How to Make a Documentary About a Subject You're Close To: Steve Loveridge on 'Matangi / Maya / M.I.A.'

A different, private side to a very public performer.

Winner of the World Cinema Documentary Special Jury Award at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival, Steve Loveridge's Matangi / Maya / M.I.A. is an archival documentary where some of the footage was shot and provided by the subject herself.

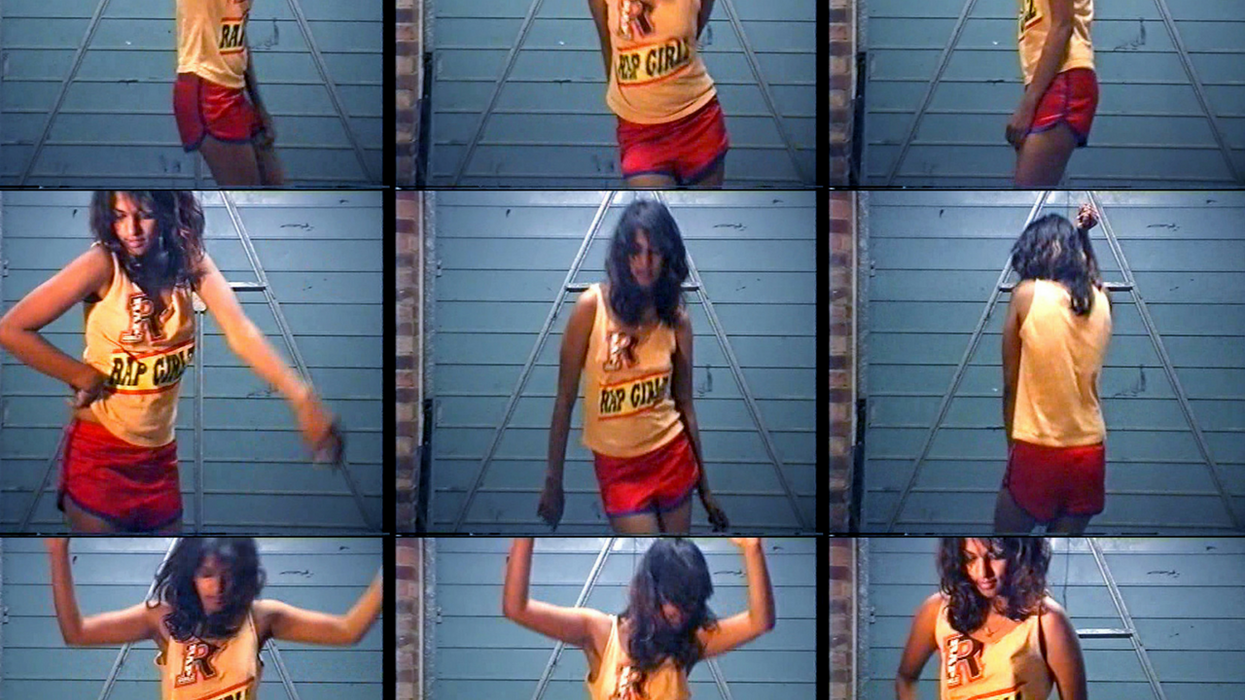

M.I.A., the popular rapper who hit peak popularity in 2008 with the hit single Paper Planes and has gone on to become a celebrated Grammy and Academy Award nominee, is the subject of Loveridge (a friend since college)'s documentary about the popular performer, and her own performative material provides the backbone for this moving feature. Her real name being Mathangi "Maya" Arulpragasam, the documentary seeks to show both the private and public lives of Maya, as told both by herself and, as the film progresses, through the perceptive eyes of the media that seek to condemn and tame her. When she recieves negative pushback from the NFL about displaying the middle finger during a Super Bowl halftime performance, the true scope of her influence (and impact on those who will proceed her) is truly felt.

As the film is currently playing in theaters around the world, No Film School spoke with Loveridge about his friendship with Maya, the amount of personal footage he had to work through, why he had to have final cut, and what he learned his first time out as a feature film director.

No Film School: Could you speak a little about your background in the digital arts and how you came around to pursuing filmmaking?

