Why Racial Representation in Film Goes Way Beyond Casting

"Any time a person of color makes a movie, it's an act of revisionism and reversal because Hollywood was absolutely forged in stereotypes."

With Hollywood climbing out from under its worst summer to date, and American racial tensions making the news nightly, many agree that cinema needs a fresh perspective. The success of films like Moonlight and Get Out are proof of this need. And the proliferation of weak attempts at representation in studio casting is proof that Hollywood acknowledges it. This isn't the first time that it has fallen to artists to sway societal trends; the feature film has long been a mode of making the specific experience universal, and thus introducing new ideas to wide audiences.

"Boyhood is widely read as a universal film, whereas Moonlight is read as the queer black experience."

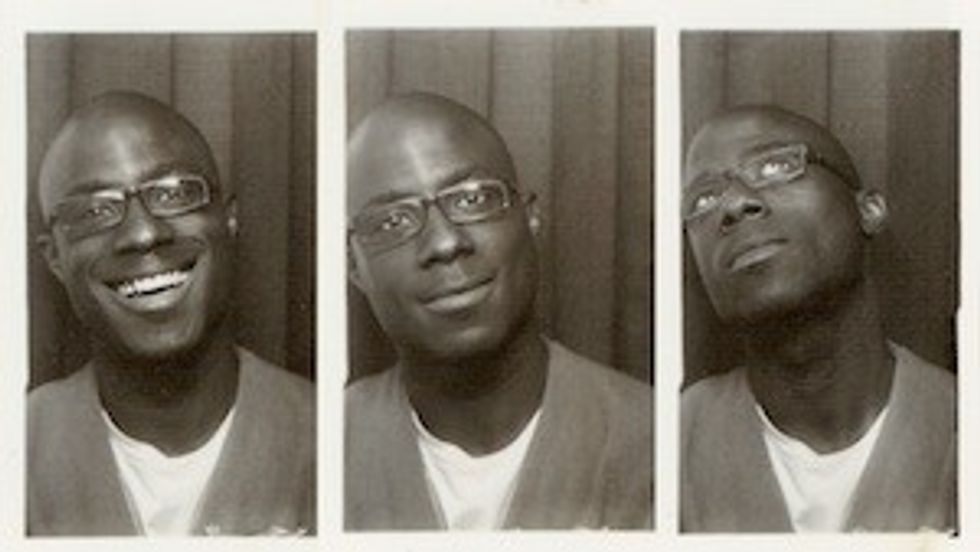

Lincoln Center's New York Film Festival has been a consistent supporter of true diversity—i.e., diversity of perspective, not just optics—and at this year's festival, they held a panel to unpack that difference. Seated on the "Cinema of Experience" panel was Ashley Clark, senior programmer at BAMcinématek, Teo Bugbee, film writer for The New York Times and Vulture, and Farihah Zaman, documentary filmmaker and production manager for Field of Vision. The panel was moderated by Film Comment Editor-in-Chief Nicholas Rapold.

They discussed their favorite films, pushing through your rage to find your voice, and why Kathryn Bigelow is problematic. Check out our key takeaways below.

Diversity in craft

Rather than exploring the tired territory of representation on screen, Rapold asked the panel to discuss their favorite examples of diversity in craft. "How can the craft of filmmaking reflect different kinds of experience?"

Clark has been especially impressed this year by Dee Rees' new film Mudbound. He spoke about the unique way in which the film employed multi-stranded narration. "There are six or seven different voice-overs, which ordinarily is a quite difficult sell." Clark has always approached narration with hesitancy. "I was brought up to believe that voice-over is a lazy tool in filmmaking, it meant that you didn't have the visual acumen to parse out information in other ways."

"But in this context," Clark continued, "with the empathy that the film has, it's an interesting way to convey the inner thoughts of repressed characters who cannot articulate their feelings because of the social conditions they find themselves in."

Making art as a POC is radical AF

"I think it's interesting and makes sense that Moonlight continues to be a part of the conversation around race in film," said Zaman. "I think there's a number of ways in which that movie is really radical."

She commented on the tacit restrictions imposed on certain filmmakers. "There's this idea that if you tell a story about these people, it has to be done in this way." She continued, "When you see movies that are by black people and about black communities, it's almost like it's only allowed to be epic if it's a crime story, for example."

