Watch: How Hitchcock's 'Vertigo' Has Influenced Cinema

Explore the incredible impact Hitchcock's "Vertigo" had on the art of filmmaking.

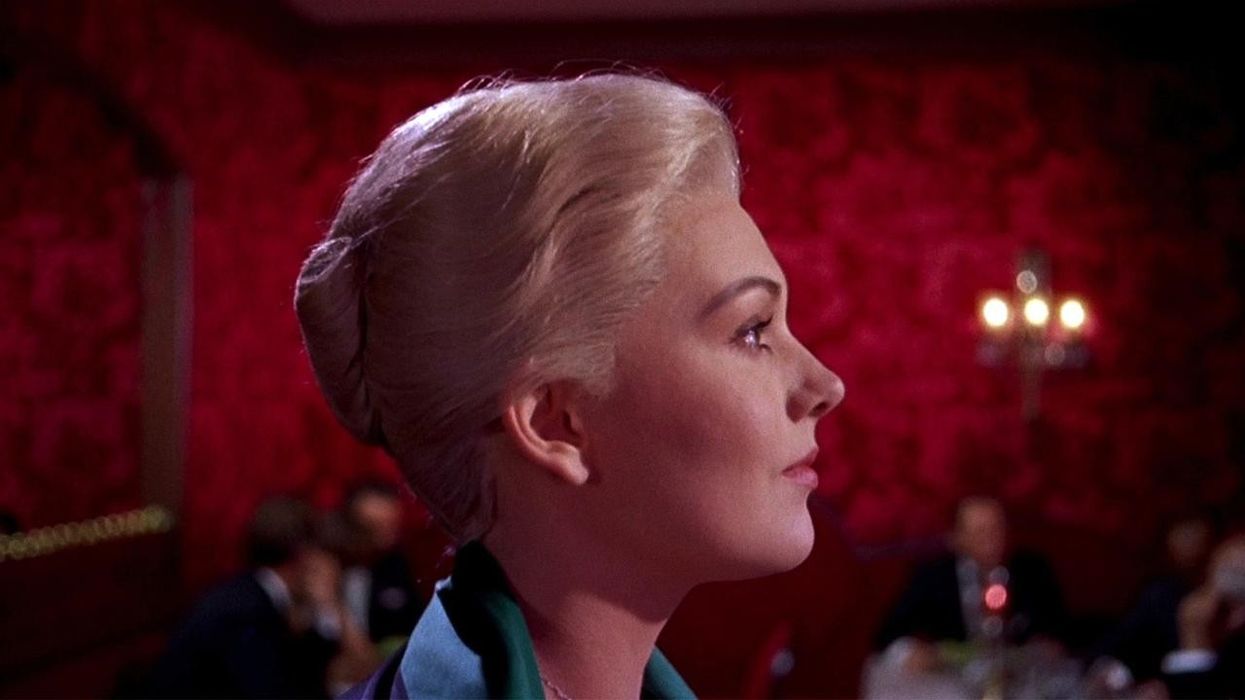

Alfred Hitchcock has perhaps one of the most renowned filmographies in cinematic history, but the film that is often dubbed his masterpiece, as well as the greatest film of all time, is his 1958 psycho-thriller Vertigo. But in its day, it wasn't considered to be anything special; with what some critics called a "slow and boring" first half, the film broke even at the box office and earned significantly less than his other works. Even Hitchcock himself had doubts about the film, believing the lead roles, which went to James Steward and Kim Novak, were miscast, and in a possible act of defiance against the film, secured its rights and essentially banned audiences from ever seeing it, a decision that was eventually reversed after his death in 1980.

Despite its lackluster release and removal from the public eye, Vertigo roared back with its re-release in 1983 and not only went on to be named Hitchcock's masterpiece by the cinematic community but also assumed the throne at the top of BFI's list of "Greatest Films of All Time", which had been occupied by Orson Welles' Citizen Kane for 50 years. But what makes Hitchcock's comeback kid such an essential film? Perhaps the answer lies in all of the films that have come after it, the films that were able to pass through creative doors that the legendary director had unlocked using his unique style of filmmaking. In this video essay, Fandor's Jacob T. Swinney explores the massive influence Vertigo has had on cinema, from the birth of the New Hollywood (American New Wave) film movement to the stylistic choices of some of our greatest contemporary filmmakers.

Though Hitchcock wasn't the first to use elements like color, composition, and camera movement to aid in telling visual stories, he did use them when Classic Hollywood Cinema reigned supreme, a regimented style of filmmaking from the 20s-60s that, yes, produced many great films, but also took fewer risks both financially and artistically. Hitchcock was one of the several directors during that time that fought the studios to keep creative control of his pictures, and once he had it, his films stood out among the others that had one too many studio cooks in the kitchen.

Vertigo came out during a time of transition in American cinema, from Classic Hollywood to New Hollywood, and it was one of the films leading the way toward more expressive visual cinematic language, much like the German Expressionist films of the 1920s (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Nosferatu, Metropolis) and the Film Noir titles of the 1940s (Double Indemnity, The Maltese Falcon, The Big Sleep). However, unlike those films, Hitchcock's style couldn't be easily classified or packed inside a genre or film movement. It was poetry, it was pure cinema, and it was entirely Hitchcock.

As you can see clearly in Vertigo, the camera is an extension of Hitchcock himself, the way he views the world and the people in it. It fetishizes, it expresses, it focuses on its interests in the same way a human would, which wasn't common at the time. That is perhaps the most striking aspect of Vertigo, not the plot, not the dialogue, but something that may seem almost natural today, but was remarkably novel and innovative in 1958: the fact that Hitchcock managed to possess the camera with who he was as an artist.

Source: Fandor