Learn How Robots Took Control of the Brilliant Music Video 'Automatica'

When robots rule the world, get ready for some sick music videos.

[Editor's Note: No Film School asked Shahir Daud to write up his behind-the-scenes experience directing Nigel Stanford's latest music video.]

In November 2014, Nigel Stanford launched Cymatics: Science Vs Music, an experimental music video that he and I labored on for over a year before releasing it unassumingly on YouTube. The following weeks and months were surreal as Cymatics was posted and written about by both science and filmmaking sites alike (including here on NFS) Even the likes of CNN began sharing the video.

After 13 million views and a few awards, Nigel and I scratched our heads about how we could follow it up. I pitched a few science fiction ideas I'd had on the back burner, but nothing really took. Finally, after a couple of months, Nigel uttered one word that would dominate the next three years of our lives: robots.

“What would the video look like if it were filmed by a robot?”

Yes, robots have been used in music videos before, not least the seminal All is Full of Love video for Bjork directed by Chris Cunningham. However, what made Cymatics special was the sense of authenticity to the science behind the visuals. We both knew that we would have to apply the same doctrine for this yet untitled and unwritten music video.

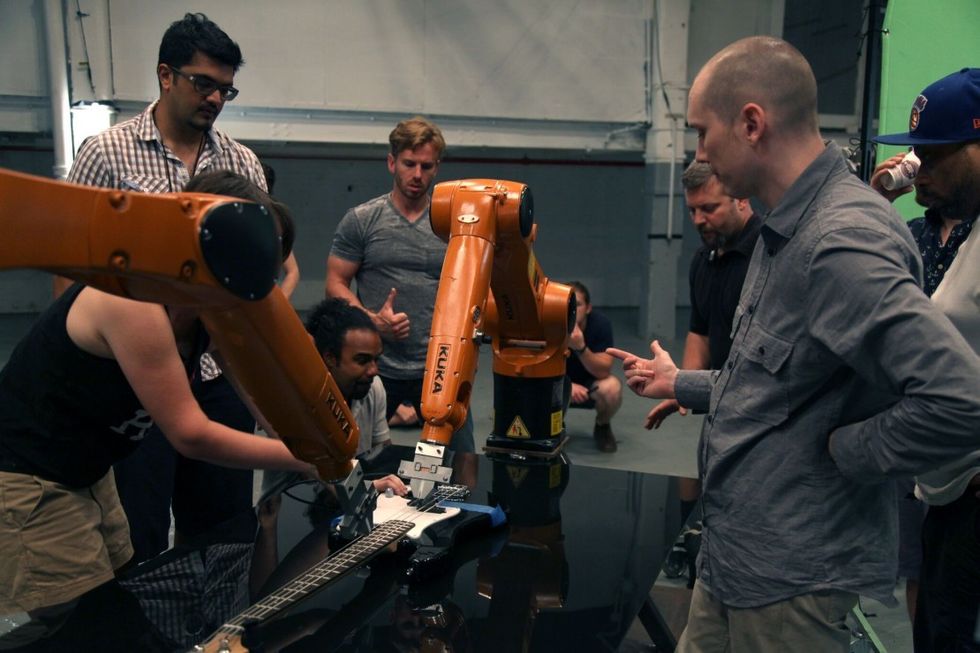

A few months later, Nigel and I were in a garage in Connecticut with three Kuka Agilus KR10 robots on loan from Kuka Robotics. Nigel had already spent a month learning how to operate the robots before I arrived on the scene. As far as a working relationship goes, Nigel is the technically-minded one who likes to figure out programming and technology, while I am more oriented toward story and structure. Both our areas of interest overlap as we try to conceptualize the video from the ground up.

With the support of Robot Animator, a plugin by Andy Robot for Autodesk Maya, Nigel was able to move the robots visually in 3D space, then have that animation translated into physical coordinates to move the Kukas in real life. As an animator myself, seeing an animation created in Maya and then rendered to a physical machine with pinpoint accuracy is quite surreal.

This is, of course, where the magic of robotics capture our imaginations. A robot is devoid of the frailty of human indecision. As humans, our search to see ourselves in our creations is the cornerstone of all endeavors, both artistic and technical. Even in these uniquely lifeless objects, our eyes light up every time they perform exactly the task requested of them. I begin to wonder if their algorithms ever wander beyond the confines of their code into the uncharted recesses of imperfection.

