6 Tips From Paul Schrader on How to Turn Personal Agony into Award-Winning Scripts

Are you talking to him? Because he's talking to you.

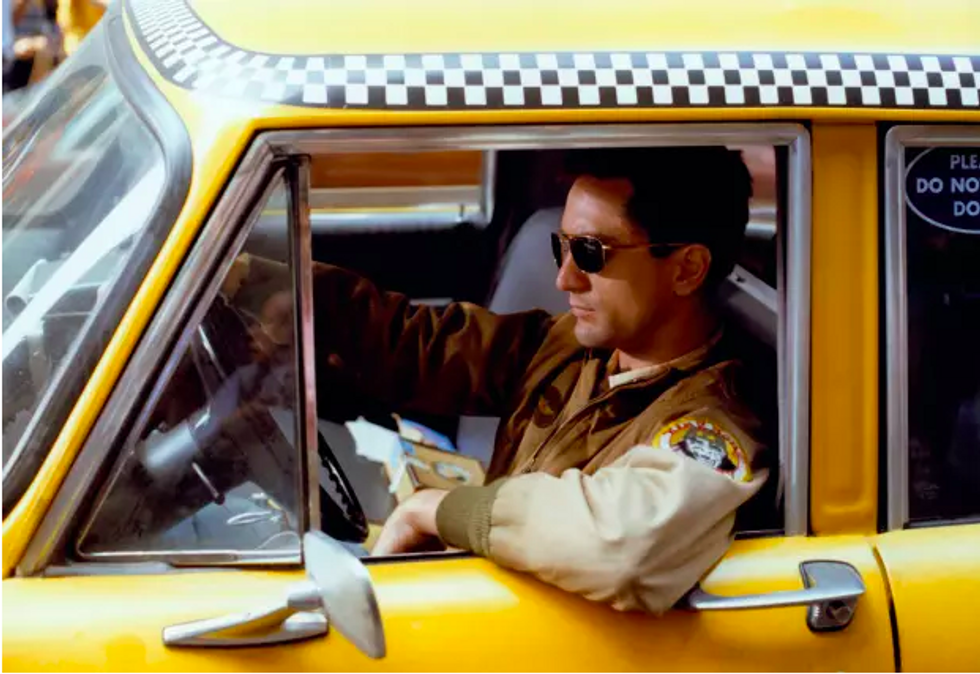

Legendary screenwriter, director, and film critic Paul Schrader has penned some cinematic classics, most famously Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976). The collaboration went so well that Scorsese called his scribe back for three more films: Raging Bull (1980), The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), and Bringing Out the Dead (1999). In addition—no small achievement!—he is a director in his own right.

In between writing scripts, Schrader has helmed 18 feature films including Light Sleeper (1992), Affliction (1997), and just this past year, the critically acclaimed drama First Reformed (2018). He’s known for engaging stories, masterful pacing, and palpably tortured characters.

Staring at a blank page? Perhaps you’re a future Paul Schrader—or at least a future screenwriter resorting to No Film School as a great way to procrastinate. No worries, we’re here to help: NFS was lucky enough to hear Schrader dish wisdom at the 2018 New York Film Festival. Here’s Screenwriting 101 from this singular wordsmith.

1. Turn screenwriting into personal therapy

Paul Schrader got his start as a film journalist and critic, reviewing movies for local publications in Los Angeles. He graduated to writing seminal books and essays on film theory, including Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer and Notes on Film Noir. He wasn’t satisfied by mere intellectualization. He had the urge to tell his own stories.

If you’ve seen even one of the films within Schrader’s impressive oeuvre, you may recognize his favorite themes: characters on a path of self-destruction, lost souls who’ve been offered a chance at redemption, damnation, or both. With film titles like Obsession and Affliction under his belt, you can imagine that Schrader harbors his own darkness.

Hearing him speak, however, suggests the opposite story: he comes off as a generous-spirited mentor. Who’s to say what’s going on inside? Screenwriting, Schrader revealed, has been the best way for him to exorcize demons.

