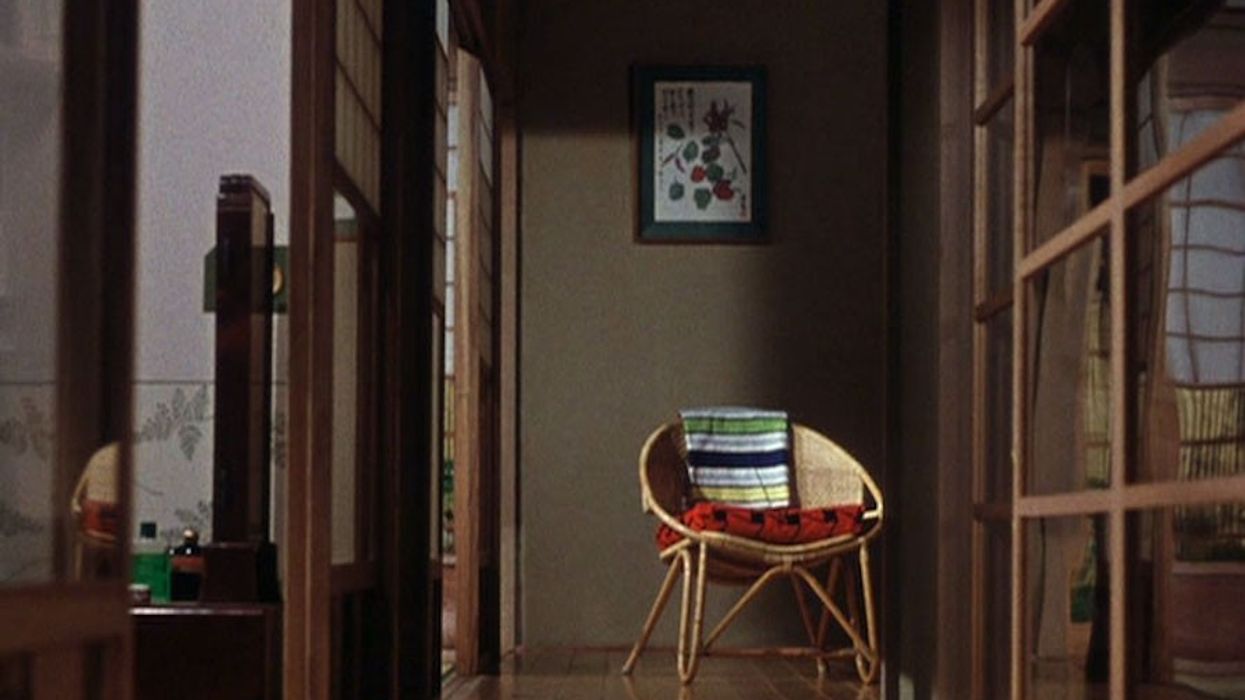

Last week we shared Part II of CineFix's Best Shots of All Time series (and a week before that we shared Part I) and we all got to bask in the glory of our beloved cinematic medium as shots from Paris, Texas, Raging Bull, and The Passion of Joan of Arc played on our respective screens. This time, CineFix has combed through the work of directors like Yasujirō Ozu and Andrei Tarkovsky to show us just how incredible simple establishing shots and cutaways can be. Check it out below:

If you've been following along with this series, I think the lesson we're all beginning to learn is that there is no such thing as an unimportant shot. Every choice you make as a filmmaker, from shot size to camera angle, can have an incredible impact on your audience, so you do yourself and your work a disservice when you don't treat every shot like its a potential masterpiece.

Director David Lean said it best when he said that you should be able to cut any frame out of a roll of film and hang it on the wall. It's true! You should always try to inject as much meaning and purpose into even the most trivial shots, because, as you can see from the video, simple cutaways and inserts can not only add so much to your story, but they can also make a lasting impression with your audience.

Source: CineFix