Why You Should Get Involved With Your Colorist as Soon as Possible

From Film Independent’s Project Involve to Short Film Special Jury Award at Sundance, 'Emergency' cinematographer Jomo Fray shares his insights on the artistic process.

Jomo Fray is a cinematographer on the rise. His work has been featured at such festivals as Cannes, Rotterdam, and Tribeca. His most recent work, the short film Emergency, which was part of Film Independent’s Project Involve, just won the Short Film Special Jury Award at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival.

In our interview, Jomo shares insights into how cinematographers can benefit from similar opportunities, his artistic process, thoughts on Vimeo and Instagram, working with EFILM and the importance of having a great colorist, and advice for those just starting it out.

No Film School: Emergency got its start through Film Independent’s Project Involve. Could you describe how it might benefit an up-and-coming cinematographer?

Jomo Fray: Project Involve was such an incredible experience. The program selects 30 up-and-coming professional filmmakers from underrepresented communities and helps to integrate them into the larger film ecosystem. Not only did they expose me to a set of incredibly talented filmmakers, they put me in the room with many of my heroes/heroines and gave us space to have real and intimate conversations. One of the best things about the program is their focus on mentorship. Through my involvement in the program, I was connected with Chayse Irvin, CSC. Learning from him has been one of the most fruitful experiences of my career. It is hard to even begin to quantify all that he has taught me, but his constant guidance and support for me and my work have helped transform my process. I truly can’t overstate the impact Project Involve has had on my career and thinking.

NFS: How did you become the cinematographer of Emergency?

Fray: Carey Williams, the director, approached me with the script saying that he wanted to visualize the story in a totally different way. The script was about three men of color who return home and find themselves thrown into a compromising situation. In telling this story, we wanted to veer away from any and every expected choice in how this story might be shot and find something special together. That excited me! One common choice in shooting some of the tenser scenes in the film would have been to rely on handheld camera motion to translate the visceral quality and immediacy of the moment. In reaction to that, we choose to have the camera always locked off or on a dolly in those moments. The challenge then became how we could still imbue the image and the moment with a similar visceral quality without the use of handheld. Those were some of the most exciting moments for me to shoot. We were both able to push ourselves to think about our tools in a different way, and in so doing try and find our own distinct cinematic grammar for the film.

NFS: What were your artistic goals on Emergency and how did you realize them?

Fray: For me, creating a visual language for a piece is so borne out of the emotions in the script. I love sitting with a director and doing a deep analysis of the film together—really talking about the characters, the story, the emotions, and what they hope to evoke or give voice to with the film. It is out of these conversations that a visual language and look organically begin to emerge. In many ways, I feel like being a cinematographer is a lot like being a translator. We take the moods, tones, and emotions from a director and help translate/transmute them into lenses, focal lengths, lighting units, camera movements, etc.

"I like to speak in emotions and images with a colorist—this is what I want to feel in this scene, how do you think we can expand on that?"

For Emergency, we wanted to create a delicate image—one that was on the edge of falling in upon itself at any moment. The reality of the story is tenuous—we wanted to create an image that matched that uncertainty. We also wanted to push the digital image. I love shooting on film, but for this project, I wanted the type of grain and texture you get from an electronic sensor. I wanted to see into the dark and feel the camera straining to do so as well. Towards that goal, we shot at high ISOs and underexposed the image by at least four stops. To get the look we were after involved shooting a lot of camera tests beforehand and bringing them to colorist Jason Hanel at EFILM to help build the look.

NFS: What camera did you shoot on and could you describe your approach to lighting?

