Here's Why Blocking is Essential—And How to Use it to Visually Tell Your Story

Blocking is much more important than you might think.

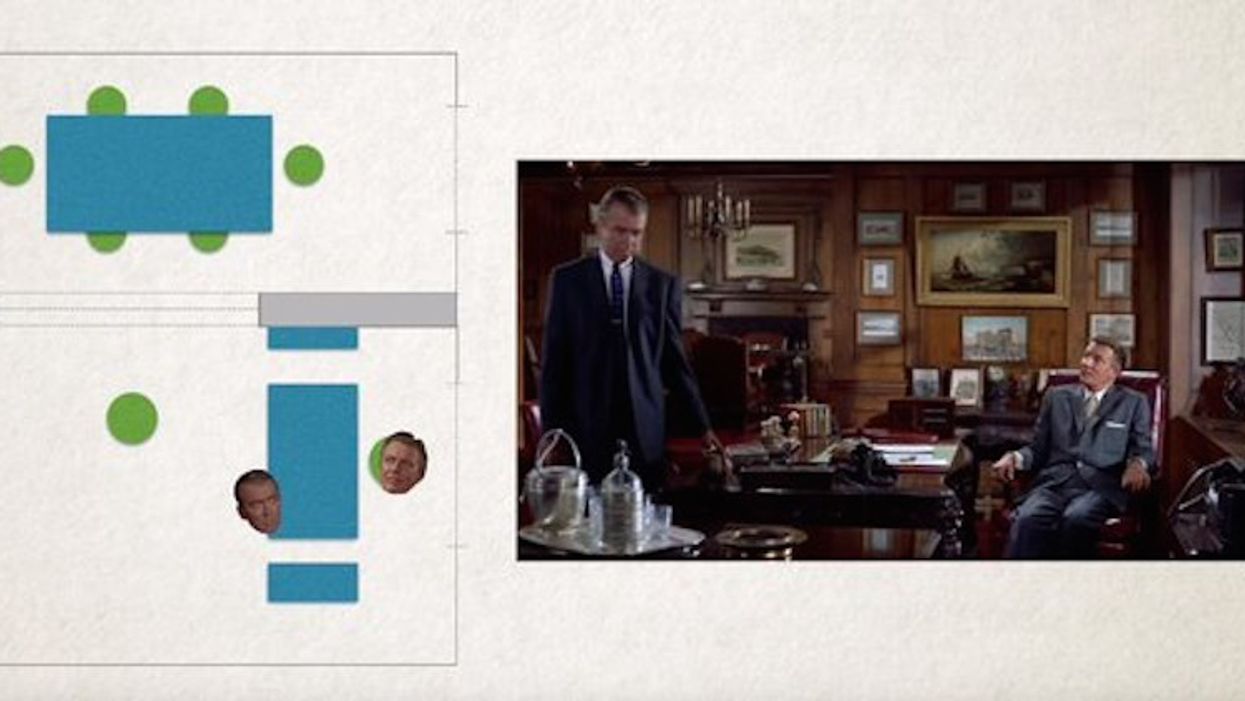

Blocking in cinema is the use of movement and proportion of people and objects within the frame's space. The term comes from theater, but in movies, the camera can travel through cinematic space, making blocking a powerful tool. In this video essay, Evan Puschak (Nerdwriter) breaks down a scene from Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo, and, as you can see, blocking shapes the scene dramatically.

As Puschak demonstrates, blocking gives subtext to a seemingly innocuous scene. Early in the film, Jimmy Stewart's character visits an old friend; while their encounter begins with Stewart controlling the space as he walks around freely and asks questions, the power radius slowly begins to shift and Stewart becomes the one who is controlled. Also of note: in the film, the camera is a sort of proxy character; its movement in the cinematic space is just as important as a character's, sometimes even more so.

The blocking of the characters, combined with skillful editing, makes for a scene that operates on multiple levels at once, fooling us while also priming us for later events.

An audience seeing the film for the first time is busy taking in the surface-level exposition, but all the while Hitchcock's blocking subtly communicates the power shift away from Stewart. Though it's never explicitly stated, the tables have turned: Stewart becomes the one who sits, reduced in importance, and his mild-mannered "friend" is suddenly dominant within the frame. The blocking of the characters, combined with skillful editing, makes for a scene that operates on multiple levels at once, fooling us while also priming us for later events.

A more recent example of the power of blocking can be found in a simple camera movement near the end of the final episode of Breaking Bad. Film editor, blogger, and all-around awesome dude Vashi Nedomansky made the excellent video below, which dissects what at first glance seems like a utilitarian shot:

Vashi writes:

In the final episode of Breaking Bad, there are two shots in a pivotal scene that are perfect examples of how to use camera movement to amplify the narrative and surprise the audience. With one simple pan and one simple dolly…there is a set-up and shortly after, a dramatic payoff. The scene at first appears to be just conveying information to the viewer. Then, with one pan and one dolly move, the scene is flipped on its head and is seen in a whole new light. This could only happen through writing, direction, set design, and camera movement working in unison. A Steadicam or crane shot through a window could never have achieved the emotional impact of a simple pan and dolly.

Visual storytelling is so unique and powerful because it uses reality to change reality. Like a photograph, film is made from life, but it's a reality unfrozen from its chains; a reality unfolding in time, familiar and alien at once. (There's a reason that movies are compared so often to dreams.) Theater, music, painting, photography, lived experience— all of these are cinema's fodder. By mastering its techniques, filmmakers become artists. A scene blocked in harmony with the other elements of the work not only moves people and objects through space but also moves the audience.

Source: Nerdwriter