About That Insane, Hour-Long, Single-Take, 3D Sequence in 'Long Day's Journey Into Night'

Bi Gan and cinematographer David Chizallet on how they shot one of the most ambitious sequences in modern cinema history.

Dreams are inherently cinematic. They contain the symbolism, tension, confusion, sensuous pleasure, emotional texture, world-building, and surprise factors that make movies irresistible. It's no wonder, then, that dozens of auteurs across the history of cinema have seized on the opportunity to induct the fabric of dreams into movies. From Tarkovsky to Lynch to Buñuel, from Gilliam to Fellini to Linklater, from Hitchcock to Nolan to Verhoeven to Kurosawa, cinematic dreamscapes are as rich and varied as those that have been imagined by people (and animals, too) since time immemorial.

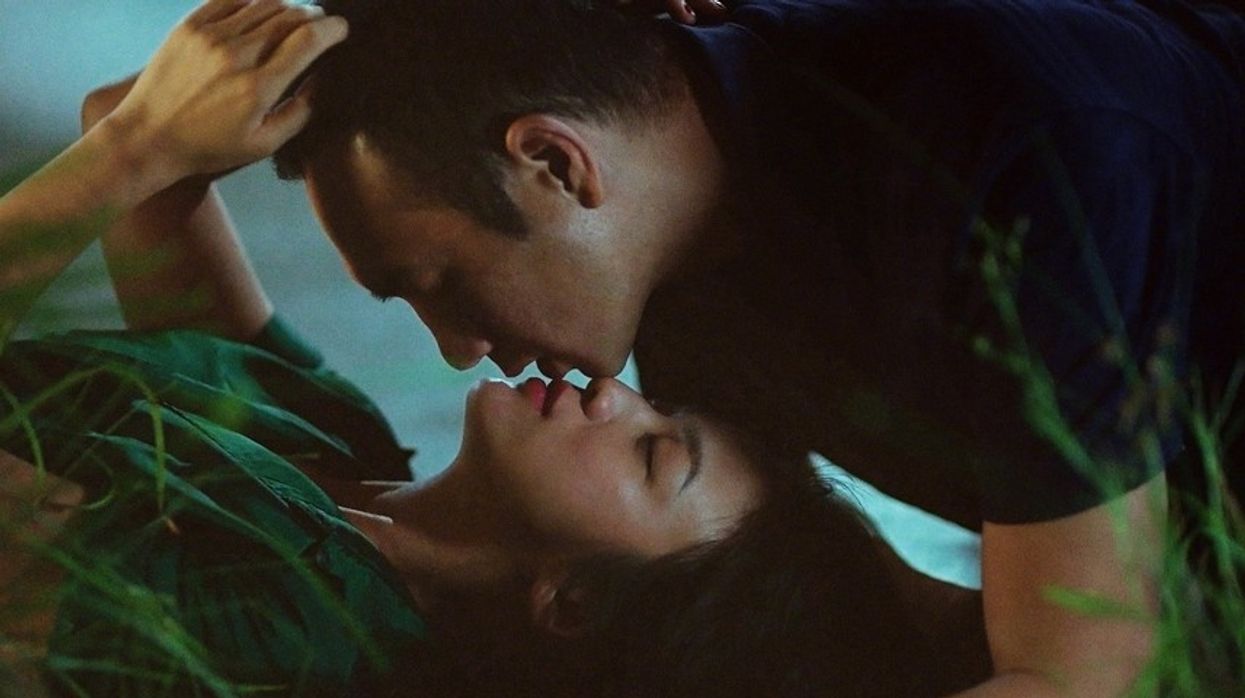

A Long Day's Journey Into Night is the latest entry into the canon of oneiric movies, and, in many ways, the most ambitious effort yet. Chinese director Bi Gan (Kaili Blues) has vivisected his film: the first part is a noir-inspired narrative, and the second, an immersive hour-long sequence, shot in 3D and with a single take. Part one is concerned with introducing us to our protagonist, Luo Hongwu (Huang Jue), who returns to his hometown of Kaili, in Southeast mainland China, to attend his father's funeral. Wandering around town, Luo Hongwu begins to retrieve long-dormant traces of memories. Each place he visits evokes a different element of his past, but he is particularly haunted by an affair he had with a mysterious woman years earlier (Wan Qiwen, played by Tang Wei).

