Fixing It in Post: A Case Study in Correcting Shooting Mistakes in the Edit

"We'll fix it in post." It's one of the most dreaded phrases to say in production. But what if you've already screwed things up and you have no choice?

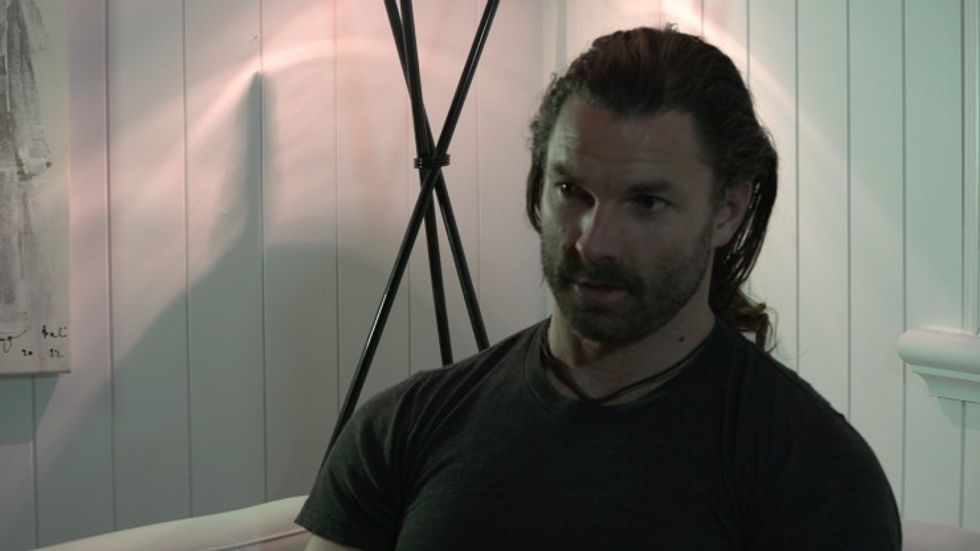

Director Lachlan Huddy faced just such a situation — rather, several of them —while shooting his film Guy's Trade. Below, he details how the seemingly irreparable mistakes he made while filming became salvageable once the project moved into post.

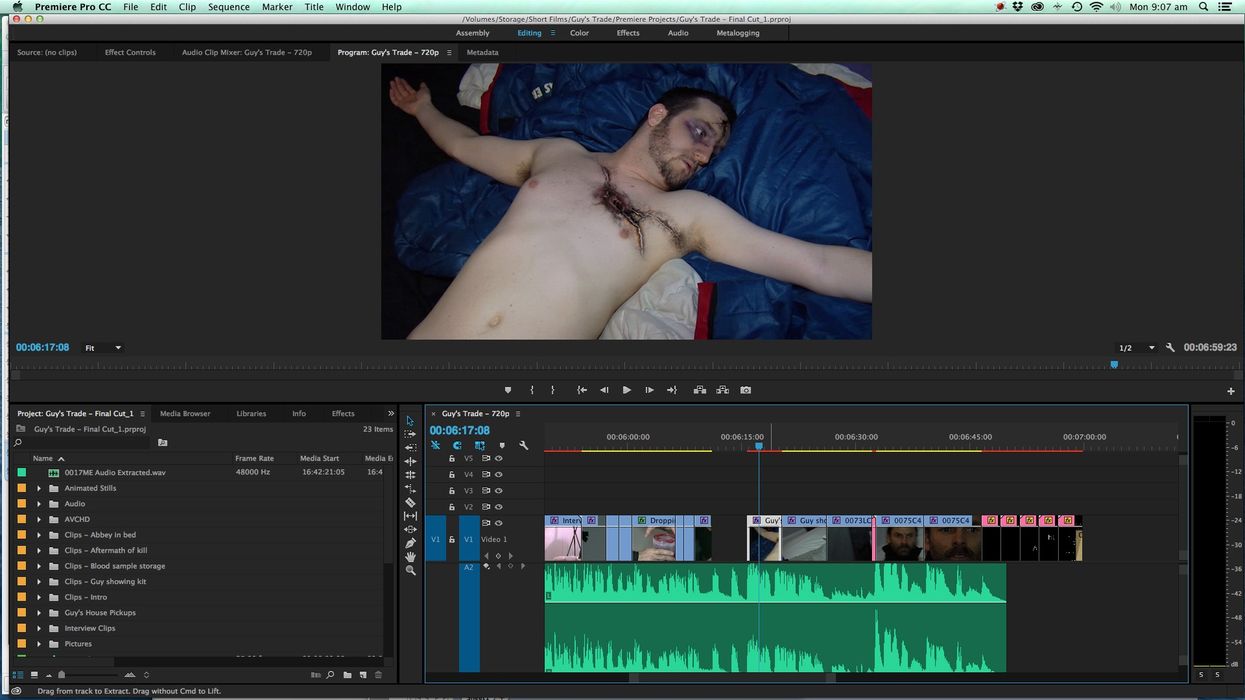

We shot Guy’s Trade, our Tropfest-shortlisted pseudo-documentary about a state-employed vampire hunter, in one day on two mismatched cameras, capturing audio between my FS-700’s onboard recorder and a five-year-old Fostex, and lighting on the fly with three of the crappiest eBay LEDs $90 could buy. It was a raw, scrappy, invigorating shoot. We ran. We gunned.

We screwed some things up.

Botched coverage. Blown focus. Uncooperative props.

In the edit, the only choice was to think sideways and get creative. Check out our short and then read on to three of the biggest screw-ups we had to conquer to get it on-screen:

"The A-Cam blew focus and the B-Cam ran out."