Steve Loveridge: I was always massively into film as a kid and then I went to an art school, called Central St. Martins in London in 1995, to study film and video as fine art. It was a very experimental kind of arts-based film course, making abstract and experimental filmmaking, installations, lots of short films, etc. We really didn't study any kind of fictional narratives that were playing in the cinema or anything like that. I met Maya on that course though.

After that, I specialized in animation. I was always good at drawing and gravitated towards that while I was at film school. My graduate films were 16mm experimental things that had to do with gender and sexuality. Afterward, I won a competition, an animation competition, doing traditional hand-drawn, 2D pencil animation. I made a little short film for Channel 4 in the UK.

After that, Maya got her record deal, and I started working on her visuals and websites and record covers and all that sort of stuff, and carried that on. But every time she wasn't making an album, I went back into animation and graphics and worked doing that. I ended up doing computer games and learning 3D animation in between the albums, and I worked on Grand Theft Auto and stuff like that, making these little people...

It's kind of like a very mixed up career, but all visual in one way or another.

"My life was changed by TV shows and music videos and reading magazines, and that's what made me want to go to London and gave me the confidence to come out and be a gay kid."

NFS: How did your friendship with Maya develop? What did you find in common?

Loveridge: I think because I was the gay kid making films about coming out when you live in suburbia and you don't know anyone and she was the minority brown face, we both clicked and had a shared appreciation of pop culture, or what it could do for you and how important it was.

The course we took looked down on pop culture as if it were trivial and unimportant. It didn't really get talking about it in the theoretical side of things and I think we found the fine art side of things really elitist, impenetrable, and we just couldn't imagine ourselves ever genuinely going out and getting jobs or paid employment in the world of fine art, and that's what we had been training in. However, we did know how to do that with pop culture and we did have a passion for that that ran really deep.

My life was changed by TV shows and music videos and reading magazines, and that's what made me want to go to London and gave me the confidence to come out and be a gay kid. When I looked through the tapes that Maya gave me to make this documentary, some of them were just VHS tapes of the things she had recorded on TV when she was a teenager that showed South Asian representation. Anytime there was a film star, or a pop star that was Indian or Tamil, she was recording it and feeding off that, because you need it when you start off with anybody you know is not the same as you. I think that's what led us to thinking of pop culture as important and valid and worthwhile.

NFS: How much archival footage shot by Maya did you have to work with? How did you navigate through it all?

Loveridge: It was 700 hours of verite stuff, but it was really, really intense because she was an amateur or student documentary major. It's not 700 hours of random home movies of birthday parties and just the general stuff that everybody has. It was 700 hours of her trying to make films and unfinished documentaries.

It was a full documentary that was unedited, like the trip to Sri Lanka that was hours and hours of stuff in Tamil that had to be translated to even understand it. And then all of the films that she had made while a student, interviewing her family and investigating their past history. There were tons of options for the threads I could've picked up, and actually, the quality of filmmaking, or the quality of footage and coverage, actually falls off when she becomes famous.

It's a weird reversal of every other filmmaker, every other kind of bio doc. Traditionally, after the person gets famous, that's when all the good stuff happens, but Maya turned the camera off and stopped filming herself. She didn't need to anymore because people were listening and were asking her about her story. Journalists were doing the documenting and the recording for her. That's why my film then switches over to archival. There were about 100 hours of archival stuff of her being interviewed in various ways and about 100 hours of her on tour performing, of people who professionally filmed the gigs in one way or another. So all in all, nearly 1000 hours.

As a filmmaker, you sit down in an edit suite and you just have to watch [it all]. Put in tape number one and press play, and that was it for four months or something. There was no way to shorthand it and sketch over things, because her story is so complicated. I wasn't going on there with an agenda of like, "Oh, I need to find this bit that says that, and this bit that says this." I actually just came in with a blank sheet and went, "Let's see what we've got to work with first," because, being her friend, I already knew the story and I wanted to go a bit deeper with it, finding interesting things that weren't the surface telling of it. I really just had to watch it very thoroughly.

"Because Maya is still alive and in mid-career, you couldn't do that kind of mythmaking. Legend-building wouldn't have worked with this."