"The goal that Bi was giving us was really quite impossible. We were writing a poem with the camera. "

Part two begins as our hero enters a dingy movie theater, dons a pair of 3D glasses, and takes us on what can only be described as an immersive, surrealistic spatial experience through his dreams, memories, and memories of dreams. The camera, animated by the tension between reality and unreality, follows Luo Hongwu as he travels by car, mining trolley, motorbike, funicular, and on foot through the air, up the stairs of a ruined castle, and through environs that feel endless and ever-changing. The entire film takes place at night, with the neon-drenched streets and beams of moonlight illuminating fragments of an increasingly elliptical story. People often morph into unrecognizable strangers; places feel familiar, yet strange; the skeleton key to Luo Hongwu's desires appears, only to slip through his fingers. It feels like dreaming.

No Film School caught up with Bi and the film's cinematographer, David Chizallet (Mustang), following the theatrical premiere of A Long Day's Journey Into Night. Bi discussed his challenging vision for the 3D sequence and his reasons for shooting a single take. Chizallet, for his part, broke down the technical achievement, which he describes as having been the most daunting and difficult production experience of his life. He describes how the crew spent two months preparing to shoot the single take; how he developed a rig that could carry their RED camera through challenging environments, including a majestic sequence in which it flies through the air; how he and his crew troubleshot difficult transitions, such as employing magnetic devices to connect the camera from cranes to drones; and the many other virtuosic feats involved in bringing A Long Day's Journey Into Night to life. Their conversations, below, have been edited for length and clarity, as neither is a native English speaker.

Bi Gan's Vision

No Film School: How did you conceive of the idea of doing a film that begins in 2D and proceeds to change formats to 3D?

Bi Gan: When I was thinking about how I should structure this film, I was thinking about how it is done in other films—they tend to go from black and white into color. I watched a film that is two parts, where the first part is just the regular film, and the second part actually turns into an animation. My feeling about this particular film is that when suddenly you go from something that is three-dimensional into something that is two-dimensional, it seems to be very, very flat.

What I wanted with my film is to do the opposite. So at the development stage, I decided to create a two-part structure, going from 2D to 3D. The most challenging part was how I was going to make that transition seamlessly.

NFS: How did you ultimately succeed in making that transition fluid?

Gan: I thought that the way I think the best way to go from 2D to 3D is actually to turn to the nature of film itself, narratively speaking. We also play around with the title card, which is strategically placed in the most simple way to announce or to declare a completely different part of the film.

NFS: You mentioned there was a narrative impetus for the 3D sequence. What, specifically, does 3D do for the story in the second part of the film?

Gan: The second part is very much about dream and memory. When people think about memory, they tend to think that memory is fragmented, or fleeting. Many of your memories are interwoven together. I want to create the opposite effect. I wanted to use long takes somehow to go against that preconceived notion of dream and memory as fragmented. I wanted to slow it down, as well, instead of this fleeting shot. I wanted to do one long take.

I also think that it is interesting to create a 3D section for the audience because, at a certain point in the film, they have to collectively put on the 3D glasses. Some of them might not [be familiar with 3D glasses] and they will feel anxious about the right time and the right way to put them on. I think that actually created a certain level of tension by introducing this particular collective behavior that all the filmgoers will do in synchrony.

"It is very, very rare for 100 people to think the same way and achieve the same movement, the same poetry."

NFS: You orchestrated some dreamlike sequences during the long take, such as the camera lifting some characters up into the air at one point, and going into and out of a cave in another scene. These must have been difficult as a director to pull off.

Gan: I now regret that we didn't have some type of documentary crew or cameraperson that recorded how we completed that one long take for the second part of our film. We didn't have the energy to think about the fact that this should be documented. That's a testament to how difficult that long take was for us at the time. All our efforts went into the design and the rehearsal to accomplish this particular feat.

It takes a lot of rehearsals—not only technical rehearsals but also acting rehearsals. We needed to do a lot of that before we actually turned on the camera. We all needed to have a lot of contingencies in terms of how to deal with situations at each location.

In terms of the actual camera we used, we decided to shoot everything in 2D. Then, in post-production, we would convert that into the 3D format. The reason for this was we needed to shoot in very low light conditions, and we needed to move the camera in difficult positions. The actual 3D camera tends to be very, very big and it's not easy to maneuver. The 2D one is definitely lighter and easier to move in a very small environment such as the cave. Another reason was that I liked the effect of 2D converted to 3D. It has a unique quality—the feelings, the atmosphere.

NFS: How many takes did you have to do, in the end?

Gan: There are a few different stages that we tried to capture with that one long take. The first time we did it, we did it for the three different long takes. Unfortunately in all three takes, we didn't manage to finish everything that we tried to do for this particular sequence. Whether it was something that didn't work out in terms of equipment, or because of a performance issue, it just was not as smooth as we wanted it to be.

