How 'MLK/FBI' Editor Laura Tomaselli Found Truth Through Archival Footage

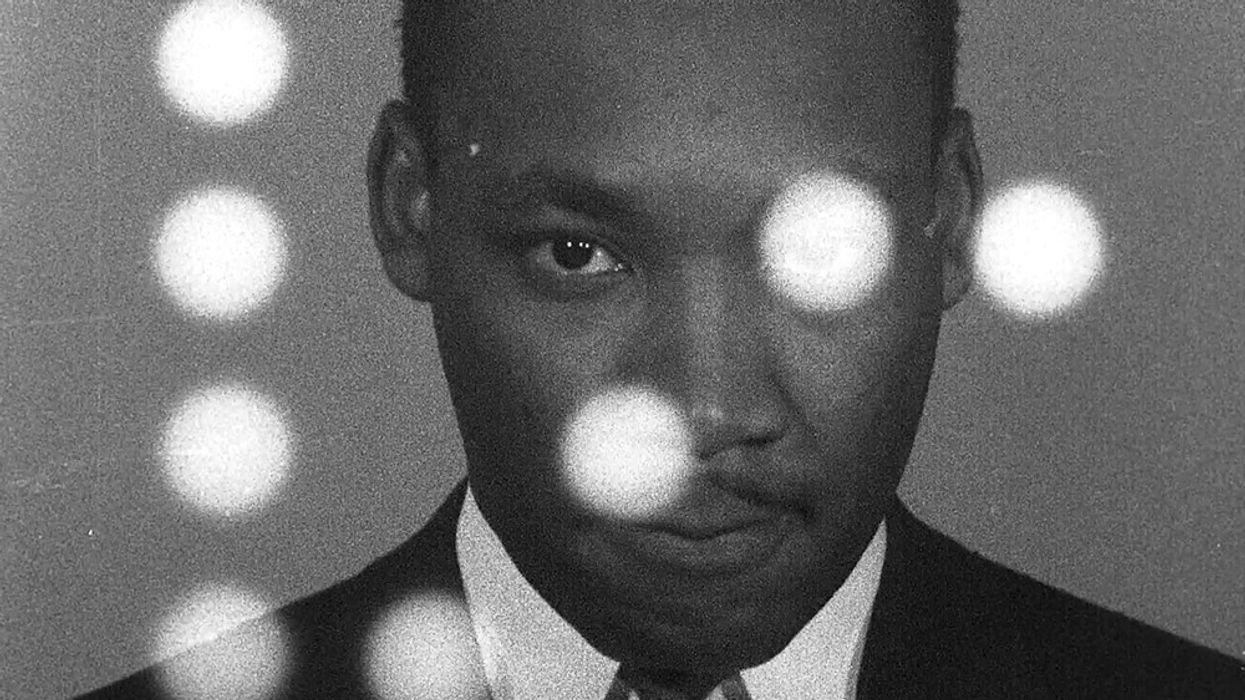

A new documentary exposes how Martin Luther King Jr. was treated by the FBI.

In director Sam Pollard's MLK/FBI, the documentary shines a light on the harassment Martin Luther King Jr. faced from government agencies, who often treated him like an enemy of the state.

The documentary, available to watch on IFC, is based on new information obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, along with restored archival footage. The narrative uncovers J. Edgar Hoover and the Federal Bureau of Investigation's campaign to discredit the civil rights leader and his work from 1955 to 1968, leading up to his assassination.

To craft the film, editor Laura Tomaselli sifted through hundreds of hours of footage to tell the judicious story, which she co-wrote with Benjamin Hedin. Tomaselli sat down with No Film School to offer insight into her process, sharing tips along the way.

No Film School: Was there anything in particular that inspired you to become an editor?

Laura Tomaselli: There isn’t one specific "Aha!" moment when I knew I wanted to be an editor, but I remember being obsessed with the Directors Label DVDs in high school. My brother and I had all three in the first release—Spike Jonze, Michel Gondry, and Chris Cunningham—and would watch them a lot. Those music videos instilled a strong nerdy curiosity in me to learn about whatever inventive techniques they were using.

NFS: Did you connect with director Sam Pollard through a previous gig for MLK/FBI?

