RIP, Curtis Hanson: Why the Self-Made Director Should be a Lesson to Aspiring Filmmakers

Curtis Hanson, director of L.A. Confidential and Wonder Boys, died yesterday. He slogged through the Hollywood system to get his voice heard.

A handsome man with a thin face—young, unknown Guy Pearce—excitement barely masked by a gung-ho professionalism and ferocity, tells a cop that no one is to walk through the front door of the diner next to him. The fresh-faced detective opens the door to the diner with a handkerchief, noticing an eerie quiet first, and then the food still simmering on the fry cook's stove top. The score rumbles and shakes. Something is wrong here. The camera slowly pans across the abandoned lunch counter and locates the dead cook, a gun next to him on the floor. The cash register's been emptied. The detective tiptoes down the hall, discovering bloodstains on the wall and the floor. Someone's been dragged into the back of the restaurant. Piano starts nervously ascending and descending. Everyone knows what that sound means: This peppy, brusque film noir has become a horror movie. The detective pushes past one door into a back hallway before locating the men's room. Handkerchief in place, he shoves the lavatory door open, revealing blood spray all over the wall, five bodies on the floor, and lots more gore pooling on the dirty tile beneath.

Hanson should be a lesson to every young filmmaker who doesn't know how she'll be able to break into the business.

It's in this moment that L.A. Confidential changes polarity. Only a director with a knack for horror and thrillers could ever have orchestrated this scene with such confidence. Only a born filmmaker could slip it in as an act break, as a counterpoint to the breezy tone he established in the first half hour of his satirical crime story, and not lose momentum. Only Curtis Hanson at that moment in his career could have made a film this perfect.