More than a month later, we decided to [go back] again to accomplish the long take. We tried to do it right this time. And it took five takes. It was not until the last three takes that we managed to complete everything that we planned to have in the sequence. Within those three takes, we decided to choose the last one, which is what you saw on the big screen.

NFS: Based on your previous film, and this one, in particular, you seem to be interested in pushing boundaries of cinema and seeing the way it can be experienced differently by audiences in unconventional ways. How do you think about transforming the cinematic experience for the audience?

Gan: In this stage of my creative life, I tend to be drawn to things on the experimental side. I really want to try new things and bring something fresh to the film medium. I think you can either focus on the content itself, in terms of the narrative and how you tell a story, or the format that you can develop a particular story in. With this film, I did both.

Technology has evolved so much. An 8K resolution camera can shoot in very low light situations. I do think that because of technology, there is a lot of potential to play around with different ways to tell a story. Now, that doesn't mean that there's no merit for people to develop their narrative in a very conventional way. But I want to experiment!

"I really want to try new things and bring something fresh to the film medium. I want to experiment!"

NFS: Can you talk a little about the artistic choices you made in order to realize this Neo-noir aesthetic?

Gan: I relied heavily on the film noir genre for the first half of the film. In fact, I borrowed—appropriated—a lot of unique elements of the genre, including the introduction of the femme fatale. At the same time, I also tried to make it very me in terms of the storytelling.

With this film, the most important thing is actually not the first part, even though that is the first thing people see when they watch the film. What's more important is the 3D part. Only from the so-called Neo-noir genre only you could go into this dreamscape—almost like a fairytale story that I created in 3D. So to me, that genre is just a pretext to get into the juicy part.

DP David Chizallet Brings the 3D Vision to Life

No Film School: I talked to Bi about shooting this hour-long sequence from a directorial perspective. He had a lot of solid reasons for wanting to shoot in 3D.

Chizallet: Bi is not like any other director. Usually, directors are concerned with the narrative: the story is like this, the character is feeling like this. Bi wasn't like this at all. It was really more like putting something poetic on the fiction level. We were writing a poem with the camera. This kind of thinking was really new to me, and I wanted to dedicate myself to achieve it because Bi's vision was so strong and powerful.

NFS: I really want to hear the nuts and bolts about how you made the shot happen. What were some of the most challenging elements of what you pulled off?

Chizallet: We shot in the winter in the south of China. It was very, very cold. So, the first memory is that it was really physical. Every day, I stayed ten hours outside in the cold.

Also, I was the only French guy on the whole crew. My job was more like a manager of the whole crew than just a DP. I had to make a list every day with all the problems and give responsibilities to each department, saying, "You have to fix this," "You have to fix that." I was lucky enough to have one of the best gaffers I have ever met: Wong Kar-Wai's gaffer. He was very original in his way of seeing the light. Color was a big part of the storytelling. He was really crazy about the contrast. Sometimes I was like, "Now, let's use another light." But he would say, "No, no; let's use just one so the contrast is really strong."

"The goal that Bi was giving us was really quite impossible. The shot is one hour, so even the simplest thing would become difficult."

The goal that Bi was giving us [for the 3D sequence] was really quite impossible. The shot is really, really, long—like one hour—so even the simplest thing would become difficult. When we overcame one difficulty, another would [arise]. Like, now the camera is [successfully moving] on the cable—but what about the focus? Do you have to pull focus with your remote, or are you losing focus? Do you have to give the focus to another guy with another remote? How can you make sure that the signal will go to the second remote and not stay with the first one? The pilot for the drone was experiencing this problem. He was watching the drone during the flight, but then he lost sight of it, so we had to give the command to another pilot. It was really, really complicated. All those guys were engineers—in fact, they built a special drone just for the shot.

These engineers also found the solution to making the camera fly with an electromagnet during this really magical moment when [the character] is flying with the cable over the forest, going to the other side of the mountain. We had to synchronize the moment the camera was leaving the cable with the moment the actor was leaving the cable. I really wanted to have a really precise distance between the camera and the character. I had to be precise on little things.

I really love this scene. When the movie premiered in Cannes, I was amazed because the magic is really great.

NFS: What was your technical process for this particular flying sequence?

