'Winning the Lottery' of a Sundance Premiere and Hulu Distribution

Liza Mandelup's feature debut, 'Jawline,' swept Sundance and nabbed a Hulu premiere. Here's how it all went down.

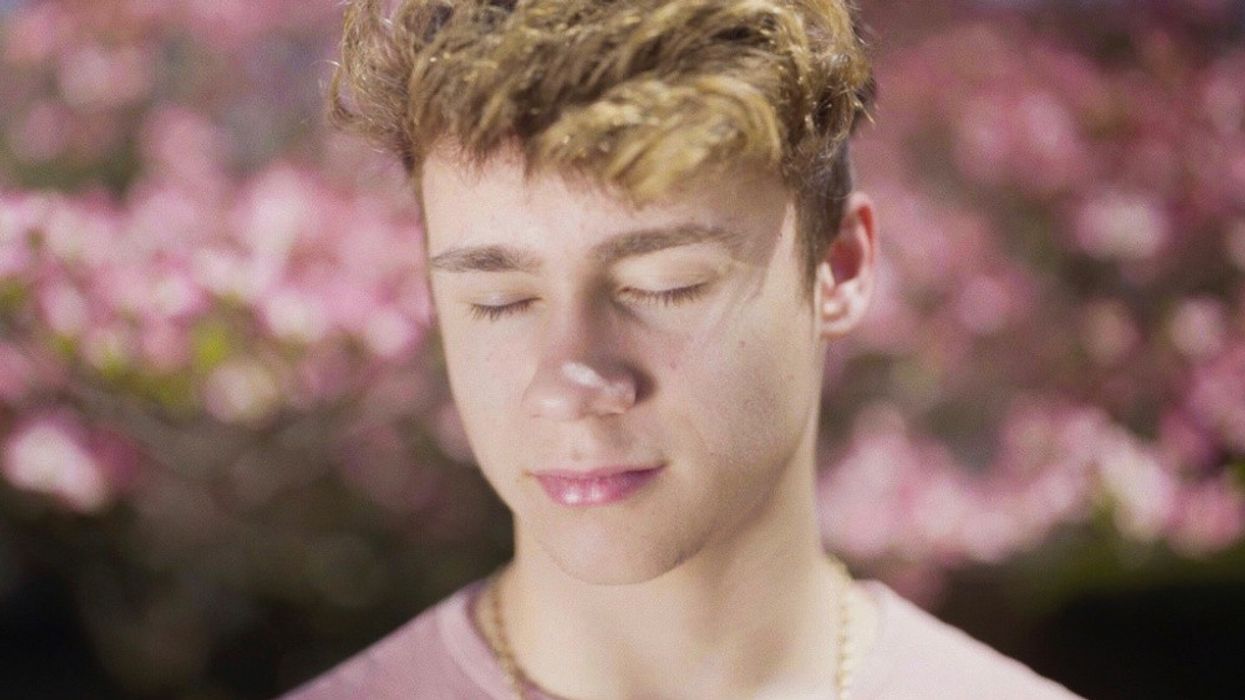

Growing up in a small, economically-struggling town in Tennessee, 16-year-old Austyn Tester didn't expect fame and fortune in his future. Then, he became a YouTube star.

Similarly, Mandelup didn't expect too much from her first feature film, about a star hopeful who was banking on his good looks and positive messaging to launch a celebrity career. Then, her film got into Sundance—and got picked up by Hulu.

Tester and Mandelup's success converge in Jawline, which follows Tester on his journey from regular high schooler to social-media star. He does this mainly from the comfort of his own room, where thousands tune into his YouNow live-streams to gain inspiration and satisfy fangirl crushes. Mandelup spent four years following Tester, filming in between gigs on commercial shoots and applying for documentary grants where possible. Jawline is an intimate, unjudgmental portrait of social-media stardom, with its lightning-quick rise and fall.

"You don't make films to think about what buyers want and what distributors want and what will sell at a festival and for how much. You make films because you have an itch you have to scratch."

No Film School sat down with Mandelup to discuss how she navigated the murky waters of the film distribution landscape at Sundance, why technology is giving modern teenagers so much anxiety, and more.

No Film School: You've made some pretty great shorts, but this is your first feature. Take me through the process of how you got this off the ground in the first place, making the jump from short to feature.

Liza Mandelup: I knew I wanted to make a film about teenagers falling in love through technology. I was tossing around all these different themes in my head. I hadn't made a feature before, but I had a lot of connections in the world of short documentary. So I first made the documentary short Fangirl, and through filming that, I was like, "There's so much here. I have to make a feature."

Filming with all these girls who were obsessing over these [online stars], I really felt I needed to know who these guys were and understand what their role is. I got more interested in telling the story through the perspective of the boy, but still from the female gaze—something that almost feels like a dream or a fantasy or even a diary entry, but it's through one of the boy's lives.

NFS: How did you find Austyn Tester, the subject you focused on ultimately for Jawline?

