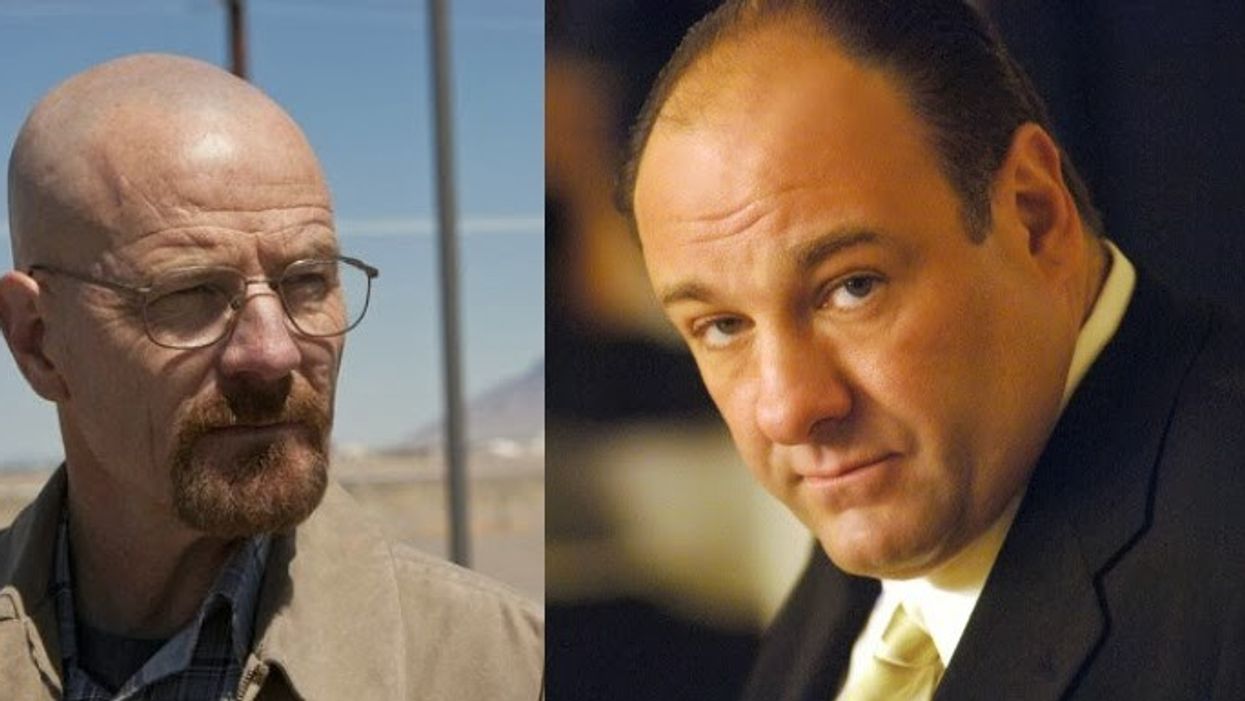

A few months ago, I wrote a post called The Story of Story, which attempted to explain, in as simple a way as the subject can bear, the roots of narrative structure, and specifically, how these roots were planted several thousand years ago, in ancient Greece, and have been passed down through the works of Aristotle. Today, I'll begin with a sort of riddle: what do David Chase, creator of The Sopranos, and Vince Gilligan, the mad genius behind Breaking Bad, have in common? That's easy enough, you say. Well, then, what if I asked how they differed? It's not an impossible riddle, but its answer just might be the key to the next story hurdle you have to surmount. And it might be closer than you think.

The Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges observed, "art is fire plus algebra." Borges understood that though it is the fire which provides the spark with which we can see the edifice of our narrative, it is only math which will get us to the top of our story, so that we are firmly in command of the events on the page, looking down on the world we have made. But what, you may ask, does this have to do with David Chase and Vince Gilligan? Well, it turns out, a good deal. Because as science is put to ever more novel purposes every day, it is now beginning to explore the roots of narrative, and just what makes for a satisfying story in the brains of those engaged in the narrative.