NFS: When working with archival material, how important is establishing a narrative structure? How overwhelming does it get in the edit?

Loveridge: I was thinking of an overall thematic arc more than a narrative structure. I think I wanted to leave the narrative really loose and open, and make a film where I wasn't being too didactic in telling the audience like, "Here's the bad person. Here's the good person. Here's the obstacles, and this is the instigating incident," and that kind of reactive storytelling that you're supposed to do, because I just couldn't do it.

While I was making the film, the Amy documentary from Asif Kapadia came out. He does that thing so well, taking real life and turning it into a classic Hollywood narrative with all of the beats in the right place, and his filmmaking feels so seamless. But with this stuff, because Maya is still alive and in mid-career, you couldn't do that kind of mythmaking. Legend-building wouldn't have worked with this.

I knew most of the people in her footage and had been there at the time, and when you take people and turn them into these roles of like, "You're the bad one," or "You're the obstacle," or "You're the one that did wrong by her hero," I felt that it needed to be more complicated than that. I couldn't just go, "Well, he's shit. He's the patriarch. He's a white guy. He's blonde and blue eyed", and like, "He did everything," or "He betrayed her," because I was there at the time. It was more nuanced and complicated than that, what went on in their relationship. Even though that whole story thread fell by the wayside, even if I had depicted it, I couldn't have done a very simplistic retelling of it.

"It wasn't so much that I was sensitive to her, but I was sensitive to the politics of the situation, the family, and their concerns about having a film made, how much emotion it was gonna drag up of past history that had previously been put to bed."

NFS: Being a documentary filmmaker, does knowing your subject personally provide benefits or limitations?

Loveridge: I think knowing her meant that I had knowledge and access that no other filmmaker would've got. I really had an understanding of where she was coming from that other filmmakers, I don't think, would've been able to bring to the table. You do, however, compromise your objectivity.

It wasn't so much that I was sensitive to her, but I was sensitive to the politics of the situation, the family, and their concerns about having a film made, how much emotion it was gonna drag up of past history that had previously been put to bed. To the viewer, it might seem like nothing, but to the Tamil community dealing with those issues, anytime you speak out against the Sri Lankan government, it's a fearful thing to do, you know?

They were genuinely worried, like, "Don't shine a light on the family in a bad way that would put our relatives in Sri Lanka in danger or anything." There was that responsibility as well. I think on the whole, Maya did a really good job of being trusting. I mean, ultimately, she did hand over hundreds of tapes of stuff and she didn't watch them herself before she gave them to me. She then signed a contract that said I had final cut and she was great about that.

But then throughout the process, even though I said, "You're never allowed in the editing suite, or anything," I occasionally had to ring her up and go, "I don't understand who this person is, or what's going on in this tape," or, "Well, tell me how it felt when this thing happened." There was a little bit of interaction but I couldn't have her watching the footage, because, you know, like everybody, you're natural instinct is to go, "Don't use that shot, I look really fat," or, "Don't use this, I'm saying something stupid."

I had to draw a line and be quite strict that Maya couldn't interact in that kind of way. However, it was very useful having a relationship with her that I could clear out any of my own doubts about what I was actually watching and what was going on. It was great having someone you knew that you could ring up and ask, "Hey, what's this uncle's job, and what's he talking about in this clip? I don't understand."On that level, it was great.

NFS: Was there a lot of stop-and-start regarding production? When did you know you had a feature?

Loveridge: It was always intended to be a feature, and I always had a vision of it sitting next to Exit Through The Gift Shop, or something like that. That was how I pitched it to people when I was first trying to raise the money. I was like, "I want a proper documentary that goes in cinema and is on DVD on a shelf that people can buy, and is considered a real film. What I don't want is a kind of VH1 Behind The Music-y sort of thing," which is how it really started off.

When Interscope was funding it, Maya's management lined me up with loads of celebrity "talking head" interviews to film and I did it because I thought they might ultimately come in handy, even though I didn't want to make that style of film. However, that all ended up just going in the bin really because the funding completely changed hands and Interscope stopped funding it very suddenly with no warning. The project was put to bed for about a year, and then I approached some UK funders and somehow we found Cinereach. I had a bit of a fight with Maya's management and leaked a little trailer that I had made and I said, "I'd rather die than work on this," and I got really dramatic on Twitter!