Mandelup: I filmed for about a year before I even met Austyn. We were kind of doing this exploration filming where we were going to different events and filming with different characters. That was a really tough time because you're spending a lot of time filming stuff and you don't necessarily know where it fits in. You don't know what will make it to the final cut. You're kind of just going off hunches: "We should follow this; there might be something there."

Mandelup: I was putting a lot of feelers out about what I wanted in a main character. I knew I wanted it to be someone who was 15 years old, someone that we could follow at the very start of their journey. I didn't want them to be famous, but I wanted them to have really high stakes in becoming famous. I a character that was going to put a lot on the line to get there. I wanted it to be someone who was removed from LA or New York, so they felt that it wasn't necessarily easy for them to get into the industry.

Someone randomly found Austyn online. He didn't have a lot of followers. We went to meet him and immediately we were like, "This is our main character." It was so instinctual because we had talked so much about what we were looking for at that point. I just knew he could carry the story.

"I tried to be careful in the beginning, because when you're first filming with someone, they don't know what they're signing up for, and you don't know what role they're going to have."

NFS: How did you get Austyn to agree to participate in the film? You have a very intimate view of his life.

Mandelup: He was so excited. I tried to be careful in the beginning, because when you're first filming with someone, they don't know what they're signing up for, and you don't know what role they're going to have, necessarily. In my head, he was the main character, but people date before they get married! I didn't want to scare him away. I never wanted to over-promise anything, because the last thing I want to do is to come into someone's life and be like, "This could change your life," or, "You're going to be a star," when I know I can necessarily deliver. I always try to be as respectful as possible [with my subjects]. I'm always thinking about their expectations and their feelings.

So we just took everything step by step. I was like, "Could we come and film with you for a little bit?" and then, when we were leaving, we were like, "We'd love to come back." And then when we were there the next time, he would be like, "Am I a big part in this film?" and we'd be like, "Yeah, you're one of the main characters so far."

I'm just all about transparency every step of the way. We went into Sundance without distribution, and so even at that stage, I never wanted to over-promise anything. Before Sundance, I was like, "We have to get into a really good festival in order for the film to be seen by a lot of people—that's what we're hoping for." I never wanted to tell him that it was going to be bigger than it was.

It's hard making a documentary where you're selling it to the distributor, so you have to get into a festival. You're working so hard, but every step of the way you just don't know the future of it. So it was kind of about looping him into what my reality was.

NFS: How long did you shoot with Austyn for? How did you manage your production calendar?

Mandelup: It took about four years to make. We met Austyn about a year in, and we would film off and on. I'd be like, "Oh, I feel like this needs to be a 10-day shoot," or, "We need to be there for a week." I played it by ear each time. Towards the end [of production], I'd be like, "I think I've got everything," and then I would go back. And that kept happening.

But it was also very loose because we had other elements going on. We were filming with [other characters] and a lot of fangirls. And then, as you get really deep into the edit, my editor would literally tell me, "We don't have a beat here," and I would be like, "Oh, I have to go back and get that. I'll go next week."

"For the first year, I was self-financing. I would go on a job and then I would go on a shoot for Jawline."

NFS: That sounds pretty flexible. Did you have to film piecemeal because of the financing as well?

Mandelup: Yeah. For the first year, I was self-financing. I would go on a job and then I would go on a shoot [for Jawline]. The amount I worked determined the amount that I could shoot. I remember I went on a two-month job once and then I came back to filming, and it was a difficult time because I had been abroad and traveling and I just hadn't kept in touch [with Austyn] as much as I should have. I realized that if you're going to commit to a project, you really do have to commit to staying connected to the people all the time.

I didn't just work on this for four years. I did a lot of shorts and branded and commercial work. I was able to balance all of that while making this film, and I think that that made it so that I didn't lose my mind. I don't think I could have just worked on this for four years alone. You have to be able to give space to things. Like sometimes, I'd film and hit a wall where I was like, "I don't really know what else I need from this moment," so I'd go into the edit and figure it out. That whole process just takes time. That's the beauty of being freelance—your whole schedule is this juggling act.

Filming the first year was pretty slow because I was just filming as I could. But then, once we linked up with Caviar, who was one of the financiers of the film, we finally had money, and so we went and shot a lot and amped up.

NFS: How did the rest of your funding come together?

Mandelup: We got the Sundance grant, and we got the SF Film Fund Grant, and then we partnered with Cinetic.

NFS: At that point, were you angling for a Sundance premiere?

Mandelup: Of course we were thinking about that. We worked so hard and then all the producers are like, "What next?" And we're like, "We don't know, get into a festival?"

By the time we were submitting to festivals, I felt like I was trying to win some sort of lottery. I thought, "Oh, I am not in control right now. This is up to someone else. I'm just going to enter this pool and if someone decides that our film is good, then we're going to get a premiere." It felt very much like I had to surrender everything at that point.

NFS: That sounds really scary, especially when you've got so many people on the line.