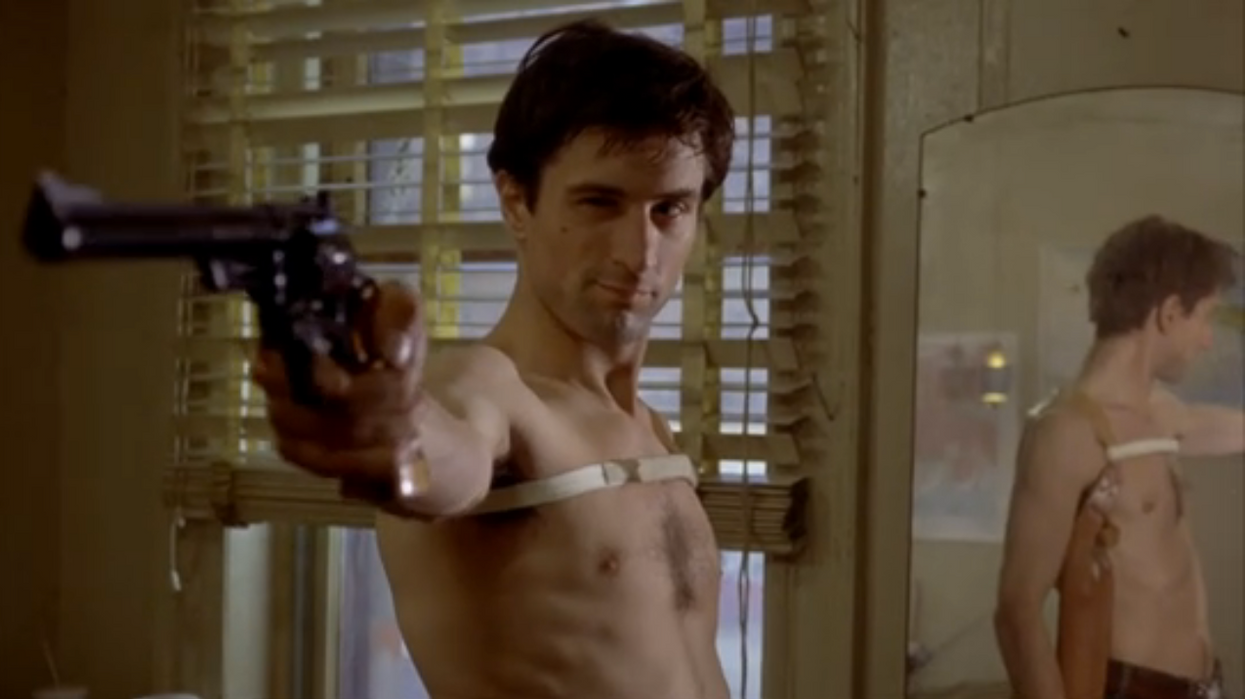

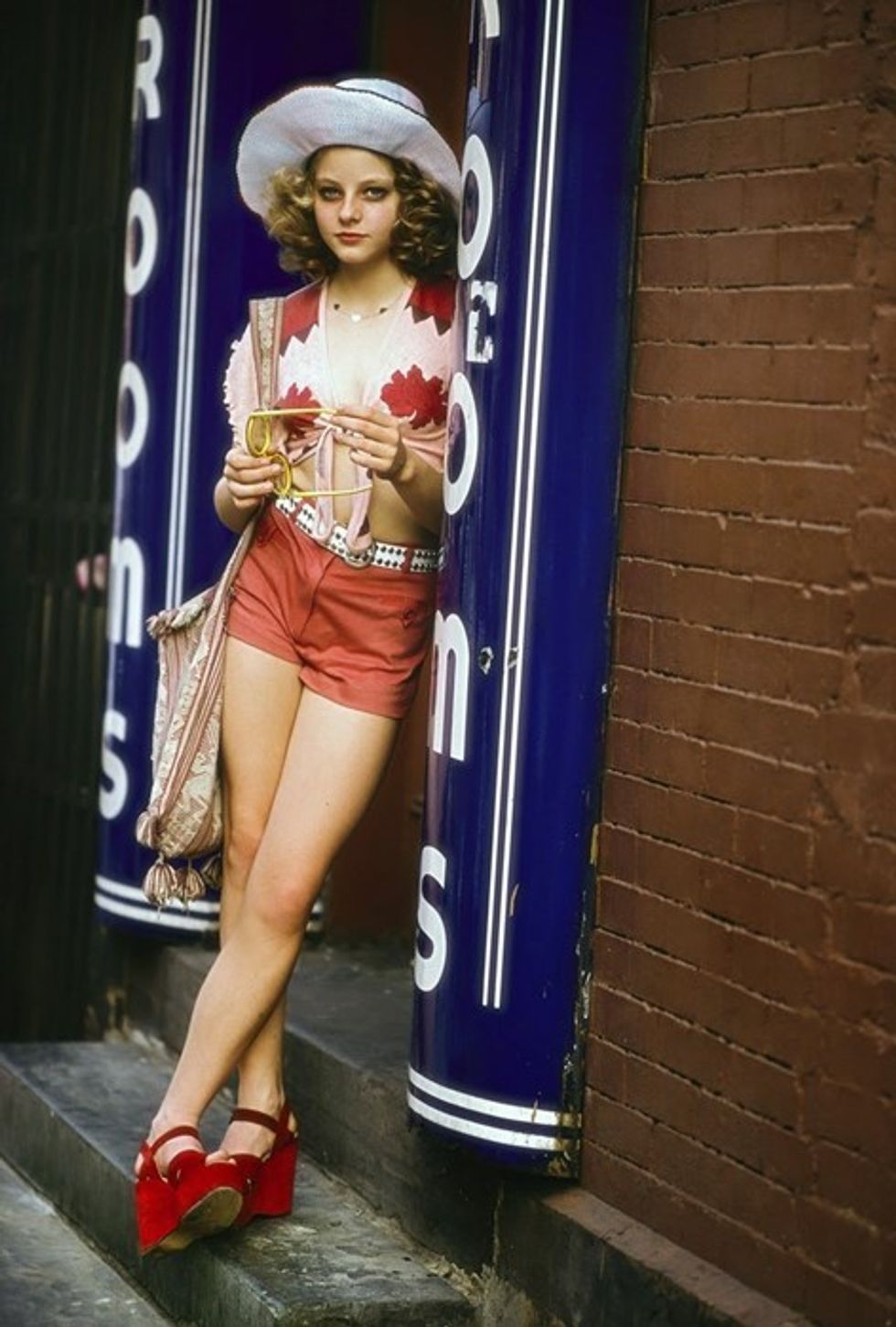

“Many people see screenwriting—incorrectly—as a conduit to fame and success,” He shook his head, rueful, "but screenwriting has a practical application that you can use in your life: introspection. I wrote Taxi Driver as personal therapy for some dark things I was going through at the time. Every time I write a script, that’s still the door I walk through.”

Schrader has turned catharsis into a dual career. As it happens, the erudite writer doubles as a screenwriting professor. He admits that his method may not be for everyone, but encourages you to try it—and to start simple. Here’s what he tells his students: “Isolate a problem in your life. Then come up with a metaphor for that problem. Then start writing through that metaphor and see what happens. For Taxi Driver, I was lonely, the metaphor was driving a taxi cab through the city, and the plot gradually found me.”

Schrader doesn’t let his students start writing until five weeks into their course. “The first four weeks is group therapy,” Schrader admitted with a gravelly chuckle.

2. Outline your story beats

As Schrader tells it, four weeks may not be enough for gestation of an effective screenplay. Schrader mulls over an idea for months (even years) until he knows it inside and out. “I don’t like to start writing till it feels right, till I feel ready,” the screenwriter explained.

Even then, it’s a step-by-step process. Schrader swears by the act of outlining a project—listing all the beats of the entire story on a single legal pad—before even attempting page one. He tilted his head, ruminating: “If something’s missing, you can just feel it.”

