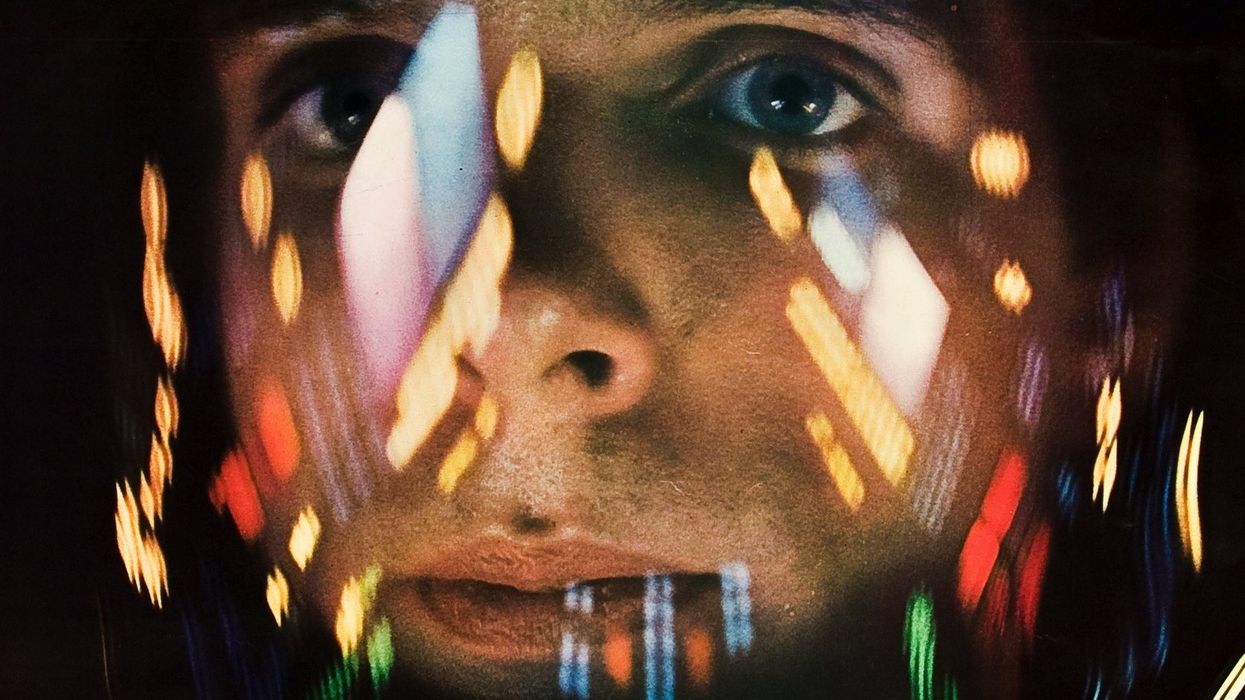

"'Back Home"via Mercedes Arutro

"'Back Home"via Mercedes Arutro

No Film School: What inspired you to create Back Home?

Mercedes Arutro: Back Home was done in the Rising Voices program, and the prompt of the contest was “The Future of Work.”

When AI started to be in the conversation and there was fear about how it would affect our creations and livelihood, I went to my favorite fairy tale as inspiration: The Little Mermaid by H.C. Anderson -a cautionary tale about losing your voice for someone (or something) that does not deserve it.

While The Little Mermaid gives up her voice to become human, Felix, the protagonist of Back Home, gives up his voice to become non-human. He licenses his voice to an AI corporation for everyone around the world to create songs with his voice. However, he's not allowed to sing live ever again. Just like in the original Little Mermaid, he loses it all. The corporation archiving his voice is as tragic as the Prince marrying someone else.

There were two things I wanted to tackle concerning AI and art. First, the dehumanization of the arts—art is what makes us humans, and the irruption of AI creates a philosophical void. Will art remain human anymore? Can AI translate the human experience? Second, who feeds, controls, and decides the reach of AI? This technology could disrupt our existence so profoundly. Are we leaving humanity in the hands of a few tech corporation owners? That feels nondemocratic to me, and that’s where I see the real risk.

Back Home is also a family story about the evolving love between a grandmother and a grandson. It shows how two very different and imperfect people can deeply love each other. I believe the antidote to dehumanization is exploring the nuances of human existence.

NFS: "Back Home" premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival– can you share what that experience was like and how audiences there responded to the film?

Arutro: It was very emotional and exciting. "Back Home" was presented at an event with nine other films. I introduced the film on stage, and I normally prefer being backstage… My heart was pounding so fast! But it was all worth it. In the end, so many people approached me and the actors to tell us how much the movie had moved them, how much they related to the Grandson- Grandma relationship, and someone even shared with me they had seen a family of four crying and hugging just after the film. How did your background in theater and wardrobe design influence the visual storytelling in Back Home, if at all?