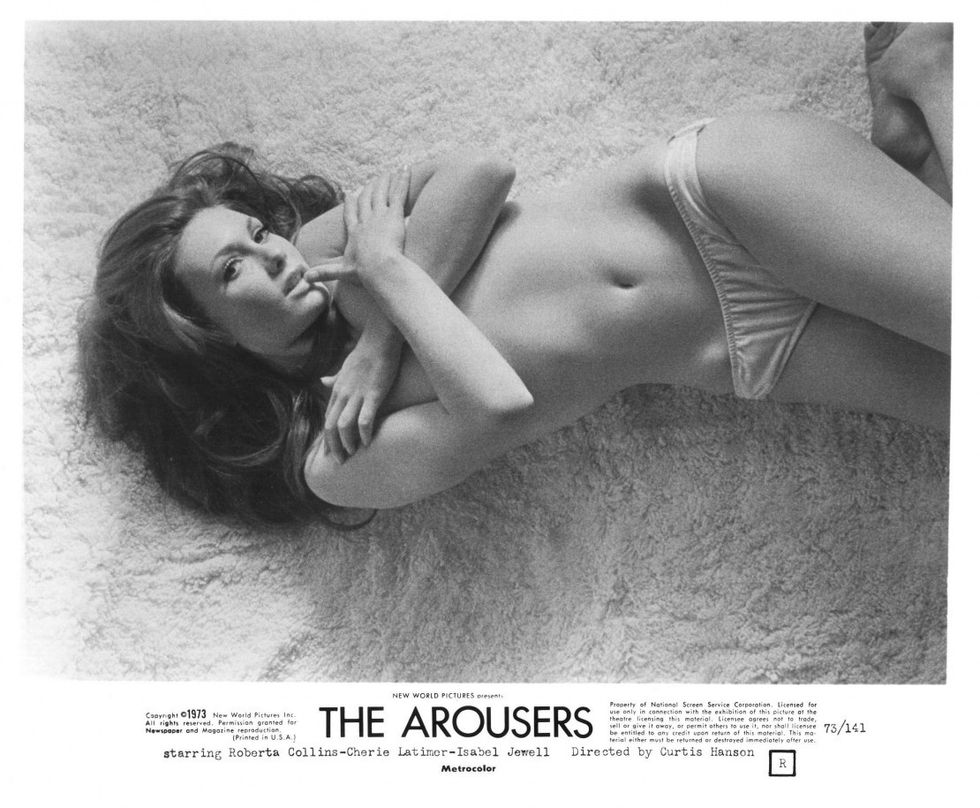

Indeed, Hanson knew a thing or two about horror movies. After dropping out of high school in the '60s, he worked as a photojournalist and editor for Cinema Magazine, an experience that brought him face-to-face with the filmmaking process. He started writing movies in his spare time, intending ultimately to direct, but knowing no one would take a chance on a self-taught kid with no credits to his name. American International Pictures got wind of the young Hanson's writing and hired him to adapt the H.P. Lovecraft story The Dunwich Horror, a production overseen by Roger Corman. Hanson made good enough with Corman to convince him to distribute his debut feature, 1972's Sweet Kill, after Corman split from AIP to form New World Pictures. The film, starring Tab Hunter as a lady killer, performed poorly at the box office; Corman had Hanson shoot additional sex scenes and retitled the film The Arousers. That didn't help much, but it did give Hanson a fair idea of what to expect from the industry: Art mattered not at all when there was money on the line. The Arousers debacle was to be only the beginning of Hanson's misadventures just south of Hollywood.

"The Arousers gave Hanson a fair idea of what to expect from the industry: Art mattered not at all when there was money on the line."

His next film, God Bless Grandma and Grandpa, a darkly comic horror thriller about the elderly using the bodies and blood of the young to live forever, was taken out of his hands when the production company, LT Films, went under. The film was sold to another producer, who handed it off to a new director. By the time the film was completed, it was called Evil Town. If you've never seen it, it's well worth tracking down— its dramatic arrhythmia is stunningly wonky and it features one of the strangest performances by a professional actor in the history of cinema, Dean Jagger. (Will Braineater tells the full story as well as anyone could.)

Hanson was undeterred by the boondoggle. He continued to write while looking for the next directing gig, eventually rebounding with the kiddie action film The Little Dragons and a script for a film that has since become something of a cult item among crime aficionados, 1978's The Silent Partner. In it, a bank teller catches wind of an upcoming heist and secures some of the loot for himself in advance. It's a classic film noir set-up and far more telling of Hanson's sensibility than the films he directed in the '70s. Hanson's directorial beginnings should serve as an object lesson to most young filmmakers: it took him nearly a decade to find his footing, but he never stopped trying. In fact, honing his writing actively helped him to become a more focused and disciplined director. The compositions and visual language of his early films all hint at someone who might later become great, but had much room to grow.

Hanson's directorial beginnings should serve as an object lesson to most young filmmakers: it took him nearly a decade to find his footing, but he never stopped trying.

Hanson kicked off the '80s by directing the film Losin' It (starring a nearly fetal Tom Cruise) and helped write the Carroll Ballard film Never Cry Wolf and Samuel Fuller's White Dog. Writing White Dog transformed Hanson, bringing him back to the classic Hollywood films he once studied at Cinema Magazine by giving him the opportunity to work with one of its luminaries. Like Hanson, Fuller worked with low budgets and came from the world of journalism. Together, on matching typewriters no less, they wrote White Dog in 18 days. It's a fierce little film—one of Fuller's last, thanks to the firestorm of controversy that greeted its release—and Hanson's movies get noticeably tighter and more dynamic following the experience of making it.

Hanson brought maturity and sturdiness to the nightmares he presided over.

Hanson this up with a series of lurid, beautiful thrillers, whose reputations may improve posthumously. The Bedroom Window, Bad Influence, The Hand That Rocks The Cradle, and The River Wild have less than auspicious reputations, but Hanson's images remain solid and intelligent, his rhythm patient and adult, and his plots a perfect mix of the absurd and the too-real. Hanson brought maturity and sturdiness to the nightmares he presided over. Thrillers today could learn a thing or two from the way Hanson used the camera to trust and his support actors as well as lend weight to his occasionally ludicrous plotting. Always displaying restraint and control, he knew that by taking his audience's intelligence for granted, they'd take the ride with him.

Every trick Hanson ever learned was put to use in L.A. Confidential, and the result is one of the few nearly perfect movies of the recent past.

L.A. Confidential is about a group of men working and dying for a corrupt ideal lorded over by a corrupt older generation. It's the same basic idea as his abandoned sophomore movie, God Bless Grandma and Grandpa: that young people will be used up by vampiric interests looking to keep themselves comfortable as the world burns. Hanson used his knowledge of horror filmmaking to fully accentuate the ugliness of masculine legacy-building and imperialism. Nothing is so innocent that it can't be defiled. Every trick Hanson ever learned was put to use in L.A. Confidential, and the result is one of the few nearly perfect movies of the recent past.

