This Video Essay Breaks Down the Eyes of 'The Silence of the Lambs'

Through camera angles, The Silence of the Lambs asserts its powerful point of view.

Movies make voyeurs of us all; in a dark theater, we watch, spying on other people's lives. But the audience only sees what the filmmakers let them. This video essay shows how, through artful deployment of camera angles, The Silence of the Lambs establishes its POV while subverting the film's genre trappings.

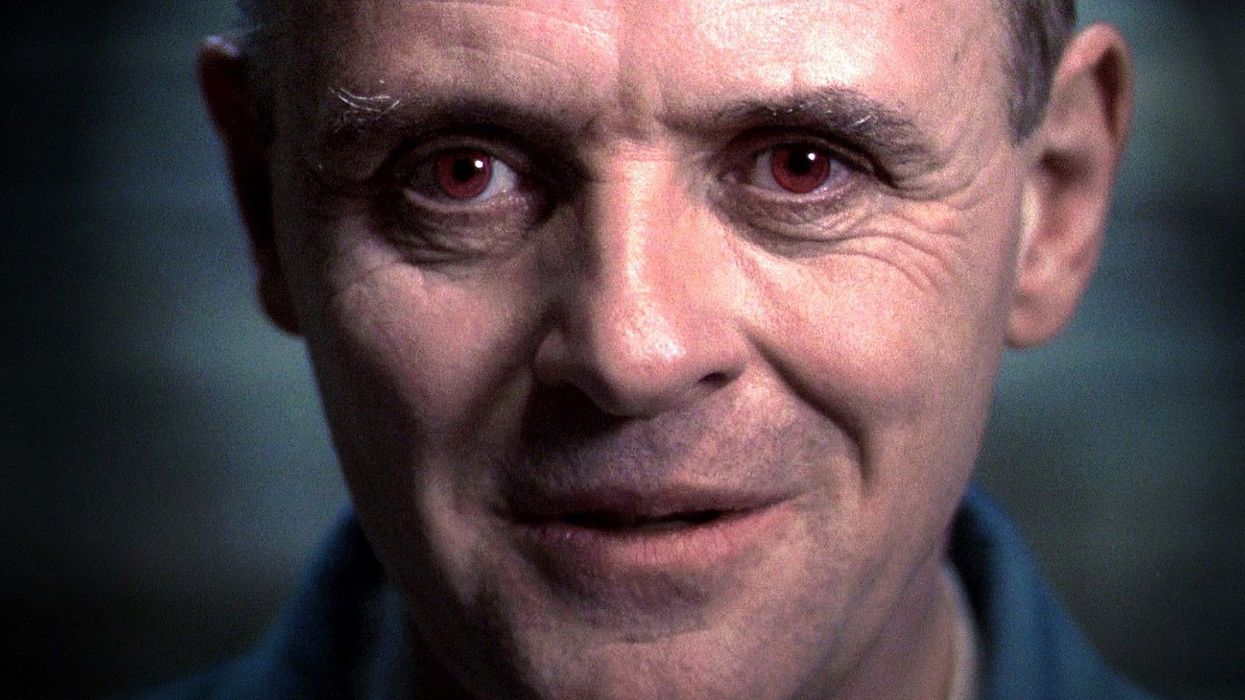

Upon its release, Jonathan Demme's 1991 adaptation of Thomas Harris's novel was hailed as an instant classic. This was mostly credited to Anthony Hopkins' performance as the post-modern cinematic embodiment of evil, Hannibal Lecter. But in this video essay, Steven Benedict argues that it's because the film visualizes its themes before it verbalizes them, and in the process upends many of the tropes found in other horror films.

Take a look:

In Silence of the Lambs, the act of looking sets the plot in motion. Clarice Starling is a young student at the FBI Academy; she is the "point of view character," the moral center of the film. But how do Demme and cinematographer Tak Fujimoto establish this cinematically?

Why? It has to do with gaze theory, which, in brief, thinks of film in psychoanalytic terms: as a scopophilic activity, or an activity characterized by pleasure in the act of looking. Male gaze theory posits that in film, women have traditionally been elevated to spectacle, while men have been the watchers. The audience feels the discomfort of Foster's character as she is objectified by the people she meets on her journey. But instead of being a victim or an object, as in so many other horror films (Benedict references, among others, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre), Clarice is the subject. Her agency is part of what makes the film so unique.

When Starling speaks to someone, her eyeline is slightly off-center, in line with "traditional" film grammar. This establishes her as the point of view character. The audience identifies with her unconsciously, which allows the viewer to take on her simple moral code.

The most powerful eyes in the film belong, of course, to Hannibal Lecter. When Lecter meets Starling for the first time, the two are not separated by bars, as in a traditional prison, but by plexiglass; nothing gets in the way of his gaze, directed at Foster's character and at the audience.

Silence of the Lambs manages to be intensely unnerving and frightening without showing much violence at all.

Lecter's character is a black hole, and in his empty eyes the audience can project all their fears. This is how the film manages to be intensely unnerving and frightening without showing much violence at all. In fact, it isn't until 70 minutes in that any act of violence occurs (Hopkins' bloody escape from the Baltimore museum).

Shortly before that, though, Lecter gives Starling the key to the film when he explains to her the act of looking, which leads to coveting.

Benedict's essay also goes into more detail about the male gaze theory in relation to horror films, including Michael Powell's Peeping Tom, where the killer literally films his victims, making the metaphor of photography as violence (shooting pictures, etc.) a visceral reality.