Mandelup: I was not chill. There was a lot of anxiety happening during that time because I cared so much. I think that's the hard part—this was a project that I had poured so much of my time and my love into. I really, desperately wanted to have a conversation with a bigger audience. And I almost felt like I might die if I don't get to have an audience at the end of all this hard work. I didn't know how I'd handle it." It felt so extreme to me.

"When we got into Sundance, I felt like, 'We're good now.' And then I was informed that this is the start of the journey."

NFS: In a way, I think that kind of extremity is necessary because it pushes you to actually finish the film, which is really hard to do.

Mandelup: Yeah, you're right. Even toward the end, there were so many times when I was so exhausted. But I needed to finish it.

If you're choosing to make a documentary feature, you have to feel like this is a conversation you so desperately need to have, that you feel like people aren't having. You have to know that you absolutely need to contribute to it and that it's urgent that you finish this film. Because without all of those emotions, it would be really difficult to make a documentary.

NFS: So, you got into Sundance, and...?

Mandelup: I feel so shocked that that happened. At a certain point, I just didn't think that that was going to happen. So when we did get in, I was like, "Okay, now we have a first audience," and that was the best feeling ever.

When we got into Sundance, I felt like, "We're good now." And then I was informed that this is the start of the journey—the festival is where it begins. I didn't even think about selling the film. That was kind of a new chapter.

NFS: How did you come to be acquired by Hulu?

Mandelup: That was the greatest thing that ever happened.

Sundance was a taste of the potential audience you can have for your film. You realize people could be talking about your film, people could be writing about your film, people could be interviewing you about your film. That's the dream -- to have a conversation with people about the topic or the theme or the message that you wanted to have a conversation with for all the years you worked on the film. It's like, "Wow, things can work out!" That's crazy.

NFS: Were you involved in the sales process much, or did you mostly just leave that to your rep?

Mandelup: We went into Sundance with publicity and a sales agent — a team to sell the film. It wasn't like I got a call from Hulu one day, you know. So I was kind of involved and not involved at the same time. [The sales agent] was doing her job, touting to the buyers, and then I was doing my job, asking her what's going on with the buyers.

I went into it totally blind. I had no idea how the marketplace works at Sundance. It was the first brush I had with the distribution side. I think about creating films. I think about the message and the imagery. But then there was this new dialogue I was having about distribution deals and platforms. It's important to have that as a filmmaker, but you have to quickly go back to thinking as the filmmaker. You don't want to think too much about that stuff because it can get to your head. Also, you don't make films to think about what buyers want and what distributors want and what will sell at a festival and for how much. You make films because you have an itch you have to scratch — there's something you really need to put out in the world, something that feels personal. The truer that you can stay to that, the more those other things will fall into place because you end up with something that feels honest and genuine.

After the festival, I remember having a feeling of, "I'd like to return to my creative side now."

"When you're getting a film off the ground, everyone wants to know, 'Where's this going? Who are the characters?' Until you get out there and you start exploring, you don't know the answers to those questions."

NFS: Do you have any advice for somebody who might have an itch that they really want to scratch, but they don't really have much else of a roadmap for making a movie?

Mandelup: For a documentary, specifically, I always say start simple. Start in a way that feels manageable with what you can do. Go and film how you can in that moment, because a lot of the early stuff is you figuring out what you're making.

With docs, you don't sit and write a script—you kind of just go and interact with people and write what's happening as you see it, when you see it. So I think you shouldn't over-complicate getting out there, because getting out there is the most important thing. It will help you pitch the film; it'll help you piece together the characters and the arc. When you're getting a film off the ground, everyone wants to know, "Where's this going? Who are the characters?" And until you get out there and you start exploring, you don't know the answers to those questions.

So I think making that first step as simple as possible is the best thing that you can do for yourself. "What do I have access to? Who do I have access to?" Everything is baby steps. You have to kind of work with what's within arm's reach.

NFS: You probably went into filming Jawline with some preconceived notions about the way teenagers relate to technology. What surprised you?

Mandelup: I didn't realize how exacerbated anxiety was right now with teenagers. I got to experience with them firsthand. My crew and I would be filming with Austyn in his room for hours and hours and hours as he did his broadcasts, and we would start to feel crazy. I would be encouraging Austyn to go outside. He was like, "Thank you so much for encouraging me to go outside; I feel so much better now. I didn't realize I just needed to get outside." Sitting in your room by a computer all day just creates so much anxiety!

Anxiety goes hand-in-hand with depression, and technology has heightened all of that. For these teenagers, technology is such an extension of themselves. It's so much of their daily life that sometimes they don't even realize that that's what's giving them anxiety. The anxiety becomes a part of them.

When you're growing up with social media and technology, you need to identify what it's like to not have it, too. Do you feel better without it? That way, you can be in control of managing yourself in relation to that. Because now, as an adult, I can tell myself, "You know what? I don't feel like being on Instagram. I don't think that's good for my mental health. I'm going to get off of it." But when it's ingrained since childhood—when it's a part of your life from the beginning — it's really hard to separate.

'Dead Whisper' score behind the scenes.

'Dead Whisper' score behind the scenes.