That was actually quite fortuitous, because not only did Cinereach, the ultimate funders, see that trailer and ring me up and go, "Can we help?" but they turned out to be the perfect partner. It also meant that there was a very clear divide between the film that Interscope had funded and the new project. It drew a line and it meant that we were very clear on who owned the rights to what footage and who was signing off on what. It was just like, "Your film's finished. We didn't make it. It's put in the bin. I'm not gonna use any of that stuff, and let's start all over again." When everybody says the film took seven or eight years, it didn't really.

This version of the film really started in 2014. It was just that, from being a first time filmmaker and going into the situation quite naively, I didn't know how to find the right team and bring it to the right people, or I didn't have the confidence that they would be interested. It took a couple of false starts for me to find a funder that was like, "Oh, we understand exactly what you're trying to do, and we've got the money. Come to us."

NFS: What resources did Cinereach provide?

Loveridge: They've partnered it up with just awesome people and they're very interested in getting it to audiences that would find it difficult to see this film in organized screenings. We've just been to a high school today, to show it in Edison, New Jersey, that has a large Tamil student body.

It was great for Maya to see teenagers reacting to the film, hearing their feedback and their own family stories. That's what it's all about. Cinereach has also helped me as a first time filmmaker, to negotiate the deal-doing and distribution stuff that's very arcane and mysterious to me, or it was. THey partnered us up with Dogwoof from the UK and that's done a fantastic job. We just did the London theatrical premiere last week and that went really well.

I was really taken aback at how well it went. Cinereach is a really good company. I'd recommend to anyone whose got a project to give Cinereach a call. They'll hate me for saying that, because they'll get tons of phone calls, but they're a very solid partner. I couldn't wish for better, really. They stood by me through thick and thin, because it was a difficult project, and I could make some stumbles, creatively, in learning to work with editors properly and all that sort of thing. But they were solid and said, "Keep going, Steve. Hang in there. It'll get done. Don't worry." They've been very supportive.

"There was no pressure to say, 'Hey, you got into Sundance. You have to take them up on that opportunity.' They were like, 'If you really have concerns....'"

NFS: Was there a rush to get the film completed for Sundance? After working on the film for so many years, what were those final weeks like?

Loveridge: It was 90% in the can, but when we were packaging it up to send it to Sundance, I suddenly had these crippling doubts about some of it. I had a massive doubt about the film overall, "Oh, my God, are people just going to laugh at this, a cut-and-paste assembly of old videotapes. Is it even a film?"

In a more specific way, there were a few shots in the film that wasn't originally, and a few that were in the film that I had a really good talk through (and a lot of debate) with the editors and with our producer, Lori Cheatle, about what had made the cut, and what hadn't, and why. I think that was really helpful to have the space to have a good hearty discussion with minutes to spare, "If we really decide that this isn't ready, then we'll say it's not ready, and we'll pull it."

There was no pressure to say, "Hey, you got into Sundance. You have to take them up on that opportunity." They were like, "If you really have concerns...." Actually, I was pleased with the film that we were presenting. We made a few last minute changes, but it's so near to what I set out to do when I came with an idea of the subject and the things that I wanted to explore, and the kind of style of film that I wanted it to be. It felt pretty close to that, and that's as much as you can hope for, I think.

NFS: As a filmmaker, what are the main things you took away from your first time directing a feature?

Loveridge: With me, it's always been a confidence thing, learning to push the decisions that you've made internally and getting somebody to just do what you're telling them to do. I found that very difficult at the beginning of this process. I would sit and watch edits, where I'm like, "I've asked for that shot to be changed, and you haven't changed it," and so I had obviously lost that argument. Should I let it slide and then wrestle with things later?

I'm now just a lot more confident and direct in the people that I work with, because it's a lot easier than getting in that passive-aggressive way of whining on about things and asking somebody else to tell the editor (on your behalf) to change this thing because you can't get it done. I think I'm a lot more direct in my relationships with the people I'm working with now, and I've learned to be like that because it's a lot easier on everybody if you're straight up, honest, and forthright about what's really important to you.