It’s hard not to be influenced by so many years of experience. Being a costume designer is also being a little bit of a dramaturgist. You create the skin of the characters; you can trigger moods, create jokes, and, in this case, you can also invent times. This was the first time I did not design my wardrobe, but I was very present. The beautiful outfits Gigi Harding designed for the live-streaming concert scene are inspired by the world of The Little Mermaid. I wanted to leave a trace of that influence in the film. From my years in theater, I recognize Grandma’s character. She’s someone I met many times in different human forms. Those passionate, charismatic, creative human forces are committed to their ideals, sometimes so much that it can be annoying. She is such a 20th-century woman. Norma Maldonado was perfect for the role, with her charisma and spice. I was lucky to work with Paola Cortes, an amazing production designer I met working in Austin, TX, and was the first person I called when I got into Rising Voices. I knew she would understand Grandma Rose very well because she comes from working in Theater.

NFS: What was the most rewarding aspect of creating "Back Home" for you as an artist?

Arutro: "Back Home" is my first English film. As a foreigner, connecting with local audiences has been incredibly beautiful and rewarding. It is a challenge to write and direct in a second language, so I feel very proud of that achievement. I also loved that the crew was multicultural, an amazing reflection of what is living here, with people from different parts of the world and country coming together to create something beautiful.

It is also the first time I could work with a budget like this, allowing for a large crew and the opportunity to collaborate with Ludovica Isidori, an incredible DP whose work gave the film its unique look. The lighting in "Back Home" was as challenging as in a feature film, and I am deeply grateful to her for trusting me and embarking on this adventure.

NFS: What role does collaboration play in your creative process, especially with co-writers like Nico Casavecchia?

Arutro: I am, I exist, creating with others– there’s no doubt about it. Back Home, for instance, wouldn't exist without people who believed in the script and gave it all to be the film it is. I especially cherish the one with producers Stephanie O’Neill and Sara Setsuko Clausen. I’d work with them again and again.

As for Nico and I, we fell in love when we learned to live together. Eventually, we discovered we could create together, too. It's the ultimate partnership, and we made sure we protected our love with boundaries. We can write together—and even if we don't fully co-write, we always exchange notes—but we don't direct together. Border Hopper, which premiered at Sundance 2024, is a good example. When Nico directs—he's a much more accomplished director—I handle wardrobe design for his projects. When I direct, he helps immensely with VFX and design. Simply put, he's the nerdy one, and I'm the crafty one.

As a couple, we need to find balance, ensuring each has their own space, teams, and personal voice. Of course, we're aware we've influenced each other's lives after over a decade together, but we still strive to surprise each other.

NFS: Can you share any behind-the-scenes moments from the making of Back Home that were particularly memorable?

Arutro: I cherished one particular moment just after visiting the house we filmed in. We were with Stephanie O’Neill, and as soon as we were out, we looked at each other like “We found it!” It was like falling in love—we both knew that house was perfect for our location. It was early in our collaboration, and that moment made me realize she understood me, and that we would work well together. And we did!

On the other hand, once filming began, we were on an incredibly tight schedule. We filmed the short in just three days, with special make-up, wigs, and various lighting environments. Sunny California turned stormy. On the second day, it rained, and we almost had to move the concert scene indoors. Can you imagine it inside? Then, on the third day, there was an electric storm! We had to pause the shoot and change the last scene. It was supposed to be a family breakfast on the terrace with a toddler playing with the youngest Felix. If you watch the film, you'll see that didn't happen!

Thankfully, our amazing editor Alexandros Tsagamilis had footage of his son at three days old, and now I can't imagine the film without it. In the end, we made lemonade out of lemons.

'Back Home'via Mercedes Arutro

'Back Home'via Mercedes Arutro

NFS: What message do you hope "Back Home" sends to fellow artists navigating the digital age of AI?

Arutro: Be aware of the contracts. Artists will be artists and we can create new languages no matter what. But as a workforce, we need to be aware and join forces. While AI can be an amazing tool, I do think we need regulations and agreements about who manages it and what are its limits. Because not only art is at risk, we are entering a new reality— and it is not fiction.

NFS: "Back Home" is Oscar-eligible. What does this mean for you, and how does recognition of the film affect you moving forward?

Arutro: Yes, can you believe it? It’s so great! I hope this recognition helps the film to be seen by more people… at the end we make films to connect with audiences! Hopefully, it will also bring the team more opportunities to work together. I had a blast creating Back Home and I can not wait to be on set as a director again.

Fingers Crossed!

"'Back Home"via Mercedes Arutro

"'Back Home"via Mercedes Arutro 'Back Home'via Mercedes Arutro

'Back Home'via Mercedes Arutro