'BoJack Horseman': An Inside Look at How the Show Makes Us Cry Over an Animated Horse

In the world of cinema, there are many filmmakers who will tell you that comedy is the absolute most difficult thing you can do. Evoking a laugh from audiences is nearly impossible. Other filmmakers will claim that good drama is the toughest thing to create. After all, getting people to buy into the lives of strangers for two hours is no easy task. But what about combining the two? Apparently, you should only try if you're putting together an animated show about a world where anthropomorphic animals live alongside humans in peace.

BoJack Horseman is the story of a washed-up sitcom-star who now struggles to find his way in life as he battles through depression, anxiety, and issues of identity. It's one of television's most poignant shows, and it has the ability to make you sob in pain and laugh out loud within the smallest time frame in a way that no other show can.

One of the key reasons that BoJack is so consistently fantastic is due to the animation, which takes a bizarre world and makes it aesthetically appealing and wholly believable. One of the strongest players in the show's animation department is Anne Walker Farrell, who has served as a storyboard artist, lead animator, and starting with Season 4, took on directing duties as well. No Film School recently sat down with the director to chat about the show, broaching topics such as the differences between animation and live-action filmmaking, creating art that has a significant impact on people's lives, and advice on how to find success in the industry.

No Film School: Our site is generally very focused on live-action filmmaking, so it’s super cool to get a different perspective today talking to you about animation.

Anne Walker Farrell: I actually just had a live-action film crew shooting a pilot at my house about two weeks ago, and I had never been around live-action filmmaking before. In animation, it’s a lot about staging and mechanics—timing, weight, movement, follow-through. Watching the lighting and the camera technicalities was honestly a little foreign to me. It’s complex, and it’s crazy, and there’s a lot to learn, but it’s fascinating.

NFS: How did you first learn that you wanted to get into the animation industry?

Farrell: I always liked drawing and storytelling. I discovered anime in high school, and that was when I learned that animation and cartoons could be used to tell stories that weren’t just for kids.

"I learned that animation, much like live-action filmmaking, doesn’t require a degree to land a job. It’s all on the strength of your portfolio, the work that you do, and just being a decent human."

Out of high school, I applied to Cal Arts, which is the big animation school, and I didn’t get in. But I wanted to get down to LA and do this, so I went to a smaller school called Laguna College of Art and Design. It was a good school, but it was very removed from LA. The positive thing about that though was that you needed to be really self-motivated. I did some research and discovered you need an internship to get a job, so I just started cold calling studios, and I actually got an internship at Cartoon Network where I met a lot of cool people. That was where I learned that animation, much like live-action filmmaking, doesn’t require a degree to land a job. It’s all on the strength of your portfolio, the work that you do, and just being a decent human.

The summer before my senior year I decided that I was going to put together a portfolio and just apply to studios, and if I got a job, I’d quit school. I was fortunate, and I got work as a design assistant at a little studio called Renegade, where they were doing a show called Hi Hi Puffy AmiYumi. They offered two weeks of work, and that was enough for me. I packed up my car, and I left art school, and I moved to LA. That was my start, and most of the subsequent jobs that I’ve gotten since have been from people I met at that first gig at Renegade.

NFS: Did you get BoJack through someone that you met at Renegade?

Farrell: Prior to BoJack, I was in this kind of depressive state where I had been in the industry for ten years without really advancing my career. I had just gotten laid off, and then Mike Hollingsworth, the supervising director on BoJack, who I had worked with at Renegade, sent me a Facebook message of all things asking me if I wanted to come on for a couple of weeks as a board revisionist on this new show.

"My jaw was on the floor, and I realized, 'Oh man, this is not what I thought it was at all. This is going to be really cool.'"

I thought it might be cool, so I fell in, and I start watching the animatics, which are the first stage in animation. They’re almost like a comic book on film, and it gives you a sense of the animation’s timing and the story. The show takes a couple of episodes to get going, but I distinctly remember watching the montage at the end of Episode 4 [of Season 1], where Wade, Diane’s ex-boyfriend, is telling her, ‘You think that you’re happy and great, but you’re a piece of shit like the rest of us.’ It’s this really dark speech, and my jaw was on the floor, and I realized, ‘Oh man, this is not what I thought it was at all. This is going to be really cool.’

NFS: You ended up being a lead animator on that first season, right?