Chizallet: The basic idea was: How can we move the camera as steadily as possible? We knew that we had to change camera operators three times during the sequence. On the cable, we were not able to operate the camera because of the weight, so a pilot operates the camera through the remote. Then, a second operator took the camera back at the end of the cable. Then, there is the whole movement with the woman who is are flying—that's when the camera operator plugged the camera back on the drone. Then, there is a third operator taking the camera back from the drone and finishing the whole thing.

To make it as steady as possible, we had to use a special rig. It was called the Armor Man. It's a kind of harness with two arms, not one. I was able to support the weight of the camera rig with a gyroscope. The problem is that the electromagnet was on the top of the camera, so when we went to plug the camera into the cable or to the drone, the plate that was connected to the magnet was on the very top of the camera. So, the Steadicam wouldn't work, because the Steadicam holds the camera through the center. We had to build something that would hold the camera from the sides. That's why we used the Armor Man harness.

"I was looking for the most fluid movement possible ... It was really important for me to shoot so that people would not feel the camera at all."

So, we could hold the whole thing from the sides and then lift the camera as high as possible to connect it to the plate that was connected to the electromagnet. Then, an assistant came and switched the electromagnet on or off to plug or unplug the camera from the plate connected to the cable or to the drone. The whole thing was so heavy and difficult. We were lucky to have three camera operators. Also, it was very complicated to [coordinate] the movement with the actors.

The goal was to have a very steady shot while shooting, but also I was saving 10% of the image to stabilize in post. We needed to stabilize the shot as much as possible before the 2D-to-3D operation in post-production. So while shooting, I was looking for the most fluid movement possible. We really couldn't think that there is a camera moving around the actors. It was really important for me to shoot so that people would not feel the camera at all.

NFS: How did you and your gaffer approach lighting differently, knowing that you would transform your shot into 3D in post?

Chizallet: For me, a big problem was the depth of field. Bi's mise-en-scène was to play with what we see and what we don't see: Is there any hint of somebody the character is supposed to know or recognize in the background? Sometimes, we would have people passing by in the background, far from the camera, and we would have to see them.

I had to shoot with a lot of depth of field. I was to avoid all the blur and out of focus parts of the image. So I worked with the images in layers. The first plane is the main character that we follow all the time; then, there is a second layer. It was like a Japanese animation—you know, there is a first layer, then the second layer, and then the background. It was much more interesting to compose the image with layers in focus than to just put the background out of focus all the time.

"I had to work with a lot of light and with a short and wide lens."

I had to work with a lot of light and with a short and wide lens. We worked with a Zeiss super-speed 25 mm and we [shot] everything with it. In the beginning, I was thinking about using a zoom, but the zoom was too heavy. Also, I wanted to use filters, but everything was too heavy because the drone was holding the camera and the cage. That's also why we did not use two cameras for the 3-D—that's what I wanted in the first place, of course, but the weight was very, very complicated to figure out. So I just used one camera and one tiny lens. With the 25 mm at 4, I think we had pretty much the maximum depth of field we could afford, and it was perfect.

I discussed composition with the gaffer and the two other camera operators. Every composition was planned. We were to use the 3-D as much as possible, moving things in the first layer, and in the background also. The two layers were to slide from one to another. It was very interesting to play like that with the moving camera.

Chizallet: The hardest part for me was the central part of the sequence, between the cable part and the drone part. The two actors are talking and moving a lot through a labyrinth. Nobody could know where they were going to go. I had to improvise. I must say that with the weight of everything, improvising was difficult. Bi Gan was really trusting me, so I was under a lot of pressure. But it was also [a lot of] freedom for me. When I did Mustang, I was operating like this—moving with the character. I always tried to adapt and to find the best position and the right distance from the actor. So I was coming back to my roots for this one-hour shot.

It was so fresh for me to experiment with another way of telling a story. At first, I was like, "Are you sure? This is so crazy, but wonderful." Bi was so confident in the fact that the whole process is the story. The one-month preparation is the shot. It was the biggest production experience of my life.

NFS: You spent a month rehearsing and preparing the shot?

Chizallet: Yeah. The first week, we just discussed by daylight, walking on the set and discussing the set decoration. We needed to discuss what we were gonna build for the set, what we're gonna show, what we're gonna avoid. At the same time, I was starting to shape my crew and say, "You are in charge of this, you will be in charge of this." I tried to tell everybody that it was going to be very difficult and to understand that we are not going to work like we would [under normal conditions]. We were to adapt and to find the best way to follow Bi Gan on this.

"It was the biggest production experience of my life ... I don't think I had that kind of pressure on any other movie."

