'Searching': How the Sundance Digital Thriller Reinvented Filmmaking on a Computer Screen

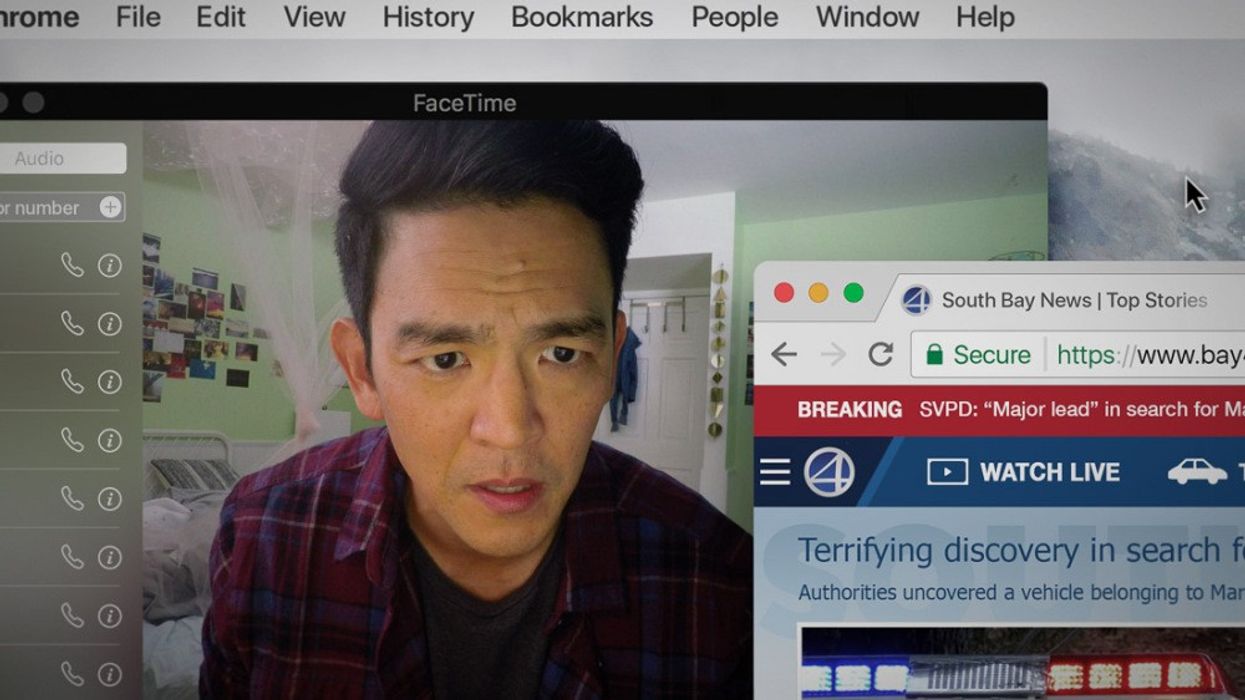

In Aneesh Chaganty's thrilling mystery 'Searching,' starring John Cho, the action takes place entirely within a computer screen.

At film festivals, it's easy to hyperbolize. Among the many accolades tossed around is the word "reinvention": so-and-so reinvented the thriller with a twisty, logic-defying screenplay; such-and-such reinvented cinematography with sweeping, gravity-defying drone shots. But at Sundance this year, only Aneesh Chaganty's film can claim to have reinvented filmmaking.

Chaganty, a first-time filmmaker, and his co-writer and producer, Sev Ohanian, have crafted an emotionally resonant and thoroughly gripping thriller set entirely on a computer screen. Searching stars John Cho as a father who, after his daughter goes missing, desperately tries to find her by turning over every stone imaginable—and previously unimaginable to him—on her computer. When combing through her Instagram and hacking his way into her Facebook account proves less than fruitful, Cho stumbles across a self-streaming site called YouCast, which will ultimately lead him deeper into the labyrinth that is the internet—and, accordingly, the teenage mind.

The nail-biting action unfolds on various screen elements such as FaceTime, text messages, YouTube clips, desktop navigation, and even a GPS app. It's so engrossing and all-consuming that when the screen goes blank in a pivotal moment, leaving only the Apple "flurry" screensaver suspended in a void, we feel disembodied, robbed of agency, and utterly alone—not unlike how Cho's character feels throughout the entire movie.

Chaganty and Ohanian's story is cleverly laden with red herrings and shocking revelations, but it only works because it has been infused with genuine humanity. The film's opening sequence rivals Up with its ability to take the audience on an emotional journey before the film has even truly begun. Even more than a character-driven thriller, Searching is an anthropological study of human behavior with technology. On screen, Cho's character wordlessly considers the subtleties of texting an exclamation point or a period. He types out a long, explosive text message, only to delete it and send something shorter and more rational. He is constantly multi-tasking: texting while in meetings, FaceTiming while surfing the internet. But for all the undeniable power of the electronic universe, how much do our computers truly know about us?