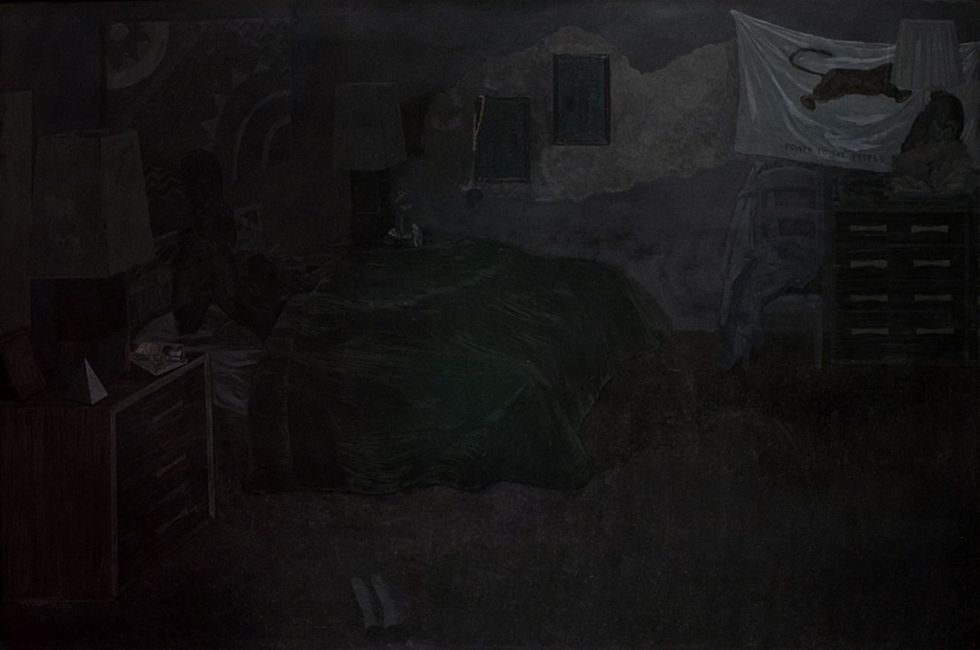

Fray: We shot the film on the ARRI AMIRA and a set of Leica Summilux-Cs from The Camera Division. In terms of the lighting strategy, we wanted to go dark and rely primarily on artificial lighting sources (Kinos, LEDs, and augmented practicals). For this piece, I was more interested in lighting spaces and creating opportunities for the actors to dip in and out of the light. Marginality and playing within those lines is a major theme of the film and I was really interested in the texture these moments between light and dark gave us. A reference that was always on my mind was Kerry James Marshall’s Black Painting. In the painting, he only uses different shades of the color black. To see it in person is particularly special, you just stand there straining to make out an image until it slowly starts to take shape. I was interested in trying to bring that experience to the moving image in this film.

NFS: Describe your approach to the final look and working with colorist Jason Hanel at EFILM?

Fray: I love to get a colorist in early. After a director and I have started to drift towards a general direction for the aesthetic, I like to write it all down and create a visual treatment of sorts. At that point, I usually send it to the colorist not as a codified thing, but as a starting point. I love getting their creative input and thoughts on the film as early as possible. I like to speak in emotions and images with a colorist—this is what I want to feel in this scene, how do you think we can expand on that? It’s an incredibly collaborative experience and one in which I want their artistry to have space to play and react to the work.

In terms of our work on Emergency, Jason Hanel was a key collaborator on the project. The delicacy of the image was so razor thin at times that we could not have realized the vision of the film without his expertise and artistry. We wanted to create a degraded digital image that still felt understated. I also did not want to add grain in post but have it created from the sensor which certainly made things harder, but Jason was in on the project early and was quintessential in building the look of the film and taking us from pre-production out to post.

"Cultivate an open heart and technique will follow."

NFS: You have a website and Vimeo account. What role does your online presence have in building collaborations and securing work?

Fray: I think every platform—be it your website, Vimeo, Instagram, etc.—is an opportunity for the expression of your aesthetics and values. As filmmakers, we each have our own unique perspectives and these different modes of online expression all work as an extension of that perspective and thus an opportunity to share that perspective with others. If I’m not on set, I’m always online watching new work and searching for new interesting directors.

NFS: Any advice for a cinematographer starting out?

Fray: In terms of any advice I may have for a cinematographer starting out, I would encourage them to shoot from the heart. A large turning point in my style and approach happened during my time in film school. A piece of work I had done had received a particularly harsh critique from a mentor for its focus on technique. I think the critique cut so deep at the time because it felt as if it was not only a commentary on my filmmaking, but a call for me to be more open as an artist. The experience pushed me to think deeper about image making—to push past merely trying to capture an event or a moment from the script, and truly search the depth of what the director and I were trying to express and give visual life to. There is an importance to technique and honing that, but I think there is a limit to what it can achieve on its own—it is important in and so far as your ability to let it go and be fully present on set with an open heart. Although I have far from mastered this mode of shooting, I think it is a road worth traveling. Cultivate an open heart and technique will follow.

This interview was done through EFILM Hollywood, which is a partner in Film Independent’s Project Involve. Follow EFILM on Twitter / Facebook / Instagram.

For more, see our ongoing list of coverage of the 2018 Sundance Film Festival.