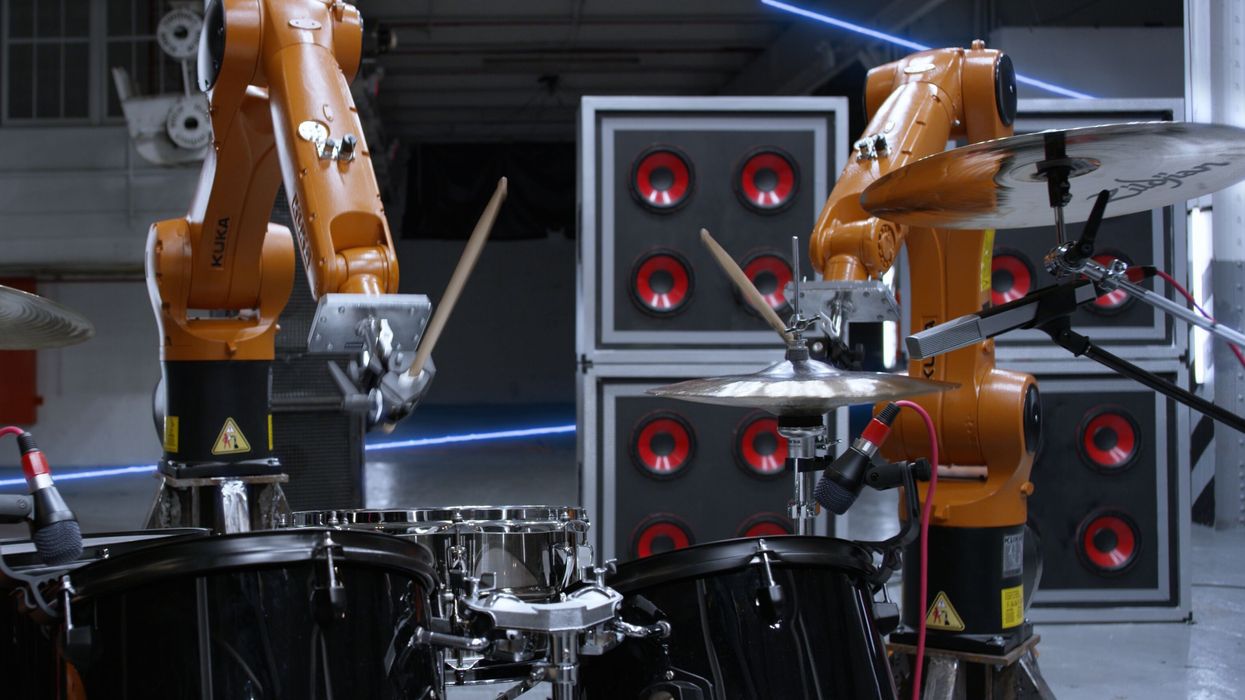

Of course, they never do, unless we make the mistake in programming, which happens a lot when non-roboticists attempt to program a robot. But through the course of investigating their programming and the appropriate movements corresponding to each instrument we had (bass guitar, keyboard, drums, turntable and an open face piano), Nigel had all the elements he needed to craft the track Automatica.

If you take a step back, we're already in unusual territory for a music video. Like Cymatics, the actual song wasn't written prior to production starting, and is so intrinsically tied to the visualization of sound, that it's difficult to actually call this a music video in the traditional sense.