No Film School sat down with Chaganty and Ohanian to discuss how they co-opted computer technology to direct cinematic attention and why they felt compelled to rename their editors "Directors of Screen Photography." Searchingis in theaters this Friday, August 24th.

No Film School: You guys have had an incredible Sundance. A $5 million deal from Fox Searchlight is what most first-time filmmakers dream of. And it was one of the first deals out of the festival this year!

Sev Ohanian: Yeah, it's been crazy. I think I've felt every single emotion you could possibly feel in the past couple days.

Aneesh Chaganty: We are so excited about it. I can't wait for people to see this thing. We've worked so hard on it.

NFS: How did the deal go down?

Chaganty: We went to the premiere party and then right afterward we got dragged away and had to deal with all the business things. That was my first time going through this because it was my first movie. By 6:30 AM, we had a deal and that was that, and now people are going to see this movie soon.

Ohanian: I've been a producer on a bunch of indie films, starting with Blue Bell Station, which was here at Sundance in 2013, and a few others, so I had been through that all-night process of meeting with distributors and fielding offers. I think we were as prepared as we could possibly be for something that you can never be prepared for.

NFS: How did you two conceive of the idea of making an entirely screen-based movie in the first place?

Ohanian: Aneesh and I met at USC film school. I was his TA in a class and he was a student. We committed to working together as writing partners: I would produce for him and he directed. We had this awesome opportunity early on where Google had reached out to a number of film schools to find people who would create content using their Google Glass technology. They were trying to sell the Google Glass as a viable device for filmmakers to use to make movies—which, by the way, it's not at all. They wanted me to help create a technical video that would demonstrate how it could be used for filmmaking. Of course, the only person I thought to bring on was Aneesh to come and direct it.

We realized pretty soon that nobody liked Google Glass, but more importantly, that there wasn't any marketing or any commercials related to it. So, we thought immediately, "Why are we taking this opportunity to make a technical demo when we can instead make something that Google would like? Why don't we make a story—something emotional?" We came up with an idea that involved me wearing the Google Glass and then spending the entire production budget—the small percentage we had—on flying me to India and shooting a video as I traveled. It was a very small project—two and a half minutes long.

We put it on YouTube and it exploded overnight. It got two million hits in the first two days and a million hits overnight. By that weekend, Google had given me a call saying, "Hey, do you want to come up to New York and write and direct a commercial for us?" So, that went on for two years—developing, writing, and directing commercials for Google.

Ohanian: Then, the opportunity to work on this film came up. Aneesh and I were looking for a screenplay that we could write for him to direct and for me to produce. I had a general meeting with Timur Bekmambetov's mom and pop company, called Bazelevs. They just made a movie called Unfriended, which had a very successful commercial release, and they were very interested in making more content that would take place in computer screens. They asked me if I knew anybody I could bring in to help direct a short film that would be a computer screen movie and, of course, I thought of my creative partner, Aneesh. Aneesh and I got together and pitched them a short film—basically Searching as an eight-minute script.

They called us in to have a meeting about that short and the first thing they said was that they didn't want us to make the short. It was kind of a bummer. But instead, they said, "We'd rather make this into a feature that Sev can produce, Aneesh can direct, and you guys can write the script together. We'll finance it." and Aneesh's response was...

Chaganty: I said no. And I could see the heat sort of radiating from Sev's side.

Ohanian: I'm like, dude, this is independent filmmaking. Nobody gets first-time director features completely financed. No directors ever say no to that.

NFS: Why did you say no, Aneesh?

Chaganty: Well, in the moment, it felt like I would be taking a concept that worked really well for seven minutes and then stretching it into something that would feel more like a gimmick. I did not want to make a first movie that took place in a computer screen. It just didn't feel like a natural story. It felt like there were more corporate reasons for it than there were emotional or character reasons, and that was the reason that I said no in the first place.

"Our goal with the opening scene was that by the time the audience has seen the first 10 minutes, they've forgotten that they're watching a story that takes place on a computer screen. "

But as we were leaving, Sev was like, "Look, we'll be in touch." So, we took the opportunity seriously. We kept thinking about an angle. A few weeks later, I was back in New York City and I texted Sev, "Hey, I've got an idea for an opening scene," and he was like, "I do too—you want to jump on a call?" We pitched each other the exact same opening scene.