Farrell: Yeah. Our production has two phases. There’s pre-production, where we’re building the look of the show with storyboards and design, then we send it overseas to be animated at Big Star Studios in Korea, and then it comes back, and we do revisions on the animation. For Seasons 1 and 2, I was a storyboard artist for the first half and lead animator for the back half. Then on Season 3, Mike brought me on as an assistant director for my mentor Amy Winfrey in the first half, and in the back half, I was the lead animator.

This past season, I was a director, which included being storyboard director for the first half, and animation director for the back half, all of which I did in tandem with my friend Aaron Long. It’s basically two different roles, depending on the stage of production.

NFS: Could you walk us through your directing process on an episode?

Farrell: Directing for animation is very technical and very methodical. You do a lot of planning on the front end, but you have a lot of time to do it in.

I have a team of about three to four people underneath me, including an assistant director, a couple of storyboard artists, and a revisionist. We get a script from the writers, and we’ll all talk through it, and come up with ideas for occasions to add jokes. For example, if the script says, ‘Todd is having a phone conversation,’ but it doesn’t say where Todd is or what he’s doing, then we might try to put him in a funny place to plus things.

"When you’re the director, you’re leading, it’s your call, but you hire these people for a reason. Trust them to do their job and come up with cool shit you wouldn’t think of."

NFS: You guys are coming up with a lot of those background jokes then?

Farrell: Oh yeah, that’s us. The writers will put stuff in, but a lot of it is us. Mike is big about adding in a lot of the BoJack animal puns in the background.

That collaboration is something that I love about BoJack. One of the important things about any production is collaboration, and when you’re the director, you’re leading, it’s your call, but you hire these people for a reason. Trust them to do their job and come up with cool shit you wouldn’t think of. That was one of my best lessons I took away from working with Amy. She runs the ship, and you don’t forget it, but she’s a master of bringing the team together to create something really good.

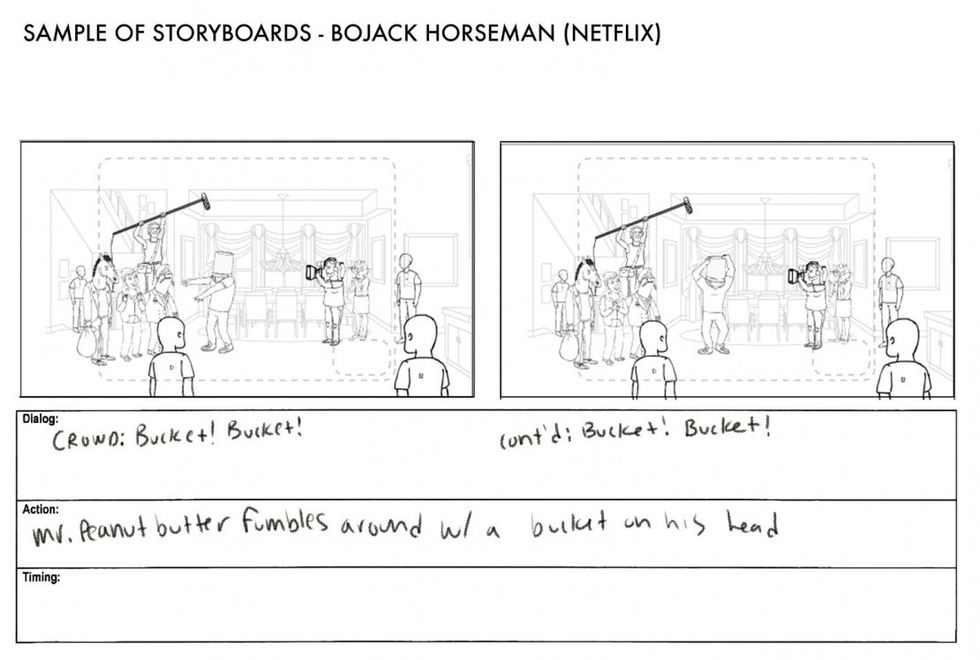

NFS: When you storyboard, do you use pencil and paper?

Farrell: No, actually, we work all digital. We do everything in Flash, on what’s called a Cintiq, which is like a computer monitor that you can draw on with a stylus, so it is hand-drawn. The animate button is a myth, and may it stay a myth because otherwise, I’ll be out of a job.

NFS: So what comes after that first table read?

Farrell: We’ll usually do a week for what’s called a thumbnail pass, which is just one or two rough drawings showing where characters are and how they move around the stage. If BoJack is emoting, we need to indicate every single pose he takes and when he takes it. You can’t do too many poses because then the character just looks like they’re flailing wildly, but if you do too few, they look dead. You have to find this happy medium of how many drawings and how much detail is enough.

