Editors note: The following is a guide put together by director Zeek Earl and Production Designer Matt Acosta. Their film Prospect hits theaters everywhere this Friday, tickets can be found at www.prospectthefilm.com.

Prospect was conceived with the desire to create an original sci-fi universe with a level of immersion that defined the classic sci-fi films we grew up on. Blade Runner, Alien, and the original Star Wars movies featured deeply rendered worlds that felt alive, sparked the imagination, and left you wondering what else exists in back alleys and corners.

They were tactile, rendered in actual physical objects - the props, costumes, and sets. The challenge for us was how to achieve this feeling on an indie budget. This is by no means a template for how to do production design for any movie, but rather a breakdown of our unconventional approach, from which you might find a few ideas you can steal for your project.

WRITING TO A BUDGET

In the indie space, you need to be conscientious of scope from the very beginning. While writing, we tried to be aware of the production implications of everything - the difference between someone getting shot in the head versus getting shot in the arm, for example. We were lucky to have our core production design team involved throughout the entire writing process. Individual sets, locations, costumes, and props were debated before their scenes were even written, so we didn’t get attached to ideas we couldn’t afford. Budgets were made early on and constantly revised. By the time we actually went into pre-production the script was already heavily vetted to be realistic to the resources, we were asking for, helping us avoid painful creative cuts.

SPENDING MONEY CREATIVELY

Half the creativity in indie production design is how you spend your money. Prospect had a production design budget of $840k. That’s not small in the realm of indie film, but that’s a minuscule amount to any Hollywood line producer trying to build a Star-Wars-esque world. The way we pulled it off was by setting up our own production design shop. We rented a retired shipbuilding warehouse sandwiched behind a weed shop and an Episcopal bookstore on a one year lease and immediately started scanning craigslist for used tools.

We chose to invest in labor over materials. Smart people can make incredible things out of cheap materials. We also did our own research to question even expert-sounding opinions. There is never one way to do anything and it’s always worth seeing if there’s a cheaper alternative even when you are talking to a confident source.

Creating things originally may seem more expensive than ‘off the shelf’ options, but non-original designs have implications you may not be thinking of. We thought for example, that a lot of vintage electronics could be plugged straight into our spaceship designs with just a quick paint job. However, the time and effort to accommodate those non-custom pieces was often greater than starting from scratch and also had the disadvantage of not always feeling cohesive to our world.

The techniques we used to set up the Prospect shop were learned over years of doing short films and commercials at much smaller budgets. The short film that we used to get Prospect funded had a production design budget of $9k (and a lot of donated labor). Our pitch to investors was that we would make the feature with the same techniques. We had also rented a warehouse for a month to make a bunch of Wes Anderson inspired web commercials for Microsoft - again just hiring our friends - because it was more fun, gave us complete creative control, and was the only way to do it in the budget space. The trade off: a lot more work and unpaid overtime and weekends.

DIY MENTALITY

The majority of our production design crew had never made a feature film before. We hired a bike builder, a remodeling carpenter, a recent industrial design grad, a motorcycle mechanic, a bunch of cosplayers, a camera assistant who wanted to learn mold making and passionate friends with no relevant resume. But everyone was ambitious and proved their ability in unconventional ways. Looking at a custom bike frame can give you a sense of someone’s ability to make a spaceship. They were willing to join this scrappy thrill ride for the experience and the opportunity to create something unusual. And most important of all, they were willing to put in hundreds of extra hours to figure out how to do it.

There was also a lot of above and beyond personal investment put into the production design. It’s naturally more fun to build spaceships, but there is a powerful sense of comradery that forms when a group of people are gathered together for a singular objective. Individual members were often given ownership of certain elements and they would end up volunteering extra time to make their element the best it could be.

YouTube videos from Adam Savage’s shop were constantly playing. We learned Rhino 3D, got a crash course in molding and casting, we built a cheap CNC from a kit, took some Stan Winston online courses, and learned when 3D printing is cost effective and when it’s not. Within the shop people who came in with a certain skill would often host a mini-workshop to teach it to others.

One of the things we underestimated was project management. When you go the DIY route, you have to compensate for all the middle-men that keep things running smoothly. Management is the key to being able to quickly make priorities and ensure stuff gets done. We were constantly needing to revise budgets or take people off one project and put them onto another as things evolved. We came in on budget and on schedule which does not happen without constant planning. In our case, not hiring more managers resulted in people getting managerial responsibilities added on top of what they were already doing - which worked out ok - but meant lots of overtime and long hours that wouldn’t be sustainable over the course of a career.

DEFINING THE AESTHETIC

Before pre-production began we created an encyclopedia of the Prospect universe that explored the world well beyond the boundaries of the film itself. It defined even minor characters’ backstories, home planets, and economic situations. No matter what department someone was working in they had a clear context to where their piece fit.

Concurrently, we also created a production design bible for design-specific reference. It outlined all the important aesthetic tenets and rules for our world: the color palette, the materials we allowed, the materials we didn’t allow, the preferred geometry, and the design dos and don’ts. For example, when designing a background spaceship interface, lean on the geometry of vintage Teac or Korg but never iPod. The bible also extensively cataloged our inspirations. One of the techniques to making designs feel original is to have so many inspirations that you’re stealing just a tiny piece from each one, and through the fusion, you end up in a place that feels entirely new.

