Steven Soderbergh on How He Saved 'The Limey' From Being a Disaster

The Limey, Steven Soderbergh's hard boiled classic, turns 20 this year and has (finally) gotten a proper 4K HD digital release this week (courtesy of Lionsgate).

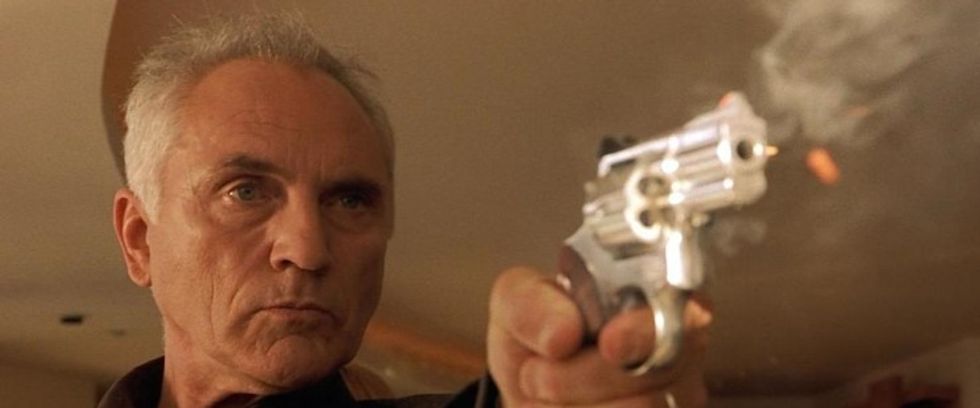

In honor of The Limey's 20th anniversary, the filmmaker has given a handful of interviews about the process of making the film (about a criminal, played by Terence Stamp, who travels to Los Angeles to avenge the death of his daughter) and how its very essence was finally captured late into post production.

When the film was first released, it was hailed as an experimental film, almost cubist in its construction -- but it turns out that this was more of a desperate necessity and less of a predetermined design.

In a recent interview with Rolling Stone, Soderbergh admits that the script, by his Kafka collaborator Lem Dobbs (the two would go on to work on the similarly underrated Haywire together) was written as a linear narrative -- moving swiftly from point A to point B. He said that the decision to reshuffle was "generated out of a sense of panic."

What caused that panic? The director said that the first time they screened the linear cut of the film, as it had been written, "it just didn't work. [Editor] Sarah Flack and I had to sit down and kind of start over. [Pause] Actually, we literally had to start over. There was no kind of.”

Soderbergh had to go back and re-conceptualize the entire piece.

"Given its premise, it seemed there was some possibility to recraft it into a memory piece. To make that work, we ended doing a couple more of days’ worth of shooting, to gather more abstract material to layer in: the plane, Peter sitting in the cabin and looking at the wind chimes," Soderbergh explained to Rolling Stone. "All these sort of contemplative shots -- we needed that material to make this version play."

The filmmaker explained that the experience was "worrying" because he'd just made his way back into the Hollywood studio fold with the release of 1998's Out of Sight. Ten years earlier, he'd been the toast of the independent movie scene, thanks to his debut feature sex, lies, and videotape, but had spent the following decade noodling around in films that might have been creative triumphs, but they didn't do anything to capture the imagination of critics or audiences (things like the black-and-white Kafka and coming-of-age tale King of the Hill).

He fretted that, just a year after finally returning to the scene, he'd be ostracized again. "I wanted to keep busy, keep the momentum going, keep making a movie every nine months. So to put this movie together, show it to a room full of friends and then go, Oh, this is really not working. . . . We spent a few days just thinking, 'what is salvageable here? What can we do with what we have?'"

It even sullied what should have been triumph, as he explained to the magazine. "I think it was [producer] Stacey Sher who called me in the middle of this and told me that Out of Sight had just won the National Society of Film Critics award for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Screenplay. And I just went, “Uh, uh-huh, OK,” and hung up. [Laughs] I mean, I could not have cared less at that moment. What should have been this incredible moment just became subsumed by this dark cloud of concern."

"There were all these conversations about layering in these shots, how we were going to establish things, all of that. A lot of trial and error. When you’re asking people to embrace this sort of polyphonic structure, you have to judge how much is too much," Soderbergh said. "We had a lot of in-progress screenings because we thought, well, to know if this works, someone has to see the whole thing. It’s like: Here’s an image that we use FIVE times. You have to be certain, should it be five times? And where precisely should they occur? You use a recurrent, pregnant moment at the wrong point — you might as well stop the whole film. You’ve thrown everything off. But then you know it’s throwing people off, so you can go back and say, 'Ok, we were good here, let’s start again.' There was a lot of discussion."

What's incredible about this whole reveal is how intrinsically the fragmented structure of The Limey feels when you watch it.

Nobody who saw the movie in 1999 thought, Oh, this was a total last-minute salvage job. But it happens more often than you'd think.

One of the many amazing revelations in Oscar-winning editor Paul Hirsch's new memoir, A Long Time Ago in a Cutting Room Far, Far Away, is that the emotional climax of John Hughes' Planes, Trains and Automobiles (when Steve Martin realizes that John Candy is homeless and that his wife had died, and decides to come back and get him for Thanksgiving) was totally figured out after-the-fact. And yet you would never know it.

Just like Terence Stamp's time-scrambled trip to Los Angeles, it was conceived away from the script and in the midst of a lengthy post-production process.

The Limey is on HD digital Tuesday.