That goes through an approval pass, and we’ll do a couple of small revisions, then we'll put that all together and ship that out to Korea. They animate it in a couple of weeks and then it comes back to Aaron and me.

"The entire process start to finish takes about nine months for one episode. It’s like a baby."

We get a week per episode at this stage, and at this point, it’s technical changes like fixing a head turn or body turn that doesn’t have a lot of weight to it. There are little things you do when you move, like when you get up out of a chair, your body compresses a little bit, and your head hangs lower when you get up. If you have a character who just gets up out of a chair without their head and shoulders moving, it looks really wooden.

After addressing those notes, the episode goes through compositing, which is where we’re adding lighting and effects in After Effects. That’s one of the reasons I think the show looks so good. The textures in our designs and the After Effects process give it all a really cool, polished look.

Then it goes through our final editorial pass, and it's off to Netflix. The entire process start to finish takes about nine months for one episode. It’s like a baby.

NFS: One of the big emotional cruxes of the season is in Episode 6 this season when you have BoJack tossing the doll off the cliff, and the physicality of his character is a big part of selling that moment to us. How do you approach creating so much emotion in a character who appears so silly at first glance?

Farrell: That sequence was storyboarded by one of our board artists, Yair Gordon, who is awesome. We had been in this inner monologue in BoJack’s head for most of the episode, and we’re getting to this point where he’s boiling over, and he just loses touch with reality. He’s in this tantrum, and we wanted to make the viewer feel like they’re in it with him, so we cut around a little weird with some jarring camera moves. We’re not only in BoJack’s head in the midst of this mental tantrum, but we’re also with Hollyhock, and with Mom, who has no idea what’s going on. Then he hurls the doll over the side, and we end in this wide shot where we have a moment of stillness right after that screaming rage fest baby hurling, and BoJack’s like ‘oh goddamnit’ and we realize we’re back to reality.

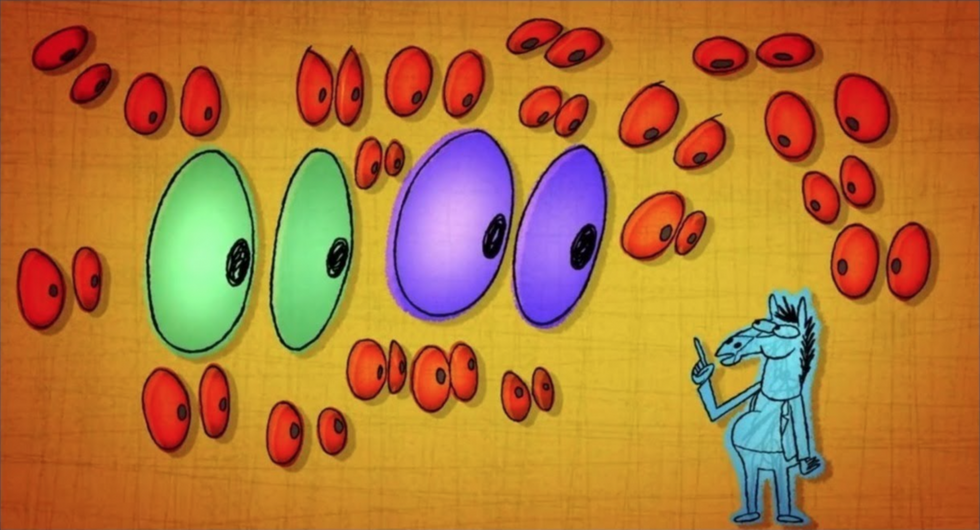

NFS: How did you come up with the visuals for the internalization of BoJack’s depression?

Farrell: It was me, my assistant director Otto Murga, and production designer Lisa Hanawalt who came up with the look. Otto and I wanted to do something like a crappy UPA cheap cartoon from the 60s, where it’s a little ugly-looking. Lisa did some fantastic stream of consciousness stuff where she just does not give a damn, and it is delightful. Otto and I boarded the sequences with the help of her visual design, and you’re looking at these drawings, and it evokes an emotional response where you’re laughing, but you’re also thinking, ‘Oh god, it’s so real.’ We wanted to do a marriage of those two feelings.

