'The Yellow Birds': DP Daniel Landin on Creating Contrasting Visuals for Iraqi Desert and Virginia Mountains

'The Yellow Birds' takes an honest but also visually striking look at the Iraq War and its aftermath.

While many films that could be called "war films" depend on loudness—in imagery, dialogue, and action—to get their ideas across, The Yellow Birds is not one of those films. Based on Kevin Powers' novel of the same name, Alexandre Moors' debut feature grapples with the Iraq war, PTSD, romantic attraction, dishonesty, and fragile masculinity, among other subjects, and yet it maintains an even keel throughout, moving us through without ever seeming too frantic, even when its characters are in the midst of battle.

Tye Sheridan, Alden Ehrenreich, Toni Colette, Jennifer Aniston and many others give mature performances here, as individuals wrestling with vast problems. The story hinges on the disappearance of an earnest young soldier, Murph (Sheridan) and his close comrade's (Ehrenreich) knowledge of that disappearance, as well as the fallout with the soldiers' respective families. Despite its intricate storyline, one gets the sense that the loss here is meant to be more existential.

This effect is due, in large part, to the careful work of DP Daniel Landin, whose images are both striking and reflective at the same time, a difficult balance to achieve. He manages to find the poetic quality in both the palm-laden terrain of Iraq and the shadows of a small town in the South—and the film's characters move and grow inside this attentively portrayed world. Landin has been the DP on films such as Under the Skin and The Uninvited, as well as music videos by Lana Del Rey, Radiohead, and Bjork. NFS recently contacted Landin to discuss how he translated the thorny subject matter of this film into visual language.

No Film School: How was your development process for the Iraq scenes different than the process for the US scenes?

Daniel Landin: The heat of the Middle East was embodied by the oranges, reds and umbers of the Moroccan locations. By contrast, the milky skies of Virginia (filmed in Atlanta) enhanced the cooler spectrum. This was something we knew gave us an advantage in all the cross-cutting between the countries, which was particularly important given that (for cast reasons) we had to shoot a number of the US scenes while we were in Morocco. We particularly made use of dust and backlight in the creation of the army camp in Iraq, searching for two weeks before we found a suitable walled area that had its back south-facing and featured the Atlas Mountains, close enough that they were visible beyond the perimeter. The camera was generally controlled in times of monotonous waiting, but hand-held and fractured in the combat scenes, where we had to maximize all of our resources.

"I like to build a film with a director from the script upwards."

NFS: Many key shots in the film show characters at a considerable distance. I’m thinking specifically of the shot of Murph’s mother (Maureen) when she gets the letter saying her son is missing, the shot of Murph’s love interest (Jenny) in the camp shortly before she dies, and the shot of the car the soldiers shoot at in Iraq, killing the driver. What would you say you’re using the depth of these shots to communicate?