In the first week, we discussed the light and the colors and everything with the gaffer. Also, we figured out the way the camera was going to move and how we could show the action and the dialogue between all the characters in one single shot with no cuts. It was a huge process. "Now the actor can go here, and then we can pan. Then we go to the other actor, and then he will go and sit and we come back."

When we started to work at night, we discussed the contrast and where to put the moon. The moon was so important because you can see the whole village through its very strong illumination.

For the last week, we prepared with the actors. On the very last day, we shot. We had three good rehearsals the night before, but the shot was only okay. We still had timing problems. During the whole shot, there is a party happening in the village, so we had to establish so many cues for the director's assistants. There was an army of people giving cues. Running behind the camera. So funny.

I don't think I had that kind of pressure on any other movie I shot. You know, when I was taking the camera back from the cable [for the drone shot], I knew that there was already 20 minutes of the shot inside the camera I was holding. That was the work of 100 people. You have the camera coming from the sky in your hands and you have to follow the actors. You cannot miss anything. It's like you're shooting live. You really cannot say, "Sorry, I missed that—let's do another one." It's not possible.

Chizallet: During the last take, I heard that there was a problem with the last drone operator. I was running down these crazy stairs in the village in the middle of the mountain. Bi Gan explained to me that the problem was that the horse we had in one shot was too crazy and was jumping in front of the camera. But I think this is the best take. When I saw it, it was like a gift for the shot. We really think that the horse is going to hurt the camera and it will ruin everything. In fact, the horse was holding big baskets full of apples. And in the last part of the movie, the whole ground, there are apples everywhere. It's really beautiful. The apple is one of the symbols of the movie. The actress was playing with the mistake, holding one apple and biting it. Everything was in place, and we were really, really happy.

With the sun coming up after the final take, it was complete madness. It was beautiful. It is very, very rare for 100 people to think the same way and achieve the same movement, the same poetry.

NFS: If you were to give advice to a cinematographer who wants to shoot for something that will end up in 3-D, what would you say is important to remember before going in?

Chizallet: If I could have, I would have used two cameras, of course.

"The image was so clean and flat that one day I took some dust from the ground and I threw it on the lens."

Before production, I talked to my color grader in France. I wanted to make sure that the camera was okay—the resolution, the depth of field. These are the parameters I was really counting on to make sure that people in post-production will have enough information to work on the shot.

When I discussed this with Bi Gan, he said he was not looking for a perfect technical shot. It was more about making it as immersive as possible. It was very important to be always focusing on the emotion, and not at the camera's technical performance.

Sometimes, when I was doing camera tests, I thought the image looked too perfect. The RED camera is a high resolution, and I am used to working with Alexa. But shot was too long for the Alexa. I had to shoot it on the RED. The image was so clean and flat that one day I took some dust from the ground and I threw it on the lens. All the assistant cameras looked at me like they were going to kill me. But I wanted to make it more brutal, more diffused, more accidental. I was looking for an un-sharpened, unclean image. Even if the 3-D was coming later, I really wanted the highlights to be diffused. I wanted to show that this is the narrator's point-of-view. It's not just a digital camera. It's immersive.

NFS: Speaking of immersive, did shooting this film feel like a precursor for working in VR?

Chizallet: I was recently in a Master Class on VR. I was the only DP—there were journalists or graphic artists, but nobody from traditional cinema. It was very interesting to feel that it was such a new tool. People are thinking about how to do it technically. They are not using it as a tool for storytelling now. I will be looking for directors or projects with the idea of using VR as a storytelling tool.

"Bi Gan is, for me, the next step from traditional cinema to the world of VR."

Bi Gan is, for me, the next step from traditional cinema to the world of VR. There is some kind of bridge between traditional cinema and VR with Bi Gan's movie. Regular cinema is also very immersive, but sometimes directors are afraid of using a long-shot to put the audience inside the universe. They want to make sure that people know that it's a story, that they are in the theater and everything.

I usually I don't work with a wide lens like this. When I was doing some research on Birdman and Gravity I discovered that Chivo—Emmanuel Lubezki—worked with a short, wide lens. He uses this tool to make the audience feel like they are inside the story and close to the characters. He always says that when the shot is not working, it's because you are too far from the actor. He's always coming closer, closer, closer with a wide lens. Orson Welles and Stanley Kubrick and Roman Polanski all use wide lenses, too. And they really build worlds. You really feel close to the story.

So when I started thinking about short, wide lenses and coming closer, the step between the Bi Gan movie and VR was really obvious. In this movie, I was using a 25 mm lens, and in VR we always work with very, very short lenses to be able to cover everything. The meat was the same kind of feeling: that you are really inside the world of the story.