It’s one thing to draw and to make cartoons, but I get an enormous amount of joy and personal satisfaction from hearing people react to the art that I make and the stories that I help put in the world, and this episode has gotten so many positive reactions. I’ve seen people decide they should get help after seeing what goes through BoJack’s head, and then people online will respond with such positive support. It’s phenomenal. I’ve never experienced anything like that before, and I’m so proud of us. We done good with the sad horse.

"It was therapeutic to draw. I remember boarding it just thinking, 'Fuck you!'"

NFS: It’s really a fantastic episode. Would you say that’s your favorite of the three episodes you directed?

Farrell: Yeah. I love all of my children equally, but I especially have a place in my heart for the very end of that episode. We wanted to push the final sequence in BoJack’s head, so I decided to take a stab at it and push the craziness further. At the time, it was two weeks after the election, and I was not happy at all. I’ve always struggled with depression, and that was one of the first times where I was finding myself unable to fight through it. I was home sick, and I was in my office with this sequence, and it was like I was vomiting drawings on the page. It was therapeutic to draw. I remember boarding it just thinking, 'Fuck you!'

Then the final sequence of that episode, after this crazy, frenetic last bit in BoJack’s head, is out on the patio, and it’s just silent. BoJack and Hollyhock are having this conversation, and then that music comes back in, and it’s a song throughout the episode that has been an audio cue telling you that all is not well. We see BoJack lie to her about the voice because he loves her and then we cut to black. I was so, so happy with the way that came out.

NFS: The lighting of that scene, with the pool acting as a source, was something that really subtly enhanced the tone as well.

Farrell: Yeah, and that goes back to comp. I really think comp gives our show an edge. It’s a lot of subtle stuff that you almost overlook. It adds to the show in a way that if it’s gone, you instantly notice, but if it's there and it's done right, you don’t see it.

NFS: In Episode 2 this season, we see these two timelines colliding, and we're treated to some really cool imagery. How did you come up with the way that you wanted to visually intertwine those two stories?

Farrell: The show creator, Raphael Bob-Waksberg, gave me a comic called Here by Richard McGuire, which takes place in a house over millions of years. It cuts through time with this technique where you’ll see the house in 1910, and through a window in the corner you’ll see just a peak of what it looks like in 10,000 BC. I thought it was really cool, but I wasn’t thrilled about the windows, so I watched Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind for reference on how to treat two realities crashing into each other. I wanted to do something a little bit dreamlike and strange, but not jarring, and I think we came to a happy medium.

Julianne Martin, our comp supervisor, was a big part of devising the look, where it’s not a window, but more like a blurry edge around each reality. Julianne helped with the color scheme, pushing the saturation way down on BoJack’s reality and pushing it up in the 40s. And as we push forward in the episode, BoJack’s tonal treatment is a little bit brighter as he gets toward his resolution, whereas the 40s get a little bit dingier and washed out as we come to Honey’s unfortunate conclusion.

"Work hard and be kind."

NFS: One of your other divergences from the traditional sitcom style is in Episode 10 with the clown-dentists breaking Princess Carolyn into the studio lot.

Farrell: Clownstravaganza, as it was known among the board artists. That was a fun one. Again, that was Yair. We started with something different and then Mike actually brought up the split-screens idea. That scene is BoJack’s aesthetic cartoonishness at its finest, where you’ve got 15,000 absurd things happening at once that all culminate in Princess Carolyn dropping into a meeting blind-drunk. It was fun being able to add in little background gags and stuff, like at one point Todd is yelling from a tree and the clown who carried him is unconscious, and all the balloons are shot. Something happened and we don’t know what, but we’re just going to keep going. That sequence was a beast and a half, but it was a blast.

NFS: If you could give one piece of advice to someone who is aspiring to get into the animation industry, what would you want to offer to them?

Farrell: It’s actually two, but it’s as simple as work hard and be kind. You are the one who’s going to be motivating you. Nobody else is going to tell you to get things done. We all help each other out when we can, but when it comes down to it, you’ve got to make it happen. And be kind. Every job I’ve ever had, including BoJack, came from my first gig. People remember when you’re kind and willing to learn, and even if you’re not the best in the room, that’ll carry you far.

And if I can squeeze in one more thing, I had a teacher in college, Marshall Vandruff, who said you can be the best artist in the room, you can turn in all your work on time, and everyone can like you. As long as you are two out of those three things at any given point, you will always have a job.

"'Back Home"via Mercedes Arutro

"'Back Home"via Mercedes Arutro 'Back Home'via Mercedes Arutro

'Back Home'via Mercedes Arutro