What Can You Do with 3D Sound That You Can’t Do with 2D Sound?

Technical Sound Designer Viktor Phoenix shares best practices for using audio in virtual reality.

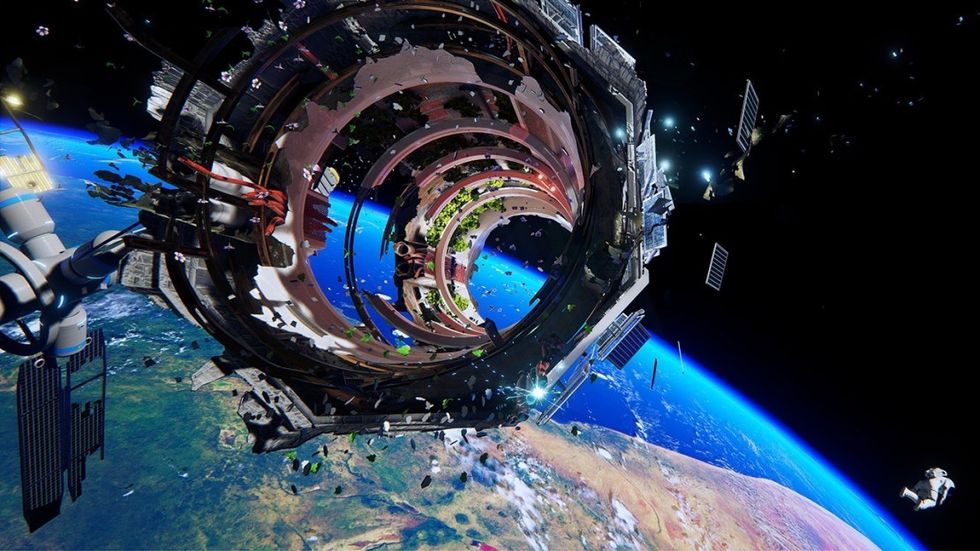

When creativity meets emerging technologies, exciting things happen. But how do filmmakers tell powerful stories in new and immersive ways? How do we take users on a narrative journey while immersing them in a VR environment where they can freely choose how to move, react, and direct their attention? A great sound team can definitely help.

Sound is a crucial tool for filmmakers to create a fully immersive environment while delivering a coherent narrative experience for the user, so No Film School sat down with The Sound Lab at Technicolor’s Senior Technical Sound Designer Viktor Phoenix to learn how to accomplish this. Phoenix, who has recently worked on Sundance New Frontiers selection Giant VR,ADR1FT, and Insurgent VR, describes the role of audio in immersive storytelling and how filmmakers can create quality experiences for the user.

"Perspective is critical to story. So the player can change their physical perspective within an experience but still keep a coherent narrative perspective through audio."

No Film School: What does a Technical Sound Designer do?

Phoenix: In a similar way that a sound mixer for film works, the Technical Sound Designer is the glue between the actual sound itself— the dialogue, the sound effects, the music—and the underlying technical infrastructure of a project. It’s not the what, it’s the how of audio—how things play, how often they play, how loud they play, all in response to user input and states of things in the VR experience, like the health of other characters, the changing environment, and things that have been said. Controlling the how allows the audio to play in a dynamic way in real time within these experiences and helps create a coherent experience for users.

NFS: What can you do with 3D sound that you can’t do with 2D sound?

Phoenix: The key difference between the two is that 3D, and interactive audio in general, is not locked. It changes based on a number of factors, like the story, what the player is doing at any given moment, and how they’re reacting within an environment. Interactive audio is dynamic; it can be changed at any time based on what the player has done and what we want them to do. With 3D audio, we recreate the way that we hear in the real world, within a virtual environment; sounds come from above, below, and behind you. It helps finalize the illusion of presence. Whereas in a film or a game with 2D sound, there is one locked-in track or one perspective. With interactive 3D audio, there are more storytelling possibilities.

"With interactive 3D audio, there are more storytelling possibilities."

For example, if a user in a VR experience is on a street running away from an explosion, we don’t get to play it back the same way every single time like you would in an action film. One user maybe decides to run away from the explosion slower, so they’re closer to the explosion and we can turn the music up a bit more and make the explosion a little more terrifying. Another user might decide to run backwards the entire time, so that changes how you’ll hear the sound and visually as well. With 3D audio, we’re allowing that audio to sound realistic within that environment regardless of where the player is in relation to that sound—above, below, behind, in front of, far away, etc. We can change the perspective as needed. Perspective is critical to story. So the player can change their physical perspective within an experience but still keep a coherent narrative perspective through audio.

NFS: Does the number of user possibilities create an exponentially larger amount of post production work?

Phoenix: We create audio rules, just like you’d create narrative rules within a script. There’s simply more opportunities, but the best approach is always one that serves the story best. We talk a lot about field of view in VR. All headsets are limited. Audio has unlimited field of view. Even if a user in an experience never moves their head, we can have sounds behind them, above them and below. We can use that sound to help guide or inform the user. For example, if somebody is taking a long time in one location because a user is awestruck (a common response to VR in new users), we can cue a sound behind them and motivate them to turn around. Or we can draw their eye to something by triggering a sound. This helps drive the artistic intent of the director in terms of creating a coherent narrative experience for the user.

"When the sound is invisible, that's when it's at its best—when it's simply part of the cohesive experience."

NFS: What should a director know during production to capture the best possible sound?

Phoenix: I'd say it's the same as with other mediums like film or games: bring the sound team in as early as possible, but not any earlier than necessary. While that might be a different point in the schedule for every project, thinking about sound earlier than you probably think you need to will always help. What’s the user’s journey? Where do they start? Where do they end up? How do we want the user to experience that journey? What is the goal? How can sound play into that journey?

I love to see the script, talk to the production sound recordists, meet with the composers—just like you would on a film. That said, talking about what you see and hear even at the script phase can be good. Recently I started working with Fountain, a markdown language developed by screenwriter John August and Stu Maschwitz, and extending it a bit to add in some 'logic' into the script. For example, you can add in, "If the player does this then this happens…" which is a bit more like writing a choose your own adventure. These details in the script phase can help achieve greater clarity of story and narrative and what the experience is supposed to be.

NFS: When do you know you’ve done your job?

Phoenix: VR is an exciting new way to tell stories. It’s looking at the history of cinema and games and then seeing how we can tell new stories in this exciting new way. But just like film or any other form of entertainment, when you don’t notice it, when you don’t think about, when you’re just deep in the virtual environment, and when the sound is invisible, that’s when it’s at its best—when it’s simply part of the cohesive experience.

NFS: What’s the future of interactive entertainment?

Phoenix: The future of interactive entertainment is procedural; entire worlds generated and modified in real-time using elements and rules that we, the storytellers define. I hear a lot of concern about not being able to control everything someone sees, hears, or does in VR and that we lose artistic control and even risk losing control over the story itself. But great stories are all about change. Our view of the world changes. It's like going back to your childhood home and thinking that the sink looks a lot lower than you remember—our perspective changes.

In the real world, sounds are changed first by the environment they travel through to reach our ears, but more importantly, by our perspective to that sound. As we tell more and more stories in this new medium and as the technology improves, we will develop a language that uses procedurally generated content more and more to build interactive narrative structures around those changes. We will discover that we actually have more ways to engage audiences—more than we've ever had. And if you're up to the challenge, there's artistic freedom in that, I believe.