NFS: Yes! I love that opening scene. I'm sure people have told you it reminds them of Up in terms of how much emotional foundation you lay in such a short period of time.

Chaganty: Yeah! We basically pitched each other that scene, almost beat for beat, the identical version. All of a sudden we had not just a gimmick but something that felt like it was a commentary. But most importantly, it was character-based, it was thrilling, it was emotional, and most of all, it was cinematic.

Ohanian: Our goal with the opening scene was that by the time the audience has seen the first 10 minutes of the movie, they pretty much have forgotten that they're watching a story that takes place on a computer screen. We wanted them to get lost in the story and the characters and just be fully on board no matter what happened next.

Chaganty: I quit my job at Google, moved back to LA, and started working on [Searching].

NFS: What was the process of co-writing the rest of the film?

Ohanian: Aneesh and I work really well together. I'd probably characterize our writing style as two friends having a lot of conversation, sharing a lot of jokes, and having a lot of arguments over many, many weeks, and then finally putting all of that work onto the page. But writing this movie was especially difficult because there's no book you can buy that teaches you how to write a movie that takes place on a computer screen.

Chaganty: Yeah. We couldn't write it like a traditional screenplay: INTERIOR: GOOGLE CHROME - FACEBOOK NEWSFEED - NIGHT. Immediately we had the challenge of, "How the hell are we going to write this thing?" Within the first few days of writing, we were just talking about how it was even going to be presented.

Chaganty: We ended up with what we called a "scriptment," which is sort of just a hybrid between a treatment and a script that had every line of dialogue and every line of text but was readable. All the texts were presented how they were presented onscreen. If someone typed something and backspaced it, it would be crossed off. It was a playful presentation, but it was able to convey the entire story.

Every single department in this film has to relearn their job to pull off this movie, and that goes for the writing, too.

NFS: How, specifically, did each department have to relearn its job?

Chaganty: Without a doubt, the first and foremost department that had to relearn their job were the editors. Their job so exceeded the traditional bounds of "editing" that we actually created another title for them: Directors of Screen Photography.

Speaker 3: Oh, wow. I love that.

Chaganty: It was absolutely deserved. In a traditional film, an editor edits for about four months—they get all the footage from production, and then they start cutting it up. In this movie, they started editing the movie seven weeks before we even shot a frame.

There are two cameras in the film, essentially. There are the cameras with which we shoot all the footage that's presented in the world of the movie, like Skype calls or news footage. Then there's the camera that we, the movie, are looking at everything through. To understand how those two play with each other, we needed to treat this movie like a Pixar movie and make it animatic.

We also needed to be able to communicate with the actors what the hell they were doing on set. So we made this hour-and-forty-minute version, which, by the way, just stars me in every single role. I was the dad, the daughter, every friend, the detective. We showed that on set to the cast—especially John because he's usually the one operating the computers. It was important that he knew exactly at what line or when and where to press buttons.

"Even though it takes place on a computer screen, it doesn't mean that it can't be cinematic and engaging."

Then, we took all that footage and put it back into the animatics and continued to work on it. So, the editor's job was not only starting from scratch but also capturing the footage, framing the footage, then eventually graphic designing the images, animating the images, adding camera shakes, etc. In the end, it took about a year and a half just to edit this film. And that's just the editing! It was a crazy amount of work that we put into the film.

NFS: You were talking a little bit about animating the screen. One of the most ingenious parts of this film, I thought, was that it invented an entirely new way to direct audience attention. I was paying attention to the way you moved the cursor around the screen and the main character highlighted or copy-pasted text. How did you build out that visual language and make it cinematic?

Ohanian: It has to go back to the animatic work that we decided to do before we started shooting. We didn't want the film to feel accidental; we wanted the final product to have a lot of direction as far as where actors are at what point in the screen.

Our whole point was that even though it takes place on a computer screen, it doesn't mean that it can't be cinematic and engaging. We knew that that was going to be one of the variables that would allow the characters in the story to shine. The camera work had to serve [the characters] rather than just being there to serve the purpose showing a movie on a computer screen.

Chaganty: Yeah and to add to that point, as far as, directing peoples attention goes, the objective here was to constantly find different ways of doing that. At the end of the day, that's what this film is. Because it takes place on a computer screen, our objective is to constantly be able to present information in a way that is not boring or repetitive.

NFS: When it came to the mechanics of writing the plot, how did you create that sense of suspense and upending audience expectations? In the end, as you said, it's not just the device that you used to tell the story that's engaging here; it's the story itself.

Ohanian: As we were putting together the first outline, we were exploring all the things that we do on our computers every day: the text messages we send, the FaceTime videos, the emails that we're waiting for, how we're navigating to get somewhere. Then, we tried to isolate all of the emotions that happen during those moments. I think we've all been there when a person is texting you something but it's taking forever, and that sense of anxiety builds, or when you type out a long text and you have to delete it.