Do you remember the series finale of The Sopranos? I do. And I can hazard a guess that when the chugging, optimistic chords of Journey filled the soundtrack (and henceforth, every karaoke room, every night, forever) and the screen was filled with the family Soprano, finally reconciled over onion rings (if only for a moment), no one was expecting what seemed like a cable outage. Howls went up from the faithful, once at the blackout, and twice when they realized what had actually happened (which was? Bueller?) David Chase, never one to explain himself, remained tightlipped, though did say, according to The New Republic: “'Well -- the idea was he would get killed in a diner, or not get killed, or somebody would try to kill him, or there’d be an attack.' He added, “I’m not trying to be coy about this. I really am not.'" Which is, just, wow. Chase: 1, Everyone Else: 0.

Most viewers came to the conclusion that the abrupt cut to black was symbolic of Tony's snuffed candle (which seems to suggest that in the 21st century, the best metaphor for death is a cable outage), and the quick cuts to men moving around the diner seemed to imply that Tony, looking up at Meadow, was dispatched in the same way he had ordered the deaths of so many others, oblivious to the fate at the back of his head. So why did this irk almost everyone? It provoked at least one 40,000 word essay, a considerable amount of grousing, and endless speculation which carried an unspoken implication that there was something to speculate about, that the cut to nothing was not an terminus, but a clue. But Chase refused to do more than cryptically prevaricate (see above) and the sense of dissatisfaction among many viewers persisted.

The cause of this dissatisfaction can, perhaps, be located in one word (with several syllables): ambiguity. Like any creator of a fictional universe, Chase had played god for years, and his god was capricious, 'realistic,' more true to life than the more manichean force behind other shows concerned with crime and its discontents. David Chase's universe was run by a disinterested deity, almost like chance, who was forever cutting your cable at the most inconvenient times. Life is messy. It ends in split seconds. Whaddya want? But this was the most influential show on TV in years, and for it to end as it did caused no small end of grief to those who wanted closure. People acted as though a great injustice had been done. But why? I know the answer might seem obvious, but stick with me.

It can be approached, obliquely, by looking into the series finale of another monstrous hit, this one a tale not of an unrepentant mobster, but a good man, a sick man who discovers at the brink of death a power within himself that turns him into a figure of Shakespearean villainy, greed and evil, consumed with power for its own sake (the show makes it plain that after a point, even mammon holds no interest for him, except as a way of keeping score). If Tony Soprano was Sonny Corleone, then Walter White in the first episodes of Breaking Bad was Michael, fresh out of the army, innocent, naive to the evils of the world. But like a comic book villain, he would discover his secret powers, and they would turn him into a monster, rapacious and hungry for nothing but power for its own sake. Tony Soprano was a depressive mobster, a blue collar guy and metaphor for the helplessness of the working man. See, the show seemed to say? Even a mob boss can't get a break. Walter White, on the other hand, was some kind of beast, a Southwestern Macbeth.

Now look at the contrast between the two endings of the two biggest crime shows of the early 21st century. The Sopranos finale is still an object of contention among some critics, though, really, it's nice outside, and these critics should probably go for a bike ride, while the BB finale was the antithesis of its East Coast counterpart and universally hailed as a triumph of dramatic storytelling. Walter White returned home to settle the score, and boy, he settled every score; not one loose end was left loosened. In a last, and possibly redeeming gesture, he did save Jesse from the fate of neo-Nazi meth cook. (I say possibly because Walter messed up a lot of lives, not to mention ending several for no reason, and that's not including the thousands of poor souls who died at the hands of his blue meth. So, I mean, redemptive is relative. I'm glad Jesse is cool, though.)