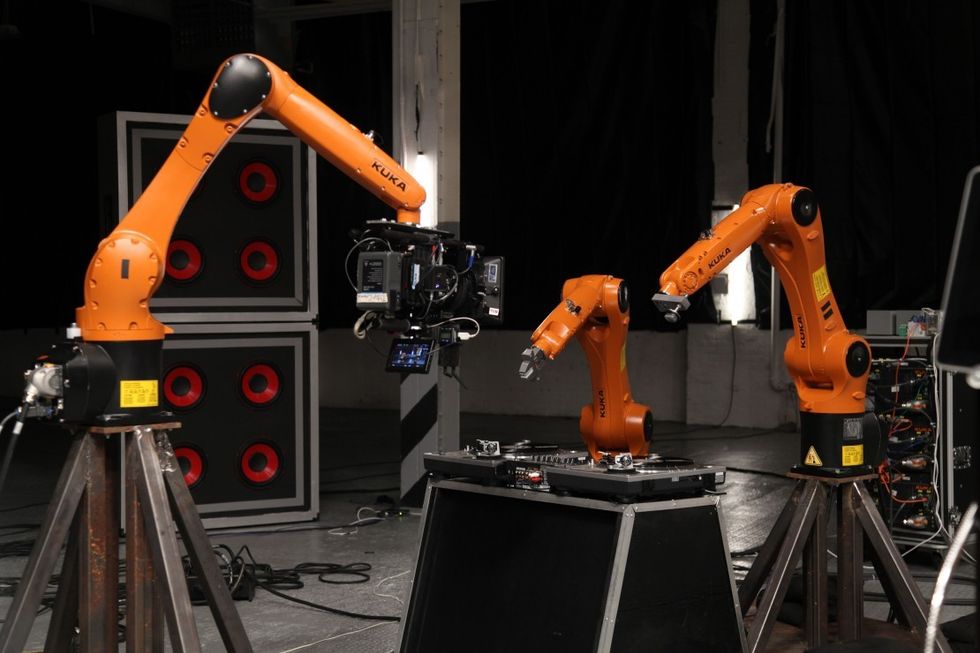

A few more months later, we were in a warehouse in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn with our production team. Headed up by our fantastic returning DP Timur Civan, the shoot took on a few additional dimensions as we brought the findings of our garage experiments into the real world. First, based on some early conceptual work, I decided that the aesthetic of the Automatica should be focused on fetishizing technology. Thematically, the video is about artificial learning and the convergence of robotics towards the singularity. To that end, I wondered, “What would the video look like if it were filmed by a robot?”

"The power distribution took a whole day in and of itself."

A robot doesn’t care for the beauty in imperfection, or the way in which a handheld shot can capture the rawness of a moment. Instead, a robot would see every moment before it happened, and move the camera exactly without hesitation.

To that end, we decided to employ motion control for three reasons. The first is that we could program robotic camera moves that no human could ever achieve. The second is that each move could be repeated perfectly, allowing us to composite our three robots into more. The final reason was safety. The Kuka KR10 is used in industrial production and is incredibly fast, however without proper anchoring can be extremely dangerous. The robots themselves have an automatic braking function to prevent any balance instability, but because we were essentially rolling them onto set and moving them around often, they couldn’t be anchored safely.

It's difficult to actually call this a music video in the traditional sense.

The Gazelle Motion Control dolly we used not only helped us get the robotic look we wanted, it also enabled us to safely counteract the instability concern of the robots. We could program a robot move in Maya at 25fps. Similarly, we could build a corresponding camera move on the Gazelle at 25fps. Then, we could step down both moves to a slower frame rate (15fps for example), then shoot the scene safely without having the robots moving in an unstable way. When the footage was imported back into the edit suite at 25fps, it would move in real time.

But here’s where the video became exponentially more complicated. What about the lighting? Timur already had a challenge in lighting an entire warehouse space with six unique spaces for each robotic instrument. Timur explains:

“We created a large overhead grid of 6 quadrants, in a cross pattern, each with four 6K spacelights on DMX control to each individual 1K light per space light. In addition, we had eight more space lights outside the cross pattern, in case we needed to add some illumination from angles other than overhead. There was no diffusion used. The sheer volume of units and their even spacing created the soft overhead industrial look. With the addition of some ground level ARRI T5 and T10’s for edge lights, we had quite the electric bill by the end. Thirty-two 6K spacelights means about 192,000W of light, just from the overheads, not counting the 30-50K of traditional heads. The power distribution took a whole day in and of itself.”

The story of Automatica also required escalation, which to me, meant that the robots were going to take over and destroy the room. If the camera was going to move precisely with repeatable camera moves that could be reset according to frame rates, then the lighting would need the same precision. Here’s how Timur handled that challenge:

“All of the spacelights were DMX controlled, and programmable to synchronize the lighting cues for when things ‘go wrong’ in the narrative. The DMX cues were programmed to be played back at any of the frame rates we needed to shoot at, so we were able to do full takes at any point, at any frame rate, and the lighting cues would match between compositing elements. This is critical to ensure a smooth compositing experience in post. Each element and layer of this project required the utmost detail. This was such a feat in post-production that the ‘fix it in post attitude’ just couldn't exist. We had to be as perfect in camera as possible. I loved the challenges we faced.”

The final result of all this automation hopefully speaks to a sense of foreboding technological anxiety, but also celebrates the beauty in automation and a sense of wonder when something achieves perfect execution. We joked on set that this video was Cymatics by way of James Cameron, a filmmaker whose work I deeply admire and obsess over when reading about his fastidious attention to detail, and his unique ability to underscore both the danger and beauty of technology in his films.

Despite being a celebration of automation, robots and the perfection of technology, no film is ever the product of pure algorithm. The artisans behind Automatica are every part the beating heart that this machine needed to live—from Timur, who gave our robots an elegantly lit world to inhabit, to Maggie Rudder, our art director, who designed their home.

Finally, this all comes back to Nigel Stanford, the artist who took a machine, gave it an instrument, and made it play one of the most striking digital symphonies ever committed to screen.