3. Test your story on friends

OK, so you’ve got an outline—but you’re still not ready to write your script. “Screenwriting is not really about writing, it’s about telling,” Schrader asserted, "and that takes practice.”

Remember that legal pad filled with notes? Schrader uses it to make oral presentations. “Buy a friend lunch or coffee and tell them your story in its entirety. It’s like stand-up. If you’re losing your audience, you invent new stuff—and then you have to write it in. When you get to a point where you can tell your movie’s plot for 45 minutes without losing their attention, then it’s time to start writing.”

As Schrader relayed the details of his rigorous process, it was clear he wasn’t embellishing. In fact, he advises the same rigor for all screenwriting: “By the time I write page one, I have already outlined my story AND told it orally, so I know all the beats by heart.” Then, finally, he writes his script in a couple of weeks.

4. Build a framework

His writing process is equally rigorous. “I write from 10pm to 5am. Actually, I drink my way to 5,” Schrader smiled, almost sheepish. (First Reformed, his latest, is about alcoholism), but I have a friend who wakes up at 6 am, smokes a joint, and writes, and he’s a perfectly good writer too.”

Needless to say, you don’t need mind-altering substances to write a screenplay (and No Film School does not encourage or condone this type of behavior!), but you DO need to take time to find your process. This is where Schrader advocates deviation from his own strategy: “I know other writers who can figure out the script as they go, through trial and error. You have to find out what works for you.”

But for the 72-year old Schrader, his chosen approach has proven the most productive. He also warns against overwriting: a mistake often made when screenwriters are floundering, or, to put it more kindly, searching for solutions.

“For me, the main script rewrite happens in rehearsal, when you’re finally hearing people say the words,” Schrader explained. As preparation, he recommends going in with a short first draft—only as long as the story needs to be. “But don’t cut your script down,” he warned. “Cutting is thinking reductively.” Instead, he suggested, “Start small and think ‘adding!’ not subtracting. I have the same approach for editing. If the first draft is 60 pages, that’s good. If your script works in half-an-hour, it’ll be even better as a one-hour.”

Schrader’s argument is convincing. After all, he has learned from experience: once a script has been outlined and tested, once action and emotion has hit all the right beats, you have a framework for your dialogue as it evolves...and the making of a powerful narrative.

5. Write to sell...then disappear

Schrader also vouches for the age-old maxim of seducing the reader in the first few pages. “You should write as if you want to sell to someone else,” he insisted. “Imagine a production exec reading a bunch of scripts every day—they’re just looking for an excuse to put each script aside. Try to make it accessible.” He paused, then laughed: “And to do that, sometimes you have to whack yourself in the head with a two-by-four and ask yourself, ‘What am I doing?’”

After that, your job is over. Schrader believes in setting boundaries: “No writer should insert directorial or editorial commentary into a script,” he asserted, "and no writer should be allowed on set.” This advice comes from a writer/director! Clearly, Schrader knows how to compartmentalize roles, but even so, he is careful to reiterate that his approach may not be ideal for everyone.

6. Find common ground

So then how do YOU find your own screenwriting method? What’s the process behind the process?

The final insight from Schrader was about developing characters in a script—and how his background in journalism helped prepare him for a career based on understanding motivation. What drives a character’s actions? What lies under their surface persona?

“Journalism, and specifically the act of interviewing people, was invaluable for teaching me to read people,” Schrader reasoned, adding that this technique is possible even for those who are not journalists. “We’re all human,” he explained, "no matter who you are, if we talk, I’ll find common ground. That’s how you should think as a writer.”

As Schrader would have it, it all comes back to empathy. Most important is tapping into that inner-resource, that deep well of humanity where your ability to feel others’ pain—and joy—will shape your own thoughts and feelings. That’s why screenwriting is so akin to therapy: once you become a storyteller, you’ll be spending your time exploring your deepest self—and one way or another, life has a tendency to bleed into work..and vice-versa. Out of this, great scripts are born.