Even though the BB finale has holes you could drive a mobile home meth lab through (such as, say, how the most wanted man just sneaks back into town, making no effort to disguise himself, going where he pleases, meeting and poisoning people in public, etc.) before using his knowledge of physics and automated machine guns to dispatch a room of neo-Nazis who happened to be right where they were supposed to be. And yet, the critics and fans were almost beside themselves with rapture. "Who cares?! Did you see that machine gun?!" cried America (and verily, what a machine gun it was).

It doesn't take a master of dramaturgy to elucidate the difference between the two finales. Here, there was no ambiguity. There was anti-ambiguity. Now, it can be argued (has been argued) that ambiguity is a European dish, the onion rings in drama's app sampler; this assumes that European films are more inclined to accept ambiguity. And that what Gilligan gave us was a big ol' USA finale, all fireworks and the fourth of July. The bad guy dies, but we see him dead, and we know that the story is over. We know how each of the main characters ended up, but what we don't know is why this satisfied everyone so much?

Lisa Cron, author of Wired For Story: The Writer's Guide to Using Brain Science to Hook the Reader from the Very First Sentence, has done some research into this, and in this TED talk, she delivers some of her findings:

According to Cron:

Fictional narratives supply us with a mental catalogue of the fatal conundrums we might face someday and the outcomes of strategies we could deploy in them -- Not only do we crave story, but we have very specific hardwired expectations for every story we read, even though -- and here’s the kicker -- chances are next to nil that the average reader could tell you what those expectations are.

Now, lest you accuse me of being more opaque than the Sopranos finale, let me share what Cron defines as the functions of story:

“What happens” is the plot. “Someone” is the protagonist. The “goal” is what’s known as the story question. And “how he or she changes” is what the story itself is actually about -- As counterintuitive as it may sound, a story is not about the plot or even what happens in it. Stories are about how we, rather than the world around us, change. They grab us only when they allow us to experience how it would feel to navigate the plot.

That is to say, in a certain kind of story (not all stories), the success or failure of the narrative is in direct proportion to the narrative's ability to bring the viewer into the shoes of the main character. By that logic, the Sopranos finale frustrated so many because it refused to capitulate to expectation. In point of fact, it actively thwarted it. Tony was a distant character, a cipher, much of the time, and the last scene of the show gave us no "breadcrumbs," as she puts it, to follow. Chase was after the messiness of life, and Gilligan, it could be said, was after the cleanliness of death.

And yet, at the bottom of it all, underneath the seasons and reels of real and imagined bloodshed, we can hear the voice of one man. It's a familiar voice, and belongs to none other than that Ancient Greek Aaron Spelling, Aristotle, who taught that by witnessing a tragedy, the audience would undergo a salubrious reaction known as purging, or, in Attic Greek, katharsis. And in lab experiments, it was found that viewers experienced a positive emotional response when the protagonist did well, even if they were doing, well, terrible things. So we're all implicated. And that's why we can't have nice things, guys.

Furthermore, if we identify with the protagonist, and that protagonist happens to be Walt, then our moral judgments are suspended because, well, he's us, isn't he? Mary Beth Oliver, a professor of media studies at Pennsylvania State University, has in fact researched many eudaimonic rewards of watching depressing, stressful, or even horrific television.

Eudaimonia is an experience that meaningfulness [sic], insight, and emotions that put us in touch with our own humanity. Eudaimonia might not make us happy, but it can enrich us, leave us feeling fulfilled, touched, and perhaps even teach us something about ourselves.

I'm afraid this post is more of a Sopranos ending than a Breaking Bad. I have no easy answers, though I do know this: an audience will gladly sit down for two hours, two months, or two years, spending time in the company of the most repugnant characters, just so long as those characters allow us to feel more alive. And that's what story does. It teaches us how to live; when Walt dies, we can feel secure knowing that, as in Oedipus Rex, balance has been restored to the universe.

Not much has changed in all these thousands of years. We like to watch. Now it's up to you to give us something to root for. Or against.

Links:

- How Vince Gilligan Used Science to Create the Perfect Ending for Breaking Bad -- Motherboard

- TV So Good It Hurts: The Psychology of Breaking Bad -- Scientific American