What Can We Learn from the 'Whiplash' and 'Black Swan' Screenplays About Telling the Same Story, Differently

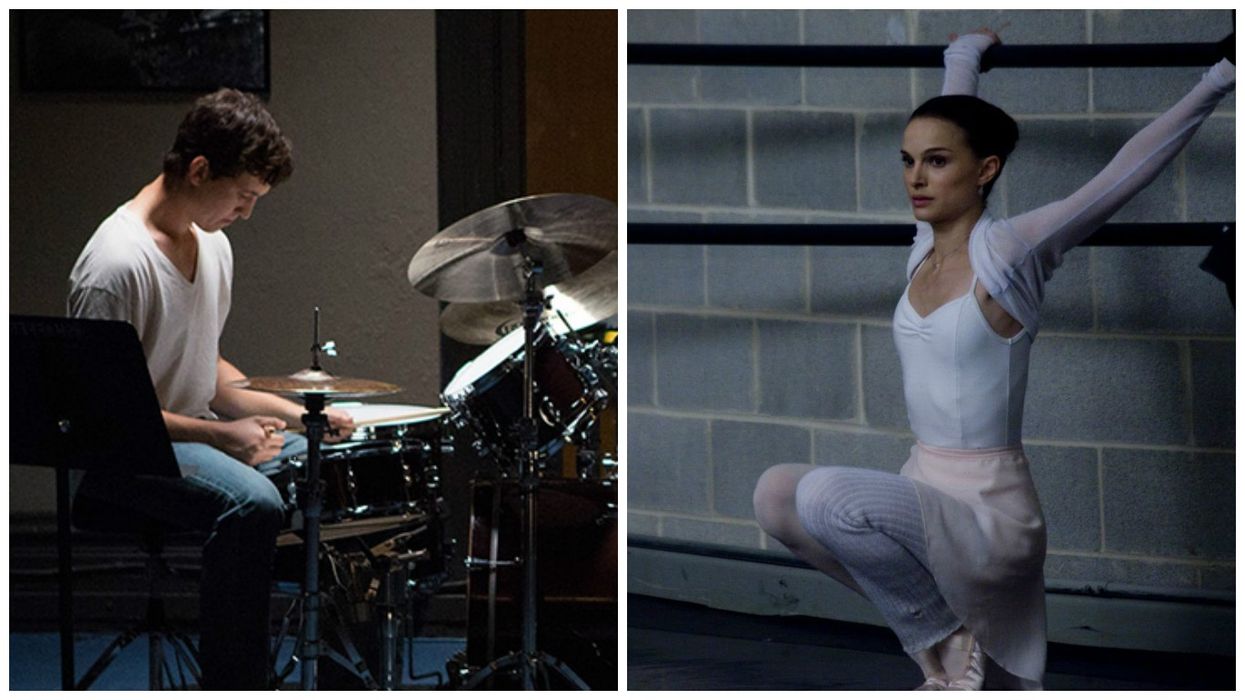

This video essay examines the structural similarities in the screenplays for Whiplash and Black Swan, two films about young artists willing to suffer for their dreams.

Lessons from the Screenplay's Michael Tucker begins his essay by noting that both movies, released within a few years of each other, "were relatively low-budget, leaned heavily on their scripts, and led to Oscar wins for great performances. But most importantly, both of these films tell the tale of an artist seeking greatness who must first endure suffering and sacrifice." The question is, how does each go about telling its story via its narrative structure, and what lessons can be learned from studying this?

Tucker goes on to explore how both Nina and Andrew's home lives are the keys to their drive. For Nina, it's a mother who is a "former ballerina...who never achieved notable career success and refuses to let Nina grow up," while for Andrew, it's a father who is "a moderately successful high school teacher and an unsuccessful writer," a man described in the screenplay as "mild-mannered, soft-spoken, average in every respect. Has the eyes of a former dreamer."

"Both of these films bring us behind the scenes of a world most people never get to see."

Ouch. Tucker explains that, in order for the audience to care about Nina and Andrew, who are both pursuing quixotic dreams, we have to identify with them, and the best way of doing this is on a primal level, by putting us in their shoes, and showing us what they fear. In the two films, "their parents represent the mediocrity they fear and will come to despise," and so, by understanding "what the protagonists are afraid of, we better understand their desires." After these opening scenes, the essay continues on, skillfully elucidating the similarities and differences between the two films. It also drives home the point that, despite their structural and archetypal similarities, each film is utterly unique. This is a challenge for every writer and filmmaker, because, really, there are only so many stories to tell, and at the end of the day (or, on the last page, or after the lights come up) the originality springs from how you tell your version of the truth.

Source: Lessons from the Screenplay