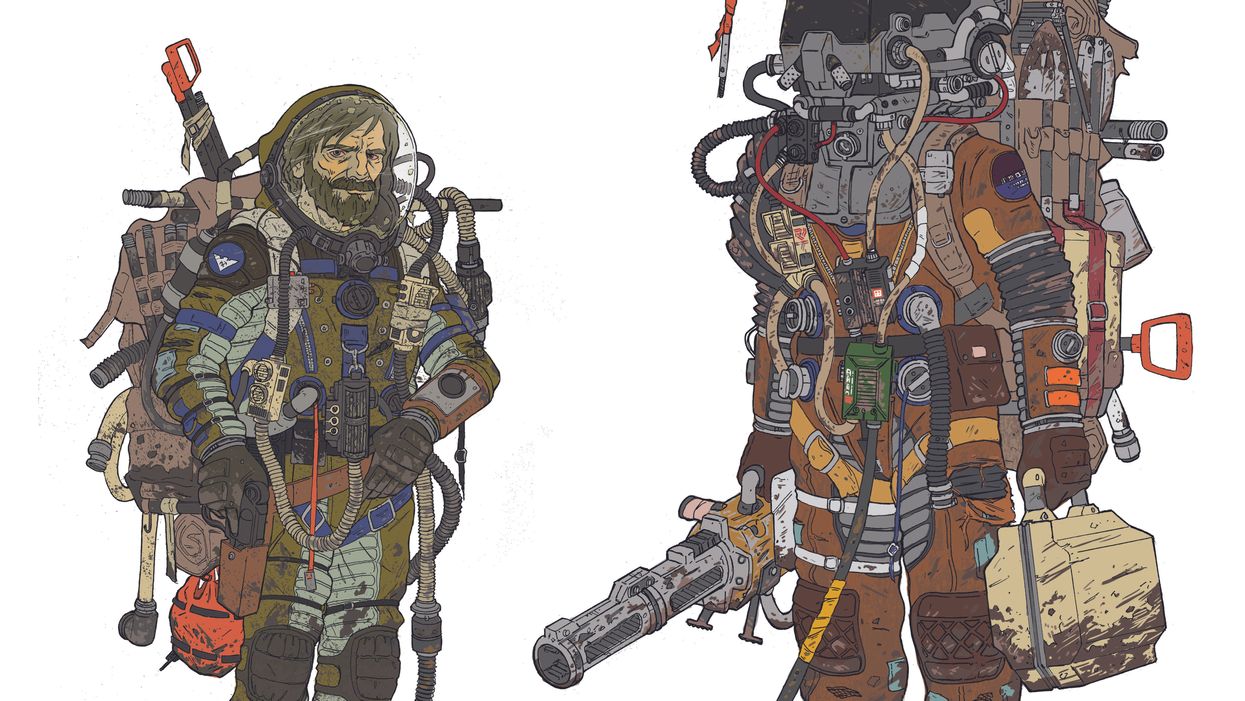

The bible was used in conjunction with detailed concept art. Often concept art is more impressionistic, but in our case, we chose to create highly specific renderings of each character that could be passed around to different departments and ensure continuity. The art itself almost became a blueprint and was always a useful touchstone even when we diverged from it.

RELISHING THE DETAILS

Production design is world building. When establishing a believable and compelling world the small pieces are just as important as the big ones. A spacecraft owner’s manual, flipped through briefly at the start of a launch procedure, can set the tone for a scene as much as the spaceship itself.

A few weeks into pre-production, we realized graphic design was going to be a much larger task than we anticipated. It’s the minutiae - the everyday details like garbage, scribbled notes, gum packaging, and an original language (with calligraphic, typed, and handwritten versions) - that contributes so much to the world building in the film, making facets of the universe visually self-evident and helping to keep exposition out of the mouths of the characters. We had to put together a team of designers on the fly. We emailed a lot of past commercial collaborators and asked if they would do a piece for our crazy sci-fi movie and a few interns from our alma mater jumped on the opportunity to distinctively expand their resumes.

When it came to detail, our approach was to overcompensate. We didn’t worry solely about what was guaranteed to end up on the screen; rather, we wanted to go through a thorough process of thinking through everything that made sense in an environment. This resulted in a lot of pieces painfully not making the final cut, but it opened up new possibilities and allowed us to point the camera anywhere and give our actors a complete setting to work in.

When designing our hero props, our production designer Matt Acosta would ask, "Does it pass the Jurassic Park Barbasol-DNA canister test?" Which meant, is it individually compelling and does it tell a story on its own? It was important that these details not only perform their function within the story but also suggest something of the greater universe outside the film. A good example is our main character’s rifle which was designed to roll up so it could flat pack for cramped space travel. On screen, this detail wasn’t explained and lasted only split second, but in that moment it set off alarm bells in the brain and inspires the audience to think about or imagine the rest of the Prospect universe without skipping a beat.

THINGS BREAK

On set things worked out very differently to how they were planned in the shop. It was essential to be prepared for all variables and flexible enough to handle it when things go wrong. We tried to test everything in realistic conditions, like putting our space helmets in the shower to see how they would hold up in the rain.

It was also necessary to make duplicates and stunt versions. If you find yourself being delicate with a prop in the shop, remember actors trying to make it look real will not be. One of our favorite scenes involved Pedro Pascal grabbing a rifle and throwing it into the wall of a spaceship. It was improvised and definitely broke the rifle, but thankfully we had a second one to use while the first was repaired.

We adopted an attitude of pessimism around objects’ durability which served us well. We had hundreds, literally, hundreds, of props, both major and minor, break while on set. In our case, we got lucky that several of the shop members signed on to be PAs on the actual shoot and were available to help fix things as we went.

Despite the extreme workload, being able to make this film with our unconventional family of artists was the most thrilling and fun creative environment we’ve ever been in. There is no one way to make a movie and we stumbled and succeeded in equal measure. I hope there’s something helpful to learn from our experience.

Featured image at top: "Ezra and Number Two" — concept art by Laurie Greasley