"We talked about that recently with Boyhood," Clark agreed, "Boyhood is widely read as a universal film, whereas Moonlight is read as the queer black experience."

"It's still a radical act to be a black filmmaker, and it's only inherently political because we live in an unjust world."

"What I loved [while] watching it is that it has this epic melodrama quality, and that Barry [Jenkins] gave himself permission to take these auteur risks." Zaman said, "It reminded me that you should be able to make the choices that make sense for your film, and I think that people of color are sometimes less well received when they don't stick to the mode that people expect from those stories."

One thing that irks her, Zaman mentioned, is the onus put on filmmakers of color to make political films. "In talking about the film, [Jenkins] wasn't particularly interested in harping on the political ramifications of making the film that he did. It's one of those things where it's still a radical act to be a black filmmaker. And it's only inherently political because we live in an unjust world."

The calm of specificity

It's not only the sameness in most films today that's turning people off, it's the sheer overwhelmingness of media. Bugbee noted that "the specificity of gaze [in Moonlight] is especially striking."

"The role that movies serve for me, at this moment in time, is being immersed in what feels like a coherent perspective."

Bugbee referred to the exhaustion of wading through the 24-hour news cycle and social media opinion posts. "As we live in a time that feels increasingly chaotic, there is a real meditative pleasure, and a real profound calm even when you're watching something that's very challenging, that comes from being placed into a single perspective that's not your own, that's crafted, that wants you to gain meaning, and not haphazardly."

Appreciating, not appropriating

With respect to the line between appropriation and a valid outsider's perspective, Zaman feels that it is possible for someone from a different culture to approach these topics with respect. How to do it, is partially in the craft. "The Travis Wilkerson film [Did You Wonder Who Fired The Gun?] is a great example in thinking about perspective," she said.

"He had always heard that his grandfather was responsible for the murder of a black man in the rural southern town where he grew up and decided to investigate that." She has definitely seen films, she said, where that becomes a problem. "It becomes about 'this is how I, as a white man, learned to contend with my history and isn't that wonderful for me?'"

The reason why Wilkerson's film is different, is partly being a compassionate and smart filmmaker, but also a result of some very specific aesthetic choices.

"As someone who's been seeing videos of black people being killed by police for the last decade, it made me really sick and I began to wonder why I was there."

"There are these very lengthy interviews of people in the town during that period of time, and I really was struck by that duration, giving that person the voice to speak at length rather than taking the mic back." Zaman felt this was a great example of "how to approach the story from a privileged perspective, but not give the audience the sense that you're continuing to ride your privilege."

"In a lot of the discourse around authorship, there is this idea that a person from a certain group is not authorized to make a film about another group," Clark weighed in. "I don't believe that, and I also think that empathy, curiosity, and compassion are really important, whether it's clear or implicit on a formal level."

As an example, Clark named Nothing But A Man, which was Malcolm X's favorite film, and was directed by a white Jewish filmmaker. "Malcolm X wasn't saying, 'a white man can't tell this story of segregation in the South,' the film was made with such empathy and understanding that it transcends that." However, he said, it's quite clear when a film does not surpass that bar of compassion. "Something like Detroit this year, by Kathryn Bigelow," said Clark, "which I thought was not an empathetic movie and did cause me a lot of trouble."

Why Detroit is critics' problematic fave

"For anyone not familiar," Clark went on to describe the film, "it is an epic re-staging of an incident that happened in '67, in Detroit. There was an uprising in response to police violence against African Americans."

Of course, Bigelow did what she does best, which is played up the tension and violence. All told, "it's about 90 minutes of full on graphically depicted violence against black people by the police. As someone who's been seeing videos of black people being killed by police for the last decade, it made me really sick and I began to wonder why I was there."

"When that film came out, there was a profile that was done in The New York Times of Kathryn Bigelow in anticipation of its release," said Bugbee. "In this piece, she's asked why she wanted to write the movie, and she describes basically being passed the script and her response was that 'I don't know that I'm the right person to make this movie,' and was sort of convinced by the people around her that she was, and started in on the process from that point."

