Why 'Texas Chain Saw Massacre' Has One of the Best Openings in Horror

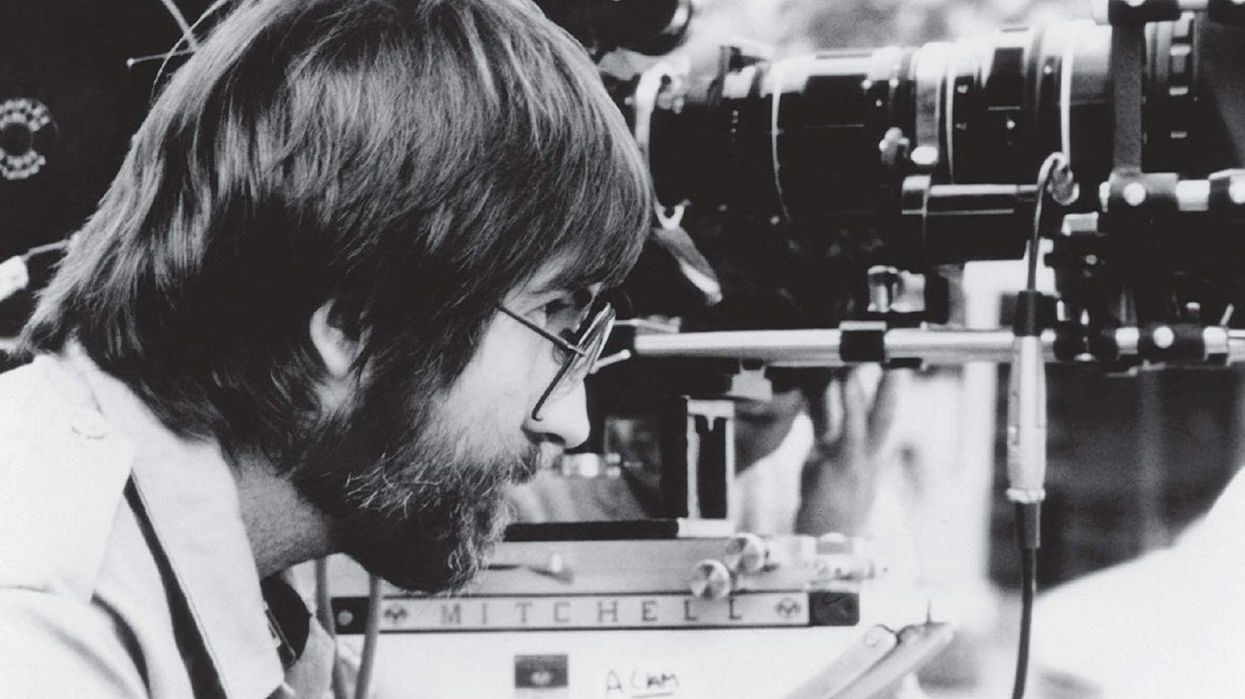

A new book explores the work of masterful horror writer/director Tobe Hooper.

You know the work of Tobe Hooper.

Even if you've never personally watched Leatherface wreak havoc upon a group of unwitting young people passing through rural Texas, you have witnessed Hooper's contributions to the horror genre, slashers, and gore effects in all the movies that came after The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.

The film is one of my favorite works of horror. It was one of the first films I watched that made me feel the bleakness and fear of the situation the characters were in, but also made me realize the potential for color and light in horror. It's so gosh-darn beautiful, and sunny for almost the entire runtime. It's a gorgeously shot film, which only adds to the discomfort of watching the violence unfold onscreen.

If there's anything else I love, it's a niche film book, especially ones about horror as a genre or my favorite horror filmmakers. One I enjoyed recently is American Twilight: The Cinema of Tobe Hooper, which delves into the filmmaker as well as the context of his films.

Horror as a genre is a rich playing field that often allows writers and directors to address societal turmoil and personal fears. In American Twilight, Hooper is given the attention he deserves as a contributor to the canon of horror as a genre for his exploration of an "America in crisis." His monsters often were shown as terrors trespassing on the nuclear family and domestic bliss.

The book addresses his major works like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Poltergeist as well as lesser-known films like Spontaneous Combustion and The Mangler, and how he uses these scary tales to explore masculinity, sex, aging, suburbia, and more.

There's an essay near the end by J. Shea and Ned Schantz that examines the opening sequence of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and how it so effectively lurse the audience into the story. Let's check out the takeaways.

The best horror opening

The opening of this story is a series of images and conversations that all work fully to support the movie's tone and theme. It begins with a false claim of being a true story. It's ominous in its warning of what "you are about to see."

The film then begins with a grave robbery and the desecration of a corpse, posed atop a headstone, while a corresponding radio report of the event plays. And, as Shea and Schantz point out, it's hot in this shot. The sun is blazing. Dust blows across the cemetery. This heat and brightness are established from the opening image and create a sense of discomfort immediately.

The young characters pass a feedlot and slaughterhouse. They discuss how the cattle held there will soon be killed. The writers point out here that the characters are mirror images of the cattle being prepared for slaughter—trapped in their hot van, shown in tight camerawork, smelling death nearby.

This is all fitting, it turns out. The essay refers to a 2014 quote from Hooper about the bovine inspiration for the film (via Interview Magazine):

"I had an experience in a restaurant one time where there was a large trolley with beef being carved up, and I just transposed different images onto it. Like, what if there was a nice little cow there with a bowtie and a knife carving up humans. I was a vegetarian for a couple of years after that."

Sally (the film's final girl) then spots a hitchhiker, whom they pick up because of the heat. Appropriate, as the writers point out, because she'll be a desperate hitchhiker herself soon.

Hooper chooses to hide the identity of this character for several shots. We see the young characters react to him. Franklin calls him "Dracula." That makes his reveal a few moments later (stringy hair, sweaty, jerky movements) all the more impactful.

The discussion turns to the slaughterhouse again, in particular a graphic and enthusiastic conversation about "headcheese." The scene becomes a dance of social mores, hospitality, and expectations—the others are disgusted, the hitchhiker briefly abashed. He's excited by Franklin's knife, and tests it on himself, to the others' dismay. He invites them for dinner, they refuse. He takes a picture of Franklin, then demands payment for it.

It's all just a bit off, with increasing tension as the hitchhiker's behavior grows more strange.

And he does. He burns the photo and lashes out at Franklin with a knife, jumping out and smearing blood on their van. Like the armadillo, they've been injured on the road, their van potentially marking them as victims. They continue their journey into the cannibals' trap.

All of these simple elements put together create one of the most effective openings in horror history, and set the tone perfectly with thematically appropriate dialogue and cinematography.

Remember the importance of your opening scenes. How can you use imagery, dialogue, and pacing to establish your world in the first seconds of a film? How can you say more through your choice of shots and conversations to reflect what is happening thematically in your story?

And what's your favorite horror opening? Let us know in the comments.

You can read more in American Twilight: The Cinema of Tobe Hooper.