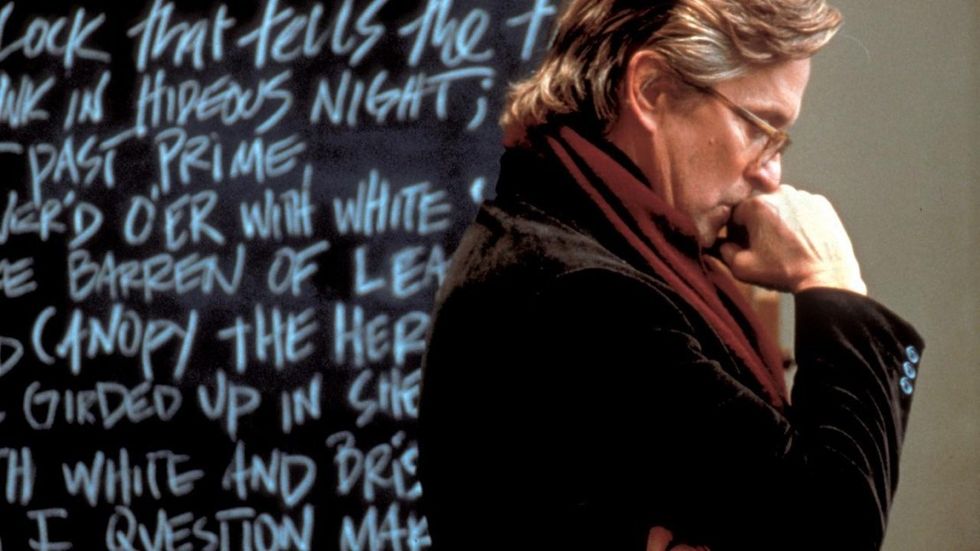

1998's Wonder Boys is a gentle inversion of the idea of old men using young men for their own gain. Adapted from Michael Chabon's novel of the same name, it follows a washed-up writer obsessed by his own legacy and captivated by the brightest kid in the creative writing class he's teaching. Scott Tobias has pointed out how magnificently Hanson evoked cities, and he may never have topped the work he does showcasing rain-soaked, blue, and broken Pittsburgh. The film is a marvelous actor's piece, with everyone from the lead, Michael Douglas, to Katie Holmes, Robert Downey Jr., Tobey Maguire, and Francis McDormand lending some of their finest, warmest, and funniest work.

Wonder Boys and L.A. Confidential prove Hanson could have directed anything on the tonal spectrum and still garner all-time great performances from his cast. He even managed to humanize the famously homophobic rapper Eminem in the underrated 8 Mile, a great Detroit movie in the way L.A. Confidential and Wonder Boys are LA and Pittsburgh movies.

He taught himself how to write scripts without having gone to film school and built a career and legacy slogging through one production system after another.

His next films, In Her Shoes and Lucky You, didn't get much love from audiences or critics, and the director slowed down. His health prevented him from finishing the mostly forgotten surfer film Chasing Mavericks; Michael Apted stepped in at the 11th hour to complete it, lending it an eerie symmetry with Hanson's early work, also altered by other hands. But the last film with Hanson's name on it is worth remembering and watching. 2011's Too Big To Fail, about the financial crisis and subsequent bailouts, is a fabulous and ferocious study of people pressed into corners looking for an escape. Claustrophobic and quick, it's got the cunning of his thrillers and the charm of his '90s landmarks.

I can't say, but I do know he deserved better. He never gave up, got better each time out, and let himself grow organically and at his own pace. He didn't allow myriad setbacks and disappointments to stop him from perfecting his art. He taught himself how to write scripts without having gone to film school and built a career and legacy slogging through one production system after another. Hanson should be a lesson to every young filmmaker who doesn't know how she'll be able to break into the business: Don't let anyone stop you from finding your voice. A high school dropout made some of the finest American movies of our lifetime. That's the American dream.

"'Back Home"via Mercedes Arutro

"'Back Home"via Mercedes Arutro 'Back Home'via Mercedes Arutro

'Back Home'via Mercedes Arutro