She added, "I think that that is probably not the best way to come to a project like Detroit. Ultimately, you're watching a movie that a filmmaker felt like they should make, not that they wanted to make."

Use your rage, but don't lose your voice

In fraught political times, it can feel inviting, necessary, or even like a responsibility to use your art to speak out, but in doing so, it's important to maintain your artistry.

"Particularly in the documentary community, there's this immediate feeling of, 'what am I going to do about this?'" commented Zaman.

"I always had this chip on my shoulder about the way in which people conflate documentary filmmaking with journalism and activism. I'm very happy for activist filmmakers, but I don't want the onus of activism placed on me simply because I work in a non-fiction mode." She continued, "Making an explicitly political piece of work shouldn't have to mean that it's inherently told in a very blunt or traditional way. Don't lose your sensibility simply because you have strong emotions."

"If you're living in Europe you're aware of the migrant crisis, it's a serious issue, but how do you approach it if you're a comedy filmmaker?"

"The Aki Kaurismäki film, The Other Side of Hope, is a great example of that," replied Bugbee. "He's Finnish, and it's about a Syrian refugee who winds up in Finland and is trying to secure his status as a Green Card holder. The movie has this same arch tone as his other work, there are very bright primary colors, the stilted frames that suggest comedy before there's actually a joke."

"It is interesting to watch filmmakers who you wouldn't think of as especially political, apply a style on top of the issues that are sort of unavoidable." Bugbee wondered, "If you're living in Europe you're aware of the migrant crisis, it's a serious issue, but how do you approach it if you're a comedy filmmaker?"

Rebuilding film language

The work that must still be done to achieve true diversity in cinema goes far beyond representation on screen, and even representation in authorship. To begin to truly even the playing field would mean dismantling the very foundation of film language.

"Any time a person of color makes a movie it's an act of revisionism and reversal because Hollywood was absolutely forged in stereotypes," said Clark.

"From Birth of a Nation in 1915, which had full presidential endorsement, that set a very direct path particularly for representation of African-American characters, and those stereotypes have been embedded into an extraordinary amount of visual material, and it's still a fight to undo those and create new visual languages for people of color."

Bugbee pointed out the ways in which artists, especially musicians (like Jay-Z in 4:44), have been turning this language on its head. "There is a whole language built on top of not just undoing those stereotypes, but trying to dissect what they were trying to say, and how you relate to them as a person who exists after their inception. And oddly, it's been some of the most creatively rich territory."

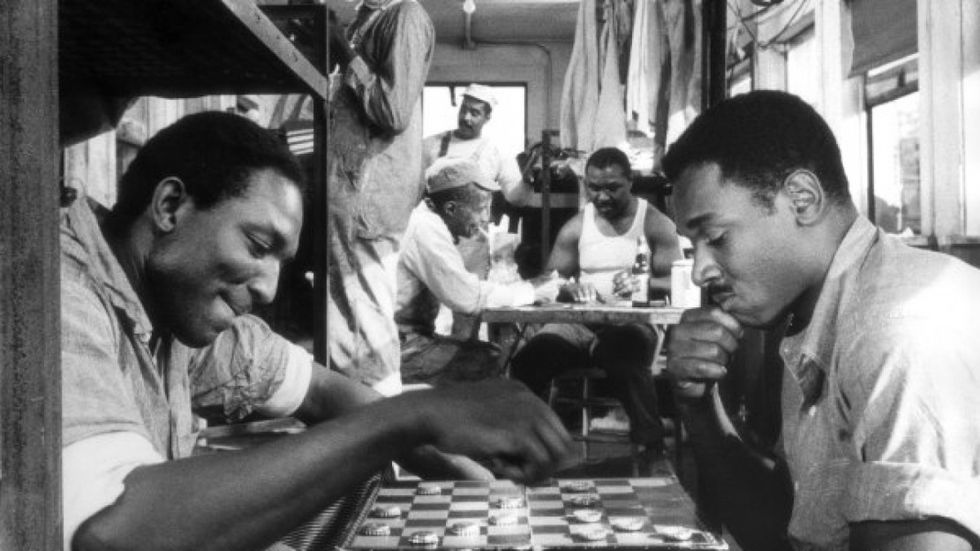

Featured image: 'Mudbound'. Credit: Netflix.