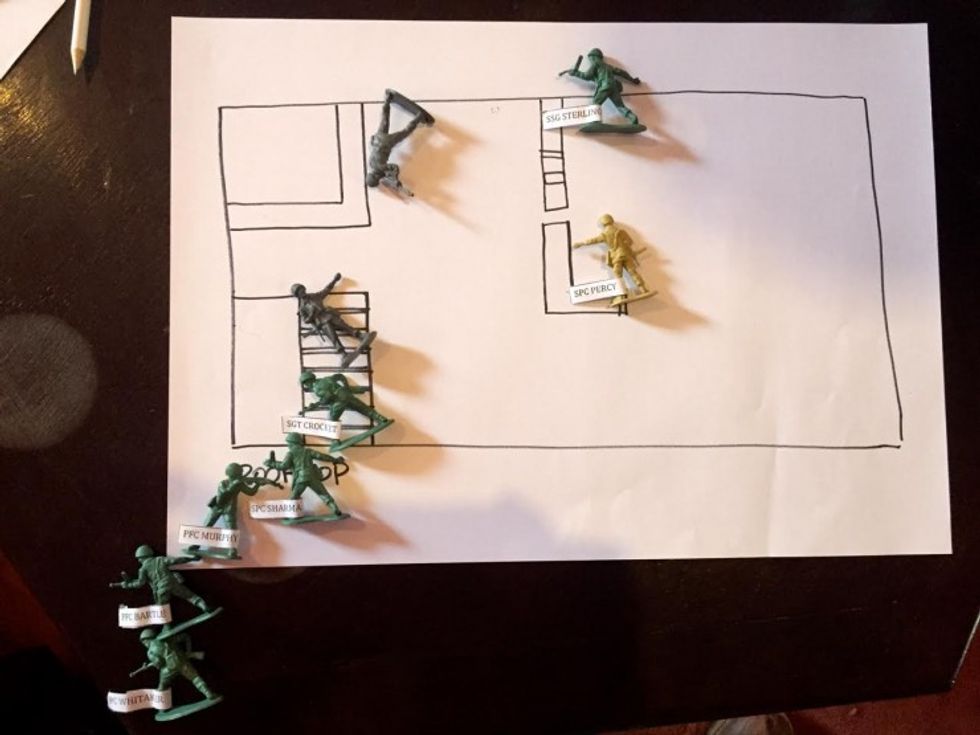

Landin: I strongly believe that there is a direct correlation between lens choices and human vision, by which I mean that although the human eye is of a fixed focal length, we are continually adjusting the subjective magnification that the intensity of experience dictates—the brain literally zooms in. When we are on the rooftop and the civilians are killed, it is important that we remain in the subjective, experiencing it from Bartle’s point of view. We get in close but from an immense distance, as if his senses are heightened by the adrenaline and pressure—this slaughter makes a great impact on him and tells us about how his war changes him.

Likewise, the distance marking out the tragic figure of Jenny is part of Murph’s alienation and her perceived un-obtainability. We are with her but will never be with her. We talked for some length about Maureen’s frame as the letter hits home, and Alexandre and I agreed we wanted to stay wide and distant, resisting the exploitative close-up and leaving her vulnerable in the suburban cul-de-sac.

Landin: In the opening party, the looseness of the camera as it tracks through the platoon with Bartle underlines Murph’s static position, as his shyness prevents him from acting—we are getting to know Murph and his naïveté. The camera remains with him and Bartle, glimpsing the relaxed and spontaneous partying of Jenny and others. Her easy confidence is only experienced from a distance.

This set up Murph’s inexperience and vulnerability and was designed to contrast sharply with the final fabricated flashback to the same party that we see at the end of the film, where Bartle seizes the moment after his horrific confession, and describes a wishful scenario to give Maureen some glimmer of light. In this fictitious idealized version of the evening, where the lights throb and the shots become giddy and expressive, he is freed, and so is the camera.

"Although the human eye is of a fixed focal length, we are continually adjusting the subjective magnification that the intensity of experience dictates."

NFS: Was your work with the director fairly collaborative, or did you have free reign to develop the cinematography as you saw fit?

Landin: As a cinematographer, one's first contact with a project is usually a script, generally unembroidered with visual clues. Alexandre and I first met on Skype, and it was only then that we began to establish if we had a visual connection, which we ascertained fairly quickly when we both brought up Klimov’s Come and See as a fundamental reference point. I like to build a film with a director from the script upwards. The choices of light and lenses derive from the content and must always be driven by that.

Once we started pre-production in Marrakesh, we all would meet for script read-throughs to understand and contribute to our director’s film. Alexandre’s background is graffiti and graphics; he can generate rough storyboards and visualizations very spontaneously, so we could move very quickly in our collaborative understanding of how to shoot a scene.

NFS: I'm always curious about how cinematographers go from the script to the image. Could you give an example of a point in the script where nothing was necessarily readily evident or calling out to you in the dialogue itself and you had to extrapolate, to sort of "solve a puzzle" to film the page?

Landin: One puzzle that we had to solve was the movement from night to dawn, as the platoon advances across the pomegranate orchard. We decided that the best way was to have a separate wordless scene as the soldiers walk out into the half-light, past the burnt trees that have been devastated by the previous night’s firepower. We shot this in a brief window of dusk, tacked on to the schedule, and the eerie gloom created its own meditative quality that served to reflect the disillusionment that we’d seen when Bartle is interviewed by the reporter, and acts as a precursor to his disoriented standing-up sleeping before the firefight.

Landin: As I said earlier, the tone of Come and See was a crucial reference, not for the battle scenes, but for the accelerated journey out of childhood, the naive lust for action followed by the embittering of the spirit, and above all for the corruption that follows the false sophistication of combat. Alexandre had a strong desire to consider the transitions between scenes to traverse the various time slips that occur throughout the film, and together we watched Bad Timing (Nicolas Roeg) and Wages of Fear (H.G. Clouzot). These considerations paid off well, and during the DI process we were able to align dissolves and cuts in an attempt to echo the poetic juxtapositions of the original novel. Other films we watched were Beau Travail by Claire Denis, Battle for Algiers (of course!), Kurosawa’s Dersu Uzala and a lot of surprisingly candid US Army postings on YouTube.