We found all those moments and we made sure to incorporate them into our script in a very organic way so that when the traditional mystery twists and turns are happening—because it's happening through this device that we all spend our lives on every day—it's more relatable and more grounded.

"We encountered major setbacks nearly every day of making this movie, especially in the editing."

It came with a lot of research. We studied a lot of mystery films to see how scenes work. But the important thing for this movie is if it were not taking place on screen, the story would still hold emotional merit. Our objective was finding the story first and then adapting it into something that takes place on our computers.

NFS: Can you take me through a day of production? I'm trying to visualize how, exactly, you shot, for example, a scene on FaceTime. Were you using a FaceTime camera?

Chaganty: I mentioned earlier that we had the animatic to use as a guide for eye line. For every FaceTime shot, we used a GoPro to shoot it. We had a camera rigged that was basically a GoPro strapped on top of a black laptop that John or Debra would be acting against. I would occasionally open up the animatic to show them their eye lines. When they were talking to each other, we had them in two separate rooms of a large house that we shot in, and they could only see each other on this small screen window.

That proved to be an extremely difficult acting challenge for both of them because it's unlike anything that anybody has done before. When doing their lines, they had to muster up as much emotion as they could to act against, essentially, nothing. Then, they had to learn how to behave in front of a "computer screen" camera.

NFS: I'm sure that you probably had to adjust the way you gave direction to actors looking at a screen because it's a completely different configuration.

Chaganty: Totally. In a regular movie, when you frame up a shot, you sort of tell an actor on a left to right basis, these are the edges of your frames. You say, "You can move within this, but don't move outside of that." And you never want an actor moving forward or backward because your focus is pulled at a specific time.

"We had a camera rigged that was basically a GoPro strapped on top of a black laptop that John or Debra would be acting against."

Early on in the film, shooting with a GoPro, we realized that because of the wide angle lens, one of the things that translated well was moving forward and backward. One of the things that didn't translate at all was moving side to side. So if I ever wanted John to take a beat between lines, I would be like, "Move backward or move forward." You can feel a change.

NFS: Was there any point in the process where either of you encountered setbacks that made you wonder how you were going to pull this off? How did you circumnavigate it?

Chaganty: We encountered major setbacks nearly every day of making this movie, especially editing. The process that our editors had invented was something that had never been done before—and certainly not on the consumer-grade computers that we were using.

The camera could be put together on two computers that you could find in any high school student's bedroom; as a result, most movies on their editing timeline have maybe two layers of video. We had 37. So, every 10 minutes, our computers would be crashing. It kind of felt like we had gone back in time and we were editing on an ancient editing software because everything took so long. We always had to keep our focus, keep ourselves grounded, and not lose sight of the forest for the trees.

Ohanian: It took a while. We're never doing this again.

NFS: If someone came up to you and said, "Look, I want to make a 'computer screen' movie. What are the most important things I should know before I set out to do it?" What would you tell them?

Chaganty: I would say make sure your intentions are clear. At the end of the day, this is a film that's going to be defined by its context. Yes, it's a good story, but there's no escaping the fact that this is a movie that takes place on a computer screen. So, to do it again is to try to put yourself up against this movie, and against the one before it. Just say make sure that if you want to take the mantle—and you're more than welcome to it—that you're trying to contribute in a new way.

NFS: And what about from a producing perspective?

Ohanian: Oh, man! Double your budget and schedule because it's going to cost a lot more and take a lot more time than you think. I promise that.

Also, this is one of the movies that would just not have been possible had it not been for a family-style group of people who came together and worked far too long and far too hard. It was one of those projects that had no end in sight.

Chaganty: Yeah. It was always increasing; there was always something else we had to do.

Ohanian: I've made a lot of indie films as a producer, and usually you kind of know how it will go: a couple of months of prep, a month of shooting, three months of editing, a month of wrapping up post, and you've got your premiere. For us, it was the exact opposite of that. I mean, there were moments where we were editing and it was just me, Aneesh, our fellow producer Natalie Qasabian, and her two editors, Will Merrick and Nick Johnson, and we literally had no clue what year this film would be completed in. I think the fact that we all kept chugging along is a huge testament to that team—the ability to stay together through that.

For more, see our ongoing list of coverage of the 2018 Sundance Film Festival.

For more information on 'Searching,' click here.

"'Back Home"via Mercedes Arutro

"'Back Home"via Mercedes Arutro 'Back Home'via Mercedes Arutro

'Back Home'via Mercedes Arutro