Tomaselli: Yes! We first worked together in 2018. I cut the trailer for Acorn and the Firestorm, a great documentary he co-directed with Reuben Atlas. After that project wrapped, he asked if I’d be interested in helping to put together the pitch trailer for MLK/FBI. As taxing as it is to put a pitch together (so much uncertainty!), I had a really positive experience collaborating with Sam and Ben. When they asked me to stay on to edit the feature, it was an easy and enthusiastic yes from me.

NFS: Since you co-wrote the script, does that help you as an editor?

Tomaselli: The construction of MLK/FBI was a process of discovery which I'm sure is true of most archival documentaries. My role as a writer on this film is inextricably linked to my work as the editor. We had an outline going into the rough cut but ended up really creating the interplay between the interviews and archival as we went. We built our rough cut chronologically, with Brian Becker (our incredible archivist) working alongside for a majority of it. This made the whole process dynamic and allowed us the room to adapt to footage we felt was important or hadn’t seen before.

Tomaselli: Working with archival footage is always a double-edged sword. It’s fascinating to fall into these historical rabbit holes but it’s also easy to get swept away by the sheer volume of it. For this project, I used Adobe Premiere Pro to edit. It was a combination of some very methodical work—looking for these specific expository pieces to tell the story, but also collecting moments that felt right tonally or told the story in less direct ways.

On a technical note, when you’re working on an archival project that draws from a more distant time period, you will encounter a veritable buffet of historical codecs and resolutions. They will not play well with each other. Without an AE, I needed to develop an automated system to manage this. A simple hack was to have Brian upload each archival delivery to a directory that I’d marked as a watch folder with custom settings. That made it easy to ensure that all new footage was automatically transcoded to a proxy codec, resized to 1080p, and ready to smoothly edit with.

I think in the end we probably had upwards of a hundred archival sources—ranging from the Library of Congress to the Shelby County Sheriff’s office, where Brian was able to dig up some rarely seen footage of James Earl Ray.

NFS: When did the original footage start coming into frame?

Tomaselli: Sam always knew that he wanted to use original footage in the film. Our shoot happened midway through the edit. There were a handful of notes we wanted to emphasize by not using archival—the FBI agents listening to wiretaps, the bugs in the hotel room lamps, the reel-to-reel tape player. These specifics felt important to help the viewer visualize the story.

NFS: What was the most challenging aspect of the project?

Tomaselli: Working on this during the pandemic was both a blessing and a curse. I got sick early on, and beyond that, there were many days where it was hard to quiet my worries about the world and get into the zone. At the same time, it felt incredibly cathartic to be working on something that felt like it illuminated the present.

NFS: Yikes. Glad to know you're doing better now. MLK is such a profound figure in our history. Was there anything that surprised you about him during the process?

Tomaselli: Dr. King’s unending poise and civility in the face of everything he dealt with never ceased to amaze me.

NFS: Curious, how did music fit into the cut?

Tomaselli: Music is central to my edit process! I do a lot of music research early on, building a sort of mood board for the tone of whatever I’m working on—even if I never use it. In this instance, both the Mahalia Jackson track under the titles and the Harry Belafonte track during the credits were pieces of music we all loved really early on.

For the score, we worked with the very talented Gerald Clayton. It was a dynamic back and forth. He created original compositions and themes and then he and I would play with different arrangements to suit different moments in the film. A good example of this is the section where we introduce J. Edgar Hoover—the bass line enters first and then we gradually introduce all the other instruments. It was really wonderful to be able to collaborate with Gerald in this way.

Tomaselli: For directors, unless you specifically want your editor to be a fresh set of eyes, I think it’s great to get them involved as early on in the process as possible. Beyond creating space for their feedback or concerns, you’re also allowing them a window into what you want the film to be like at the outset. So much can change during production but having that additional context can be really helpful for an editor to figure out potential approaches before the edit officially kicks off. Very few things can be completely “fixed in post.”

NFS: Any tips you can share about the interview process to land a job as an editor?

Tomaselli: At the risk of sounding like a motivational poster, I think it’s important to be prepared, be confident, and be relaxed. Ages ago, I remember showing up for an interview thinking it was going to be a "what’s your biggest strength" vibe, and instead it was the entire office at a sushi restaurant asking me "what my process looks like." I had no idea what to say because I wasn’t sure that I had a process at all! Take yourself seriously. I wish I could tell my younger self that.