The Problem

We rolled two cameras across the shoot: a Sony FS-700 and Panasonic HVX200. Lead actor Guy Williams gave me reams of material in the improvised talking-head interview, and the HVX’s P2 card filled up with twenty minutes still to go. No big deal — I’d stick to the FS-700 footage for the remainder.

Except that I got into the edit and discovered the FS-700 footage was hopelessly soft.

Ugh.

The situation: no useable footage for the emotional crux of our story.

The Fix

Here's what we did have: crisp audio, care of the Fostex recorder, and piles of footage from earlier in the shoot. Filmmaking is jigsaw puzzling — finding pieces that fit together and making them fit.

After some scouring, I saw a way to run the audio over repurposed footage of our slain vampire to build a voiceover section as a substitute for my original talking-head vision for the scene. I rolled up my editor’s sleeves. I shifted the footage of Jake from the start to the end, added the voiceover, and cut to black on an ominous sound effect and Guy’s grave line delivery to transition into the scene. This retained the emotional impact of Guy’s hollow-eyed face as he discusses the killing of his own finacée while neatly sidestepping the need to actually show it. No god-awful soft footage. Story intact.

I’ve found again and again that the difference between a successful cut and a failed one is often a matter of frames.

"I forgot to capture a crucial close-up."

The Problem

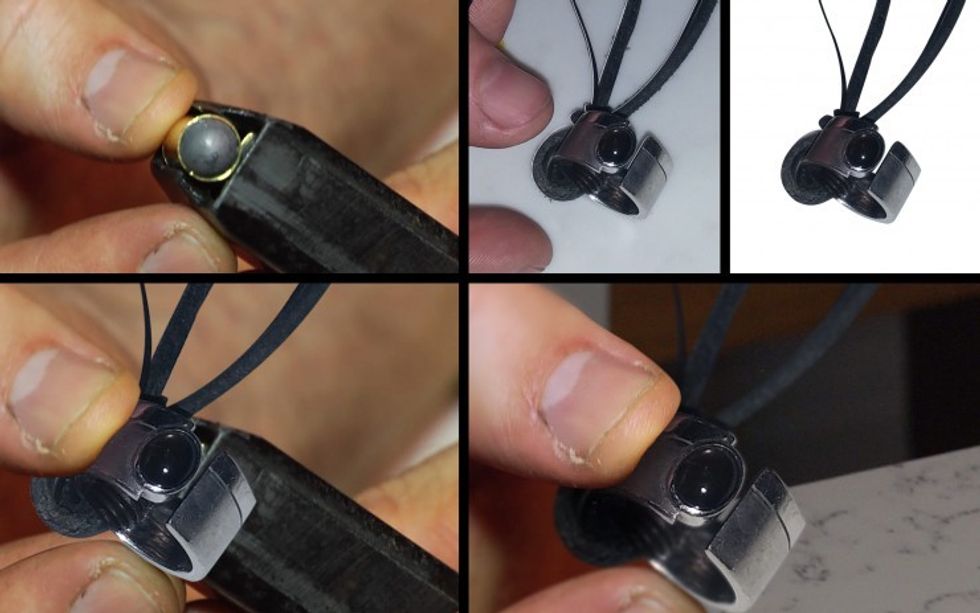

The shoot was a hundred-yard dash so it was inevitable a shot or two would slip my mind, but a close-up of Guy showing his engagement ring should not have been one of those. All we had for this pivotal detail was the interview footage: far too wide for even the sharpest-eyed audience member to discern what Guy was holding.

The Fix

Again, it was a process of jigsaw puzzling. There was a gap in the picture. How could I use the pieces we already had to fill it?

Archival stills are an important aspect of the short, and early in the process I’d landed on a technique I’d learned here on No Film School which animates still images in three-dimensional space to amplify their visual energy. I combed our footage to find an extreme close-up of Guy holding a magazine of silver bullets up to camera. The way he pinched the top of the magazine — I could work with this.

I pulled a still, brought it into Photoshop and isolated Guy’s hand, deleting everything else — magazine, bullets, background. I then took a photo of the engagement ring (with my HTC smartphone), isolated that and dropped it onto the still of Guy’s hand. A little masking, color-matching, shadow addition and.... voila! We now had a still of Guy holding his engagement ring in a glorious ECU.

I applied the animation technique to the still in After Effects and it slotted seamlessly into our story.

"Crap, that reminds me – we weren’t able to get another crucial close-up!"

The Problem

A key aspect of the story is Guy’s collection of vampire blood samples. I was only able to procure a set of insulin injection syringes during our limited pre-production and, it turns out, these are unsuitable for extraction; the needles were too thin to allow the stage blood to be drawn. There goes that visceral close-up of blood creeping into the barrel.

The Fix

The inimitable Sidney Lumet, in his book Making Movies, advises that no one shot is all-important in a film; rather, it’s the way each shot interacts with what comes before and after. Audiences connect the pieces that we show them.

While the shot didn’t work in whole, we had recorded the close-up of Guy drawing the syringe’s plunger back. I’ve found again and again that the difference between a successful cut and a failed one is often a matter of frames.

On the very last frame before the audience would see that no blood was filling the syringe, I cut to a shot of Guy inspecting the sample in a plastic container. Taken together, those shots told the audience: “He just drew blood. Here’s where it ended up.” To ice the cake, I ensured the tempo of the scene was nice and brisk.

The upshot? Most viewers I’ve spoken with swear they saw blood enter the syringe.

Final Thoughts

As you can see, the post-production on Guy’s Trade was a bracing, challenging affair — and delightful for that reason. It reminded me why I love making films: the way it quickens the mind, imposes problem-solving, demands creativity. There really is nothing like doing what we do.

What problems have you been forced to solve creatively in the course of your filmmaking? Were they during production itself or later in the edit?

Courtesy of guest author Lachlan Huddy.